Tar Heels Excited to Potentially See Themselves in NCAA Football Video Game

Make no mistake — the NCAA didn’t vote to allow athletes to profit from their name, image and likeness on Tuesday, but for the first time, it did acknowledge that it will inevitably have to embrace change under pressure from state legislatures.

"There’s no question the legislative efforts in Congress and various states has been a catalyst to change," NCAA President Mark Emmert said. "It’s clear that schools and the presidents are listening and have heard loud and clear that everyone agrees this is an area that needs to be addressed."

California was the first state to clear the way for college athletes to profit from their name, image and likeness, while numerous others have introduced similar bills while North Carolina Republican Rep. Mark Walker is championing one in Congress.

While it’s nice to see, it’s a bit too early for North Carolina athletes to get excited.

“It’s exciting to hear,” receiver Beau Corrales said. “I don’t know how accurate their plan to put it into action is, so I’m not too worried about it or anything like that, but it’s definitely good news to hear. It’s kind of just stuff moving in the right direction; everybody’s got to start somewhere so I’m excited for it.”

There’s much to work out, like how and when the rules might be implemented, along with what influence that compensation can have in recruiting plus myriad of other details that the NCAA’s working group will be charged with determining.

Regardless of the other details, one stands above the rest for many players.

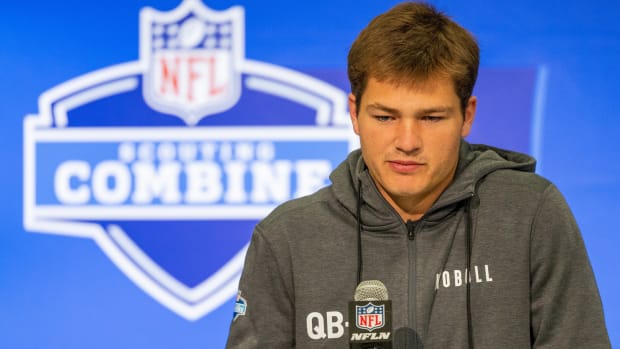

“That’s really the only thing I want back, is the video game,” Carolina quarterback Sam Howell said, smiling.

The video game in question is EA Sports’ NCAA Football series, which began in 1993 as Bill Walsh College Football before transitioning in 1997 with the release of NCAA Football 98, featuring Heisman Trophy winner Danny Wuerffel on the cover.

Every summer, the game’s release signaled the start of a new season, with fans quickly developing online communities that created accurate rosters for the game, replacing the generic numbers that appeared in the factory version of the game.

For young players with Division I aspirations, there were also dreams of one day seeing themselves featured in NCAA Football and having the chance to play as themselves.

“Oh, shoot, I had a whole freakin’ roster of my Pop Warner team on the NCAA game whenever I had it,” Corrales said. “I think that just goes to speak on how much little kids look up to that. It’s definitely exciting and brings back memories, so definitely some nostalgia with that, and I’m sure a lot of other people feel that.”

Carolina safety Myles Dorn went with Heisman winner Reggie Bush — a 99 overall rating — when he played NCAA 06. Corrales, who grew up minutes from the University of Texas, had the nerve to bench Vince Young in favor of his created player.

“Vince was on the bench whenever I was in, because I was playing quarterback back then,” he said.

With apologies to Carolina fans, Howell admitted he played with Duke and quarterback Anthony Boone, who he’s grown close with since the two started training together when he was a freshman in high school.

“That was my guy, so I played with him,” he said.

The game was ultimately discontinued after NCAA 14 released in the summer of 2013 as pressure mounted regarding name, image and likeness rights and EA Sports was forced to pay a $60 million settlement to players who had been featured in the game by number, appearance, skill and position.

It remains so popular that fans of the series continue updating rosters annually for the final release.

Dorn certainly won’t see himself in a game as this is his final season at Carolina. There’s a chance things could be worked out for Corrales to see himself featured as a senior, while Howell will have a few years to hope for a resolution.

As for Corrales’ catch rating in the hypothetical NCAA Football 21, he’s still got a few games to figure that out.

“Ask me that at the end of the season,” he said.

Whenever it happens, not only will players who grew up dreaming of seeing their virtual-self playing for a virtual-national title against their real-life friends, but it will also come with a real nice paycheck.

That’s better than having your created recruit win the Heisman on their way to a national title at Idaho.

“I think it’s big just for up-and-coming athletes to be able to use their name and use themselves and be able to do whatever they want with it,” Dorn said. “Just to have ownership of whatever they decide to put out to the world.”