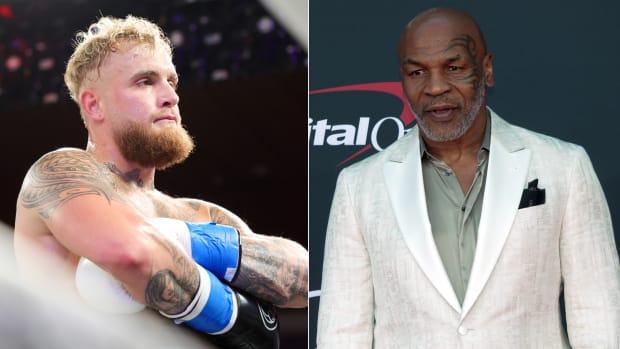

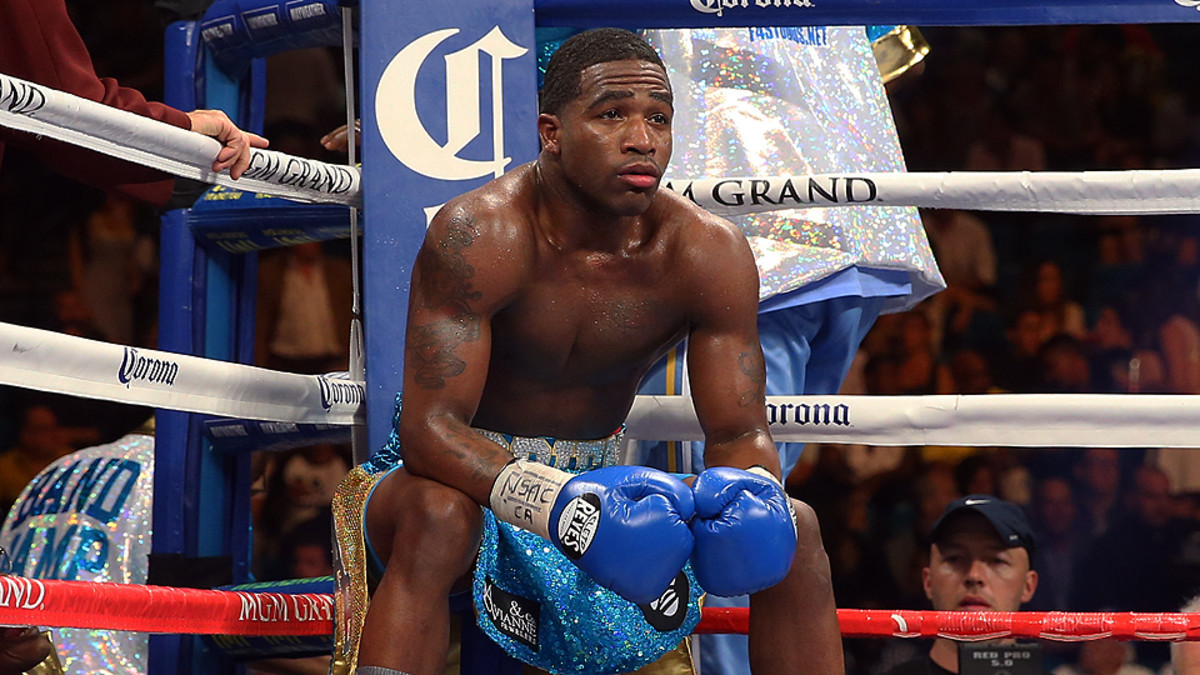

As Adrien Broner prepares for his next title fight, maturity issues remain

Adrien Broner is fighting this weekend, and if you didn’t know, no one would blame you. Besides facing an unheralded opponent (Khabib Allakhverdiev) for a completely undeserved title (the WBA’s 140-pound belt), Broner has vowed to do nothing to promote the fight, a reaction to the backlash towards him for receiving a world title shot four months removed from a lopsided loss to Shawn Porter.

“I will only talk after my fight from here on out,” Broner tweeted. “No more press conferences. No NOTHING!”

True to his word, Broner has gone radio silent. He dispatched an assistant to the podium at an August press conference to speak for him and, save for a handful of tweets and Instagram posts, has acted like his showdown with Allakhverdiev doesn’t exist. It’s a childish tantrum that undoubtedly has infuriated executives at Showtime, which is putting up a seven-figure license fee for the right to air the fight, and the few levelheaded members of Broner’s team, who desperately want to halt Broner’s self-destructive free fall.

And that’s what it is, really. Two years ago Broner was one of the brightest young stars in boxing, an heir apparent to Floyd Mayweather. That was before Marcos Maidana dropped him twice in a rout in 2013. That was before Porter bullied him en route to an easy decision win. Suddenly, Broner’s immaturity outside the ring—the alcohol-infused incidents, the brushes with the law—no longer burnished his bad boy image, but became warning signs of an unstable athlete.

Funny thing is, there is great depth to Broner. I spent a week with him in Colorado Springs in 2013, before his loss to Maidana. In the quiet of a dressing room, Broner was introspective. He talked about the challenges of growing up in English Woods, a since-demolished cluster of subsidized housing projects in north Cincinnati. His voice lowered when he opened up about the beatings he took in his early days in the gym and the perseverance it took to keep going back, to succeed when surrounded by so much failure.

It’s a side of Broner rarely seen. Instead, Broner is perceived as childish and spoiled, as a fighter who doesn’t take his career seriously. It’s a perception that, frankly, is also accurate. I’ve observed many training camps, including those of Floyd Mayweather, Manny Pacquiao, Gennady Golovkin, Danny Garcia and Lamont Peterson. Broner’s was by far the most disorganized. Training was paused for Broner to watch DVD’s of his knockouts playing on a screen above the ring. For most fighters, sparring is regimented. Several fresh fighters alternate in and out over three- or four-minute rounds in order to maximize its effectiveness. Broner’s was different. Before the Maidana fight, Broner sparred with Hank Lundy. The sessions were two 18-minute rounds that were less a test of skills than a war of attrition. Broner and Lundy hurled insults at each other and sharp sparring quickly, and predictably, devolved into a sloppy wrestling match that did little to prepare Broner for the pressure Maidana would apply weeks later.

The Legacy: At 73, Muhammad Ali remains an inspirational force

, Keith Thurman and Amir Khan.

Some changes could help. Mike Stafford, Broner’s longtime trainer who groomed Broner since childhood, has done an excellent job building Broner into a world champion. But Broner’s most recent losses lacked any discernible game plan. Perhaps Broner would benefit from supplementing Stafford with a more accomplished pro coach, much like Chris Algieri, who added John David Jackson to his team to work alongside Tim Lane, and Deontay Wilder, who teamed Mark Breland with Jay Deas, have done. Think of what an offensive oriented trainer like Jackson, Freddie Roach or Abel Sanchez could do with the fast hands and concussive power of Broner.

Of course, Broner has to decide to take his career seriously first. That means no more ballooning in weight in between fights, it means cutting back on his publicly outlandish lifestyle, it means preparing to be a champion like a champion. The greatest fighters of this generation—Mayweather, Golovkin, Andre Ward, Miguel Cotto—share one characteristic: discipline. They are singularly focused on success, evidenced by their training and unparalleled preparation. If Broner complements his talent with that work ethic, he will succeed. If not, it won’t be long before his once rising star becomes a cautionary tale.