Inspiration to all

B-Rad, B-Rad, B-Rad.

Suddenly, Brad Hennefer rises off the Cherry Hill East High bench, slings off his red-and-white sweats, and checks in at the scorer's table.

Play resumes and the ball quickly reaches Hennefer's hands. The opposing players clear a path, so Hennefer can drive in for an uncontested layup, which he misses, but then scores off the rebound. A huge roar erupts from the crowd, some fighting back tears.

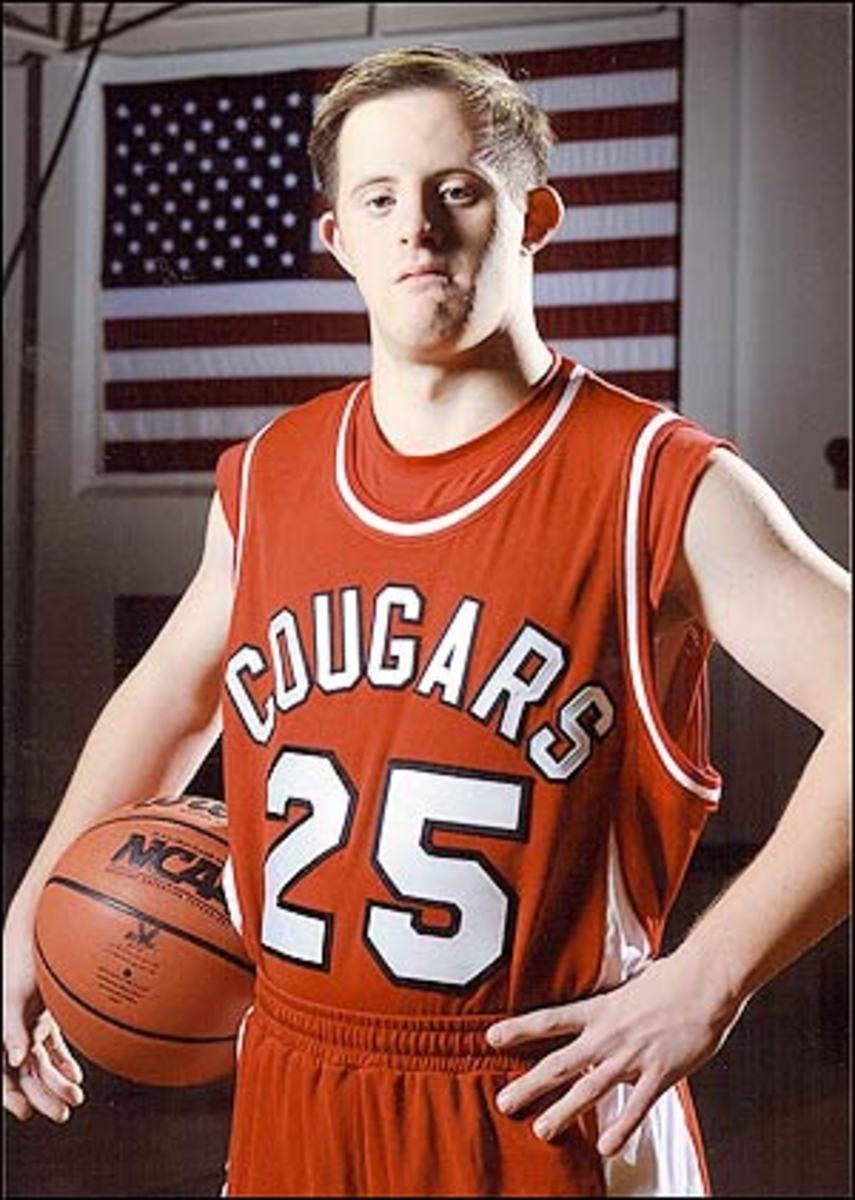

It's a scenario that has played out time and time again this season at Cherry Hill East. Hennefer, a 5-foot-10 senior, was born with Down syndrome, a cognitive disability that causes delays in the way a child develops, and often leads to mental retardation. That hasn't deterred Hennefer, 19, who has played in 21 regular-season games and scored in eight for the Cougars this season. He has 23 points, including a three-pointer with 26 seconds left in a game against Lenape (N.J.) last Thursday. Cherry Hill East was down by six at the time, and after Hennefer's big three the Lenape coach told his players, "[Hennefer is] not to touch the ball [again]."

Hennefer is believed to be the only high school varsity basketball player in the nation with Down syndrome, according to his coaches. But above all else, Hennefer, also an excellent golfer, is a joy to be around. His presence has affected teammates, classmates, family, friends and opposing teams and their coaches, who have an understanding that when Hennefer enters the game, they let him shoot.

Mention his name to anyone who's ever met Hennefer or seen him play and a smile usually follows. Cherry Hill East coach John Valore, the dean of high school hoops coaches in South Jersey, has seen it all. He's 63 and has been the head coach of the Cougars since 1976. It's to a point where Valore is now coaching the children of players he once coached in the 1970s and '80s. But Valore has never had a player like Hennefer.

When Hennefer first thought about playing basketball his freshman year, Valore was slightly apprehensive. He thought about using Hennefer as the team statistician.

"Then I thought about giving him a chance to play, and thought it would work out nicely, which it has," Valore said. "I wanted to see where it went, and four years later, Brad is going to get a varsity letter for basketball. There's been such a positive reaction to this. He really has a way with people, and how he touches people. But I also have to say, Brad didn't get any breaks. I'll get on him just like I do any of my other players. Brad goes through all of our drills, and the more he understands a drill, the better he is at it. He works with the team on offense and defense. And we have used him in some key moments, like the game against Lenape."

If anyone was apprehensive, it was Bob Hennefer Sr., Brad's father. "I didn't want another kid cut to create a roster spot for Brad," he said. "Brad used to come home every night and say, 'I hope I don't get cut, I hope I don't cut.' I never had a concern whether or not he was cut. If they couldn't add a roster spot, I didn't want Brad taking another kid's place who could have been more deserving to make the team. I wouldn't have minded at all if Brad was the team manager. All I wanted was him to be around and be a part of the team."

After tryouts for the freshman team, Valore told the Hennefers they were giving Brad a uniform. But this came after Cherry Hill East petitioned the Olympic Conference, the league the Cougars play in, for an additional roster spot, which the conference agreed to.

Drew Berlinsky, the Cougars' starting senior shooting guard, struck up an immediate friendship with Hennefer the first day they met as freshmen. Berlinsky held no preconceived ideas about Hennefer.

"Brad is pretty unbelievable," Berlinsky said. "I know people can be cruel, but Brad carries himself in such a respectful and mature way, he never really faces that kind of stuff, at least not here. Brad is probably the most popular kid in the school."

Hennefer, sitting next to Berlinsky, hears this and smiles. He's an accomplished public speaker, once delivering an address to thousands at the national Down syndrome conference. He is also the New Jersey Special Olympics golf champion and helps his father coach young players with cognitive disabilities.

"The attention I get does make me happy, it does," Hennefer said. "I hear the crowd when I come into games and I don't get nervous like I used to. I played golf growing up, but I like basketball because I get to be with my teammates. Drew is like a brother to me. Coach let's me in the fourth quarter and I shoot. But I think I'll remember my senior year here and making the best friends ever. I'll miss the guys when they go off to college. I'll remember these guys for the rest of my life."

The Hennefers found out Brad had Down syndrome the day he was born. They opted to take a different approach, however, than some parents with handicapped children.

"We knew instantly we wouldn't treat Brad any differently than his older brother [Bob Jr.]," said Nancy, Brad's mother. "But it hasn't been easy, from the outside. We've spent the last 19 years breaking down barriers. Brad was the first enrolled in a private preschool, and that was a struggle. But when we started in the Cherry Hill School District, where they normally didn't start children with Down syndrome in mainstream classes, they placed them in segregated classes. It took a lot of negotiating and convincing to get Brad into the mainstream. But I do have to say, the Cherry Hill School District has been great with Brad. We're happy things worked out the way they did."

The Hennefers themselves also prepared Brad. Much of his educational foundation came from home, because the Hennefers didn't want to force Brad on the school system and expect the system to educate and care for him. "That had to start with us, in our home," Nancy said.

Part of Brad's socialization training involved sports. The Hennefers exposed him to everything, from skiing, skating, swimming, tennis and bowling, to golf, a sport their son Bob Jr., 23, is well versed in, as the local PGA pro at Woodcrest Country Club, in Cherry Hill.

Basketball came in Brad's freshman year -- almost out of the blue. He received little playing time then. After his freshman season, Brad was awarded a framed jersey, which now hangs on his bedroom wall, surrounded by his three varsity golf letters. Soon he will add a varsity basketball letter.

"It's been a very enriching experience for me, and for everyone who comes in contact with Brad," Valore said. "I think it comes from an understanding as to how hard Brad's worked through this. It's made me a more understanding person, because it's the first opportunity I've had in this situation. Working with Brad, it's enlightened this team and me immensely how a young man can work and overcome adversity. Brad makes everyone around all better people, whether it's during practice or during a game. It is true love."