R.A. Dickey writes of confronting darker sides of human nature

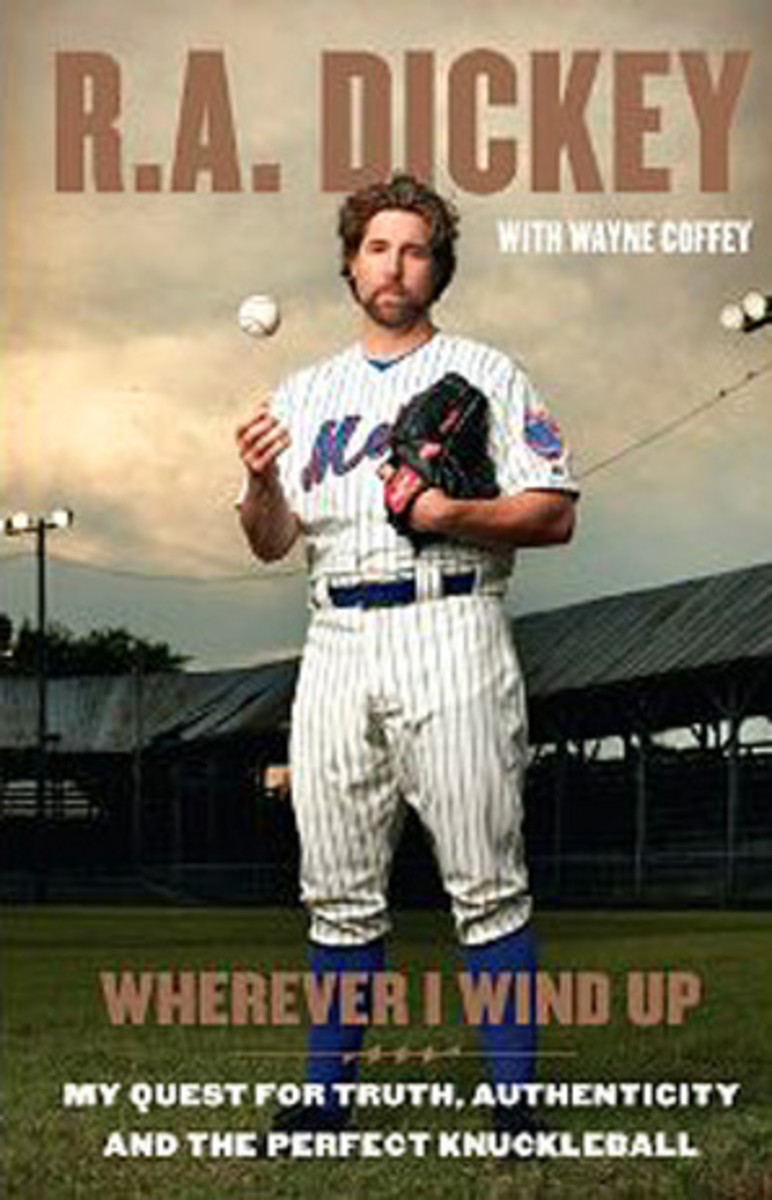

From WHEREVER I WIND UP: My Quest for Truth, Authenticity and the Perfect Knuckleball, by R.A. Dickey with Wayne Coffey, published by arrangement with Blue Rider Press, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc. Copyright © 2012 by R.A. Dickey.

It's 2001, and I'm getting my first taste of the majors, at age 26, with the Rangers. I'm throwing the ball pretty well, starting to believe that I can get big league hitters out, slowly settling into the daily rhythms of life in the big leagues.

In the bathroom one day before a game, I turn to get a towel after washing my hands and notice something underneath one of the stall partitions. I take a step closer.

It is a syringe.

The sight of it makes me cringe, the shiny thin needle lying randomly on the tile floor. My mind races with thoughts about how and why it got there. I know as much about needles as I do about jewelry, but I'm pretty sure this isn't a sewing needle. I don't know if this syringe injected a Ranger with insulin or cortisone or B12 or anabolic steroids, though you can hazard a guess when you run through the roster of my muscle-laden teammates. I'd never seen a syringe in a baseball clubhouse before. I've not seen one since. It may have been used for the most benign of purposes, but the mere sight of it makes me feel as though I am looking straight at Evil -- like seeing a weapon somebody left behind at a crime scene.

I walk out of the bathroom and never tell anybody what I saw. I try hard to think the best, but whatever chemical residue is in that particular syringe, there's no denying the scope of the wreckage caused by needles around baseball, and by all the artificially fueled feats that came with them. I know two things about performance-enhancing drugs: they are pervasive, and I hate them, because they have hurt the game, and hurt me too. How many long balls hit by juicers would've died on the track and gotten me out of an inning if not for the extra muscle? How many balls muscled over the infield would've wound up in guys' gloves? I will never know. Nobody will. I don't stay up nights thinking about it. I don't forget the sight of the syringe on the bathroom floor, either.

*****

A hot night in the middle of a hot Nashville summer, and the air is as sticky as cotton candy. I am heading into fourth grade. I've spent the whole summer doing summer things: going swimming, staying up past my bedtime, playing baseball.

One Saturday my mother tells me she is going out that night and is leaving my sister and me with a babysitter. It's somebody new, my mother says. She's supposed to be very nice.

We drive over to a condominium and my mother introduces me to the new sitter. She is 13, a tall girl with an athletic physique and fair skin and long brown hair. She does seem nice. My mother goes over the basics -- bath, bedtime routine -- and lets her know what time she'll be back.

The babysitter and I are alone in the foyer. How old are you now? she asks.

Eight, I reply.

The condo has a den with a television and stereo equipment. She puts on some country music, and I find a big, bulbous set of headphones and bop around the room to Elvira by the Oak Ridge Boys.

Why don't we go upstairs, the girl tells me. I like it in the den, but O.K., she's the babysitter. She takes me into a bedroom with a four-poster bed and a bunch of pillows and stuffed animals scattered around on top of it. The bedroom is pink and frilly.

What are we doing here? Did she bring me up to play hide and seek or something? I think.

Downstairs in the living room, the babysitter's mother and my mom and a group of friends are having drinks and talking before they go out.

The babysitter chucks the pillows and stuffed animals out of the way. She looks at me and says, Get in the bed.

I am confused and afraid. I am trembling.

The babysitter has her way with me four or five more times that summer, and into the fall, and each time feels more wicked than the time before. Every time that I know I'm going back over there, the sweat starts to come back. I sit in the front seat of the car, next to my mother, anxiety surging. I never tell her why I am so afraid. I never tell anyone until I am 31 years old.

I just keep my terrible secret, keep it all inside, the details of what went on, and the hurt of a little boy who is scared and ashamed and believes he has done something terribly wrong, but doesn't know what that is.

*****

I am in a small space, surrounded by concerned faces. The topic of the day is my lifelong run as a conventional pitcher. It is being decided on a sofa in Buck Showalter's office. The sofa is comfortable, but I am not.

Across from me are Buck, pitching coach Orel Hershiser and bullpen coach Mark (Goose) Connor. It is mid-April 2005, nine years after the Rangers drafted me. I've been a member of Buck's staff for the last two seasons, my first extended time in the big leagues. I am not even as good as marginal. My ERA was 5.09 in 2003 and 5.61 in 2004, and I give up a bunch more hits than innings pitched. I have enough promising moments to convince the front office to keep me around, but as hard as I compete I can't seem to sustain any success.

Two days earlier, against the Angels, I'd thrown a sinker and felt as if I'd been stabbed in the right shoulder. The pain landed me on the disabled list and now on my manager's couch. My senses are on high alert, noticing everything from the tight weave of the carpet to the reddish, round contour of Buck's face.

After you finish rehabbing your shoulder, what would you think about going back to the minors to become a knuckleball pitcher? Orel asks. We think it's your best chance for success. You have a good knuckleball already. You have the perfect makeup to make it work, because you know how to compete.

I squirm on the sofa. Orel and I have had some general conversations about this but nothing concrete. I've done bullpen sessions for him in which I've thrown nothing but the knuckleball. He's always been positive and supportive. Positive is exactly what I need right now, because I'm full of doubts and short on hope, a 30-year-old journeyman whose career is hanging by a glove string.

O.K., so not many people have confused me with Nolan Ryan. But still, I've always been able to throw 92 or 93 miles per hour. I became an All-American at Tennessee and an Olympian and a first-round draft choice because I had a big league fastball and a big league changeup. Now I am supposed to say goodbye to all that and join the lineage of Hoyt Wilhelm and the Niekro brothers and Charlie Hough?

It is what I have to do, because radar guns don't lie, and this whole spring, my fastball has been topping out at 85 or 86. My arm feels fine and I cut the ball loose, and what? Nothing.

In my heart I know what is going on. I know my arm is spent. I have no backup plan if the Rangers let me go. Worse still, I have lost all belief in my ability. I feel overmatched. I imagine a future making widgets on an assembly line.

So I look at Buck and Orel and Goose, and I tell them:

I'll do it. I'll go to the minors. I'll become a full-time knuckleball pitcher.

I stand up and shake hands with all three of them, a life-changing, seven-minute meeting complete. I feel as if a weight has been lifted, as if they're throwing a lifeline to me. Who cares about throwing 90? I'm tired of being average, or worse. Tired of being lost, hiding on the margins of life and the Rangers' roster. Tired of pretending I am something I am not. I have no idea how this experiment is going to go, but I can't wait to find out.