Long overdue statue of Joe Frazier a sign of love from Philadelphia

It always seemed strange that the Philadelphia chose to exhibit a statue of a celluloid heavyweight champion and overlooked one of its own who had been an authentic one. But for years that remained the unaddressed status quo. At the steps of the Philadelphia Museum of Art stood a sculpture of Rocky Balboa, the cartoonish lug played by Sylvester Stallone in the Rocky series. And yet there was no such acknowledgement in any public space of Joe Frazier, whose rivalry with Muhammad Ali in the 1970s produced a pugilistic trilogy for the ages. Go figure.

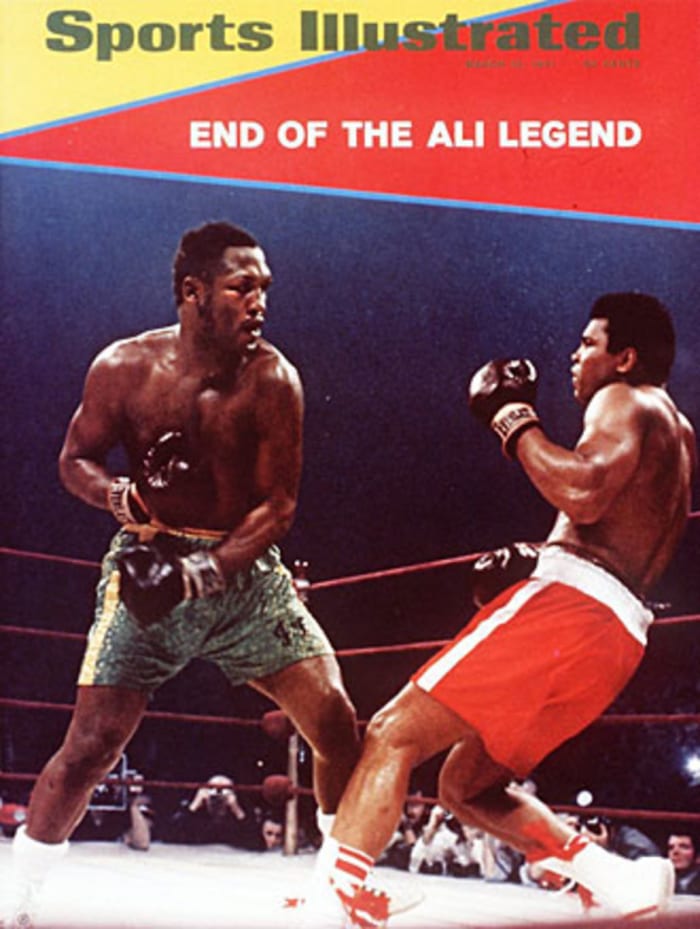

That omission is on the verge of being corrected. In a ceremony Saturday at XFINITY LIVE in the South Philadelphia Sports Complex, there will be an unveiling of a statue in commemoration of the legendary Smokin’ Joe, who died in November 2011 of liver cancer at the age of 67. Artistically, Philadelphia sculptor Stephen Layne has produced a compelling piece of work. It stands 11 feet tall, tips the scales at 1,800 pounds and seals in bronze a depiction of Frazier at the apex of his career: that very instant he floored Ali with a left hook in 15th round of “The Fight of the Century” in March, 1971.

Joe, it was worth the wait.

Seeing it for the first time brought tears to the eyes of Joe Hand, the former Philadelphia cop who befriended Frazier as one of the original investors in Cloverlay, the consortium of local businessman that joined together in 1965 to lend the then Olympic champion financial support. Of the long held belief that the son of a South Carolina sharecropper had been underappreciated in his hometown, Hand announced at a City Hall tribute in honor of Frazier in 2012 that he would get a statue built even if he had to fund it himself. “I figured it would cost a couple of hundred thousand dollars,” says Hand. “And I was willing to come up with that if necessary.”

SI 60: 'Lawdy, Lawdy, He's Great'

He did not have to. As word spread that the effort to build a statue was underway, others stepped forward with cash. According to Philadelphia attorney Richard Hayden, who presided over the budget for the project, the sum in contributions came to approximately $180,000. The donors included his client, the XFINITTY LIVE developer Reed Cordish, at a total of $90,000 (which included $20,000 for the base), followed by Hand and his son Joe Jr. at $30,000, and both former middleweight champion Bernard Hopkins and billionaire Jerry Perenchio at $25,000 apiece. Perenchio, who promoted Ali-Frazier I at Madison Square Garden, also gave permission to replay The Fight of the Century for a fundraiser that netted an additional $15,000. The statue will occupy the corner of 11th Street and Pattison Avenue and become part of the City of Philadelphia public art collection.

"Joe Hand and his son Joe Jr. were the ones who picked up the ball and ran with it," says Hayden, who worked closely with the Frazier family. "At that point I heard from Mayor (Michael) Nutter, who asked if our client was interested in being involved. I called him and he said, ‘We’re in.’ So then we had to line up an artist."

Originally, the artist that was selected for the job was Larry Nowlan, who had done the sculpture of Hall of Fame Phillies announcer Harry Kalas that stands at Citizens Bank Park. But Nowlan died suddenly only a few months into the Frazier project and Layne was appointed to take over. Cooped up in his studio in the Fishtown section of Philadelphia for two years, he labored on the project with the same pounding fury with which Frazier smothered his opponents. He worked six hours a day, six days a week.

Ruben Amaro's dismissal as GM end of Phillies' days as family business

Slowly, the concept he envisioned revealed itself. Working from old photographs of Frazier, Layne welded pipes in place to form the skeletal substructure, which he then covered with cut-up pieces of foam. Over that Layne layered on 400 pounds of clay, beginning with the head and working his way down the body. With a wooden tool in his hand, he circled the piece again and again with an appraising eye in search of areas that commanded revision. At one point early on he had to give Frazier a shave.

"Joe was unshaven in a few of the photographs I had seen, so I presented him that way because it seemed to help structure his face," says Layne, 47. "But I received a long and very kind email from (the late Philadelphia Daily News sports columnist) Stan Hochman, who said he loved what I was doing but that Madison Square Garden had a no facial hair rule back in the early 1970s. Sure enough, I looked at video of The Fight of Century again and Joe was clean-shaven. So I had to go back and remove the beard."

However powerful the sculpture had been in the studio, the effect is even more striking now that it has been cast in bronze and polished. Layne has imbued it with a thrilling dual energy: There is Frazier, chin anchored in an attitude of focused aggression, and yet his eyes up and in a place beyond his fallen opponent, fixed upon what Layne characterizes as “that instant moment of achievement.” Hayden says, “It is almost as if the piece is in motion. You almost have the feeling that Joe is flying across the canvas at you.”

Layne had hoped to encourage that impression.

Even when Frazier won the heavyweight title in 1971, the bigger news was that Muhammad Ali had lost.

Tony Triolo for Sports Illustrated

"You are dealing with a static object, yet are trying to express movement," says Layne. "There is a quote by Rodin that says you do that in three phases: Where you were, where you are and where you are going. With the placement of his legs and feet (in the past), his torso and hands (the present) and finally his neck and head (the future), the intention has been to create that flow of movement."

So what would Joe think of it?

"He would have looked at it and asked: All of this for me?" says his daughter Weatta Frazier-Collins, who adds that the grandeur of the sculpture far exceeded her expectation. "He would have said, 'Spend the money on a youth learning center or a playground.'"

But even so Joe would have been delighted. Although his relationship with Philadelphia had been a long and cordial one, it hurt him that there had been no public recognition of his place in sports history, especially in a city where there are statues of other sports legends like Wilt Chamberlain and Mike Schmidt. “Joe appreciated it when people showed they appreciated him,” said Les Wolff, his former businessman manager. But Joe Hand Jr. says that when you are the star athlete in an organization, “generally the team will push for you to get recognition. As a boxer, Joe had no one until my father stood up and said: ‘Enough of this!’”

And Joe Hand Sr. could not be more pleased. "I can cross this off my bucket list now," he says with a certain pride in his voice. "This has been a long time coming."

Mark Kram, Jr.’s father covered all three of Joe Frazier’s fights with Muhammad Ali for Sports Illustrated. He recently published a collection of his dad’s magazine pieces, “Great Men Die Twice: The Selection Works of Mark Kram.” Kram Jr. was also the recipient of the 2013 PEN/ESPN Award for Literary Sports Writing for his book, Like Any Normal Day: A Story of Devotion.