Hollywood Beginning

After five weeks honing pickoff plays, relay throws and bunt coverages, Dodgers first baseman James Loney and shortstop Chin-Lung Hu attended to one final piece of spring training business. Standing face-to-face on the infield last Thursday in the twilight before an exhibition game against the Angels, the 23-year-old first baseman from Texas and the 24-year-old shortstop from Taiwan choreographed the celebratory handshake they plan to employ for the next seven months, an elaborate blur of fist bumps, chest thumps and hand slaps that would make even Jose Reyes and David Wright take notice. When Loney and Hu were satisfied with their timing, the season could begin.

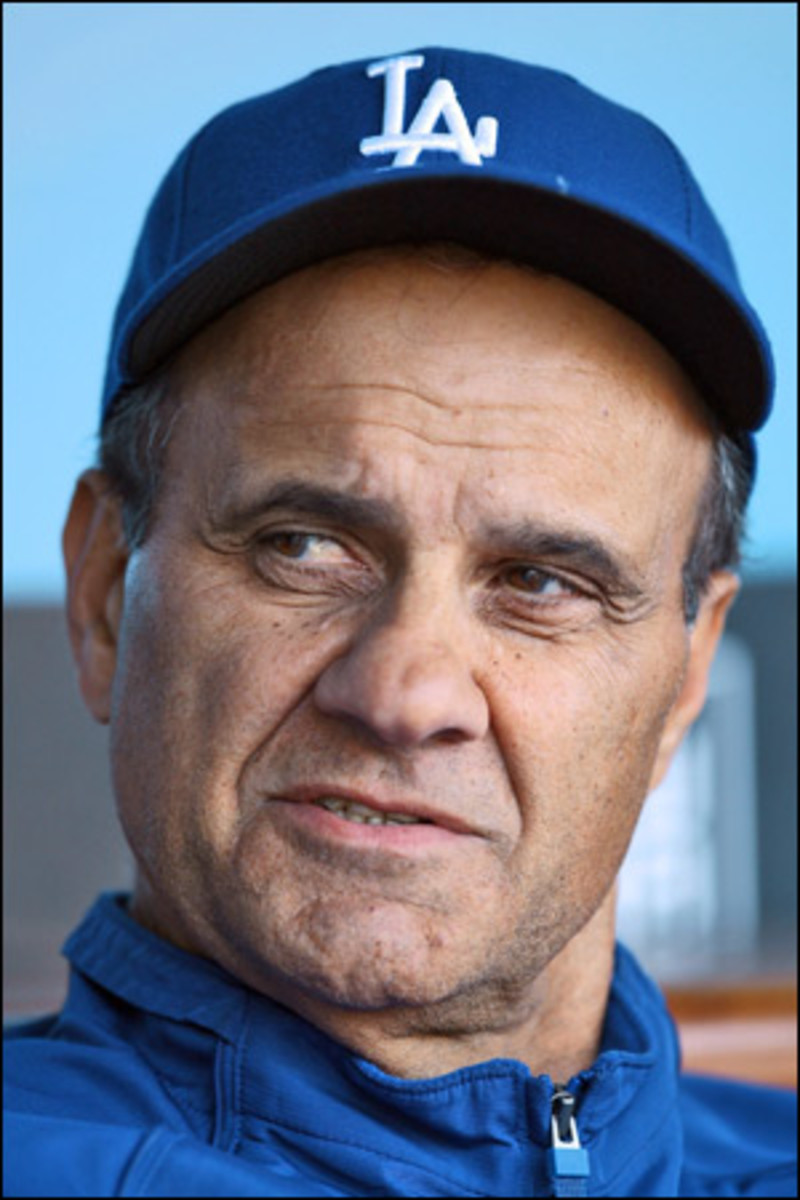

Theories abound as to why Joe Torre is managing this season, and more specifically why he is managing the Dodgers. The truth may lie somewhere in that secret handshake. Last summer, when Torre was still in the Yankees' dugout, he and his coaches would eye the out-of-town scoreboard between innings. Larry Bowa, the third base coach, would often pipe up, "That Dodgers team has some young guys who can really play." Torre did not think much about Bowa's remarks at the time. But he did not forget them either.

For 12 seasons in New York, Torre's job was largely one of crisis management, handling the Steinbrenners, the tabloids and the Red Sox. But there is another part of managing a baseball team, and that is the part that drew him west. "It's the fun part," Torre says. "It's watching young talent develop and grow. It's looking in the eyes of young players and sensing when they reach the point that they come to the ballpark knowing what to expect, what to do." As he spoke, the field in front of him was jammed with those very players.

Torre pointed at a few of them, shagging fly balls during batting practice. There was leftfielder Andre Ethier ("Can really hit"); rightfielder Matt Kemp ("Doesn't even know how good he is yet"); catcher Russell Martin ("A very special individual, not just his ability to play but the presence he has"). Torre stopped short of comparing Martin with Yankees captain Derek Jeter, though few others have demonstrated the same restraint.

The Yankees hired Torre in 1995, the same year that Jeter, Mariano Rivera, Andy Pettitte and Jorge Posada had made their major league debuts. Torre rode those four cornerstones, and they rode him, to four World Series titles and 12 straight playoff appearances. When asked if the Dodgers' collection of young talent is comparable to the Yankees' crop in the mid-90s, Torre said, "I don't think there's any question."

The Dodgers could practically fill a major league diamond with players drafted or signed in 2002 and '03: Loney at first, Tony Abreu at second, Hu at short, Andy LaRoche at third, Martin behind the dish, Ethier in left, Kemp in right and Chad Billingsley on the mound, with Jonathan Broxton in the bullpen. Four of those players -- Martin, Loney, Kemp and Ethier -- were in Torre's Opening Day lineup at home on Monday, when Los Angeles beat the San Francisco Giants 5-0. Billingsley, a potential 15- to 18-game winner, was scheduled to start the third game, on Wednesday. Broxton is a top setup man with a closer's stuff. Abreu and Hu are future regulars.

Torre chose the Dodgers not because he stayed up nights studying the minor league statistics of those players, but because he grew up in Brooklyn and developed a deep appreciation for the organization's rich history. The franchise's recent history, though, less been less fruitful. Torre's ability to inspire the youngest players on this year's team -- and their ability to invigorate him -- could determine whether Los Angeles wins its first playoff series since 1988.

Torre is 67, but no one in the Dodgers' clubhouse compares him to a grandfather. Because his World Series titles all came in the past 12 years (on the biggest stage, no less) he is still very relevant to the modern ballplayer. Most of the new Dodgers spent their formative years, in junior high and high school, watching Torre's Yankees dominate. They talk wide-eyed about the 2000 Subway Series against the Mets -- "Remember when Clemens threw the bat at Piazza," Martin recalls -- as if it were a seminal scene from their childhood.

The Dodgers' youth movement began when they selected Loney with their first pick in 2002. Loney was a hard-throwing lefthanded pitcher from Elkins High in Missouri City, Texas, who had 106 strikeouts in 56 innings as a senior. But when Dodgers senior vice president Tommy Lasorda announced the pick on a conference call, he referred to Loney as a first baseman. It was no accident. "I think that was the first sign we were going to do things differently," says Dan Evans, L.A.'s general manager from October 2001 until February '04.

In the second round the Dodgers picked Broxton, a starting pitcher they turned into a reliever. In the 17th round they tabbed Martin, a third baseman they saw as a catcher. The following year they spent a sixth-round pick on Kemp, who had been offered basketball scholarships by Oral Roberts and Wichita State. Then they took a 39th-round flier on LaRoche, the little brother of Adam LaRoche, now the Pittsburgh Pirates' first baseman.

Evans sent this glut of talent to the place where 60 years' worth of new Dodgers have gone to grow and bond: Vero Beach, Fla. During spring training, minor leaguers lived in the Dodgertown dormitories, three or four to a room. To teach the next generation about the team's history, Evans and two of his front-office henchmen, Bill Bavasi and Terry Collins, instituted mandatory hourlong classes, twice a week, often in the Sandy Koufax and Walter Alston rooms. Guest lecturers included Maury Wills and Don Newcombe. Pop quizzes included questions such as, "Who was number 4?" If a player correctly answered Duke Snider, he won a gift certificate to Applebee's or Chili's.

"If you were ever late," Martin says, "they would make you do a whole presentation about Gil Hodges or Jackie Robinson."

During spring training, minor league games are usually held on a back field at 1 p.m., the same time as the major league games. Evans, though, frequently moved the minor league start times up by an hour, so the big league coaches could watch the first few innings. While the Dodgers had been pioneers in player development, their farm system the envy of baseball, they had become too reliant on pricey veterans who often let them down. Evans wanted the organization to get comfortable again with the kids.

Late in the 2002 season Evans flew to Vero Beach to watch a few of the prospects play a game in the Class A Gulf Coast League. He remembers seeing three or four perfectly executed bunts, two or three precise relays. Afterward he told the coaches, "I can't thank you enough for teaching these young guys to play the right way."

Scouting director Logan White wanted the youngsters promoted in bunches, to foster chemistry for the day they would arrive at Dodger Stadium, presumably together. Many of them spent 2005 at Double A Jacksonville, winning the Southern League title, and from then on they were all known as the Jacksonville Five. The nickname was misleading, because there were many more than five. The group picked up an extra member in December '05 when Ethier was acquired from Oakland in a trade. The Dodgers had noticed him a few months earlier when he'd played alongside Kemp, Loney, LaRoche and Abreu for the Phoenix Desert Dogs in the Arizona Fall League.

In 2002 the Dodgers were ranked 28th in organizational talent by Baseball America. By '06 they were first. By mid-June of that season, Ethier, Martin, Kemp, Loney, Broxton and Billingsley, none of them older than 24, had all made their major league debuts. By the end of '07, LaRoche, Abreu and Hu had joined them. After the Dodgers left Vero Beach for the last time this spring, hitting instructor Mike Easler pondered Vero's baseball legacy. "It's these young guys. They are the last products of Dodgertown."

When the Dodgers are in the field, Torre and Bowa sit next to each other on the bench. If a player makes a mistake, Torre asks Bowa, "You want to talk to him, or should I?" Bowa usually responds, "I got it." While Torre is preternaturally calm, Bowa is his fiery alter ego, the enforcer of his boss's beliefs. Bowa is impressed by the team's young players but not yet sold on them. This spring they put him through a series of ulcer-inducing moments -- Kemp sliding headfirst into third base when Loney was already standing there; Hu swinging at a 2-and-0 pitch when Los Angeles was down by four runs in the eighth inning. On at least one occasion Bowa was heard shouting in the coaches' room at Vero Beach, "These young guys have got to learn!"

That was the basic sentiment voiced last September, when the Dodgers lost 10 of their final 13 games, and second baseman Jeff Kent said of his younger teammates, "I don't know why they don't get it." Asked exactly what they did not get, Kent said, "Professionalism. How to manufacture a run. How to keep your emotions in it."

When Loney was asked the next day if it bothered him to be called out by a team leader, he told the Los Angeles Times, "Who said he was a leader?" Kemp then added the most relevant point of all: "If you take the younger guys away, do you have a team?"

Loney and Kemp had been taught, since their first days at Dodgertown, to stick together. The young players ate as a group, watched movies as a group and advanced as a group. But when they all convened at Dodger Stadium last summer, en masse, they looked to older players like a threatening mob. Kemp batted .342, Loney .331, Martin .293 and Ethier .284, keeping the team in contention while taking at bats away from veterans like Luis Gonzalez and Nomar Garciaparra.

Only a few managers could bridge the generational divide in such a clubhouse, and Grady Little was apparently not one of them. When Torre declined a one-year extension with the Yankees in October, the Dodgers pounced. Little resigned. "Joe has seen almost everything and handled almost everything," says L.A. general manager Ned Colletti. "That's what makes him so special -- he has succeeded with veteran players, and a lot of people forget, he has also succeeded with young players."

In 1996 Torre managed, among others, Wade Boggs, Dwight Gooden, Darryl Strawberry, Tim Raines and Cecil Fielder, all veterans on the downside of their careers. He persuaded them to accept limited roles and defer to new stars. Now, Colletti has left Torre with Garciaparra and Juan Pierre. Torre will have to figure out how to use those spare parts, and if he cannot use them, how to keep them from disturbing the peace.

If history is any indication, he will apply the famous Torre touch, blending young with old. During a meeting in spring training, he told the players, "You don't have to be best friends. You don't have to go to dinner together. You don't even have to like each other. But when you're on the field, you have to unite." It was a variation of a speech he would give to any team, before any season. With the Dodgers, though, it took on greater significance. "He does well with young players because he makes them accountable," Kent says. "If you challenge young players, if you set expectations for them, they will respond. If you just allow them to move along, you will get no response."

Two days before the opener, the Dodgers played an exhibition game against the Red Sox at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum before an announced crowd of 115,300, the largest ever to see a baseball game. Wherever Torre goes, the Big Top follows, and, it appears, the Red Sox too. The leftfield fence at the Coliseum was only 201 feet from home plate -- 24 feet shorter than the fence at Lamade Stadium, home of the Little League World Series. Ethier was the Dodgers' starting leftfielder, but he lined up in center, and Andruw Jones was the centerfielder, but he lined up behind second base.

The Dodgers had last played at the Coliseum in 1961, and in September of that year, Torre came through town as a rookie catcher with the Milwaukee Braves. In the series finale Don Drysdale started for the Dodgers. Koufax closed. In the 11th inning Torre hit a go-ahead single off Koufax to score Eddie Mathews. But in the bottom of the 11th, Snider came back with a bases-loaded, two-run single to win the game. "I got a hit off Sandy Koufax," Torre says. "That's what I remember about the Coliseum."

Being with these Dodgers can bring out the chest-thumping rookie in anyone.