SI Vault: The Streak: A native son's thoughts on Baltimore and Cal Ripken

This story first appeared in the Sept. 11, 1995 issue of SPORTS ILLUSTRATED.

It's a stinkin'-hot night at the ballpark-near 100 degrees, the air is code red—and the Orioles are playing the cellar-dwelling Blue Jays. Still, it's got to be a big night: It's Coca-Cola/Burger King Cal Ripken Fotoball Night. That is, it's the sort of ersatz event that is a staple of baseball now that payrolls are fat, attendance is slim, and the game—well, no one trusts the game to be enough. These new Orioles yield to no club in the promotional pennant race. There's Floppy Hat Night, Squeeze Bottle Night, Cooler Bag Night. There's an item called the NationsBank Orioles Batting Helmet Bank, and there's the highly prized Mid-Atlantic Milk Marketing Cal Ripken Growth Poster. They are all a stylistic match for the graphics on the scoreboard that tell you when to clap or the shlub whose bodily fluids are draining into his fake-fur Bird Suit while he dances on the dugouts for reasons known only to him.

Still, as a celebration of the Hardest-Workin' Man in Baseball, the hero of this Old-Fashioned Hardworkin' Town, the Cal Ripken Fotoball is my personal favorite, perfect in every detail. There is the F in the name—gives it klass, and it's korrect, because there's no photo on the ball. There's a line drawing of Cal's face, with a signature across the neck. The signature is of the artist who made this genuine-original line drawing from a genuine-official photo of Cal. And then there's the plastic wrapper—says it's all Made in China. I like that in a baseball. And one key word: NONPLAYABLE. In other words, don't throw or hit it, or this fotobooger will come apart.

Hours before game time, I wanted to ask Cal about his Fotoball. I wanted to ask how it feels to be the icon for baseball and Baltimore. But he's hard to catch in the locker room. He has his locker way off in the corner, where his dad used to dress as a coach. The official-and-genuine Oriole explanation is that the corner affords him room for two lockers—one extra to pile up all the stuff fans send him. But it's also unofficially helpful that there's an exit door in that corner, and anyway it makes Cal plain hard to get to. (One day early in the season I was blocked entirely by the richly misshapen and tattooed flesh of Sid Fernandez.) And if you're lucky enough to catch Cal, you're still not home free: Even local writers--guy Cal knows--find that out. "Angle your story," he might say, without looking at the writer, his eyes still on the socks in his hand. "Yeah ... but what's the angle?"

So the writer must explain what he means to write. "Cal, it's just about all the second basemen you've had to play with--you know, 30 different guys to get used to."

"No," Cal says to his socks. "Doesn't do me any good to answer that."

See, these days, just a handful of games from Lou Gehrig's record of 2,130 consecutive starts, he's playing writers like he always plays defense, on the balls of his feet, cutting down the angles: How is this gonna come at me? Where should I play it? Positioning (forethought, control) has always been his game. And streak or no streak, Cal still has to play the game his way—that is, correctly: He's got to click with his second baseman.

This new locker room defense is the only effect Cal permits himself to show as he surfs the hype wave into the record books. That and maybe some testiness toward umpires. Just a couple of nights before Fotoball, the second base ump missed Cal's tag on a runner, and for the next 10 minutes obscenities and spittle flew out of Ripken's mouth. (Of course, Cal did it the right way, facing home plate while he manned his position, never turning his head, so the ump wouldn't be shown up and have to toss Cal out. Ripken, being Ripken, has to throw even imprecations correctly.)

The point is, the umps, the writers, even the Streak itself, they all get in the way of the goal—always the same goal—which is to play the game just right. The umps make mistakes. The writers don't care, they want controversy. Cal doesn't like controversy. And the writers take time. Caldoesn't have time, not now. He's got his wife and kids in the big country house; he doesn't get enough time with them already. He's got fans, he gives autographs—thousands of signatures. He's got press conferences at ballparks across the country and big, scheduled media hits—The New York Times, Prime Time Live, TV Guide, the cover of SI. He's got endorsement deals, his old ones (local hot dogs and milk) and new ones: Chevy Trucks, Coca-Cola, Nike, Franklin Glove, the Adventureland theme park, and assorted memorabilia, including a bobble-head doll. (You can't establish a deathless baseball record without a bobble-head doll.) It's not easy being an icon--when it has to be done just right.

And time before a game...well, forget it. That's sacred. That's Cal's time to prepare. He's in his routine—the silence, the planning, the discussion. And he wants to hit, take batting practice, correctly: first a bunt, then a ground ball to the right side (move that runner to third), then a fly to the outfield (bring that runner home) and then swing away, swing away, swing away. He wants to take grounders—has to take grounders—but correctly: You don't grab the ball any which way and close your mitt around it; you catch the grounder with an open glove, to get your throwing hand in. You catch it in position to throw. That's all part of catching the grounder correctly. See, Cal's dad, who taught him, has these sayings—said them all a million times—like: If you want to play the game properly, you have to get ready to play.

Or there's this one:

You have to know what you want to do before you can do it.

And even more often, there's this one:

Practice doesn't make perfect. PERFECT practice makes perfect.

So there's Cal on the Camden Yards ball field, trying to practice perfectly to get ready to be perfect, and I'm lurking in the dugout—I wanna ask about the Fotoball. That's the funny thing that happened to Cal: He landed in all this hype and distraction, the reporters and the shoe deals and about a thousand plaintive kids screaming, "Cal!" "Cal, pleeeze!" "Mr. Ripken!" "Caaal!" He's got hungry little Baltimore to feed with esteem. He's got Powerade and Fotoball. He's got me to deal with, and every other sideshow in the whole Hoopla Nation ... because he was raised to pay attention to the game.

Here's the funniest thing that happened to Ripken: Now that the calendar, luck and stubbornness have made him Baltimore's hero, the team, the media and the city's nabobs have decided he's got to be a blue-collar hero.

Oh, young Cal...he was raised a Baltimore, you know....

That's how the local song begins.

...So he grabbed his lunchbucket and went to work every day—the way guys do in this hardworkin' town. He did his job 13 years straight—like the fellas on the swing shift at Crown Cork 'n' Seal....

Well, a workin'-class hero is something to be. But it just doesn't happen to be...him.

At $6 million a year, Cal Ripken Jr. lives in a house the size of a Wal-Mart, near the ninth jump of the Maryland Hunt Cup, in steeplechase country, the Greenspring Valley, along with the other rulers of Baltimore. Ripken goes to work in a chartered plane or in the Orioles' fashionably retro theme park.

And the town? Well, that's a complicated story—one that goes well beyond the Camden Yards theme park and the surrounding Inner Harbor theme park, with its rows of shoppees selling $20 T-shirts or crabs at $35 a dozen. None of that is meant for the man on the swing shift. In fact, there is no more swing shift. Crown Cork and Seal closed up its plants, like all the other big manufacturers.

The ball yard, Harborplace, the gleaming insurance and banking towers looming over the gleaming water-—they were all designed (with forethought, control) to replace the blue-collar Baltimore that was crumbling like an empty row house. Or at least to distract attention: Here the rulers of the town would build the Baltimore you're supposed to see; they would stock it with family attractions—the shoppees, tall ships, an aquarium (Hey! How 'bout baseball?)...and plenty of parking, so the white people could jump into their cars and go back to the suburbs to sleep. They wanted the kind of place that Good Morning America would visit. If you build it, Joan and Charlie will come! And so they did! That worked like a charm. In fact, that's what they called Baltimore: Charm City.

But somehow that name never really stuck. See, the schools still didn't work, crime's a problem, taxes are murder. And even those new towers shining out there, beyond the centerfield fence, they're going empty. This town is literally shrinking up. Somehow, all the Disneyfication of the downtown didn't win for Baltimore the label that the rulers really wanted: big league. Now they've given up on the catchy nicknames. They've just mount ed Cal up front, like a hood ornament, to symbolize what Baltimore's all about.

The truth is, Cal wasn't raised a Baltimore—nor even a true son of Aberdeen, Md., the town 33 miles up the highway where his parents still keep their house. When Cal was growing up, the Ripkens' home was baseball. Young Cal was raised an Oriole.

You have to understand what it meant. When Cal was growing up, the Orioles were the best club in the game. There were pennants: '66 (world champs) and '69, then '70 (world champs again) and '71. There were playoff teams in '73 and '74 and a pennant again in '79. These Orioles were stars on the mound: Jim Palmer, Dave McNally, Mike Cuellar. They were sluggers at the plate: Frank Robinson, Boog Powell. They were stars with the glove: Mark Belanger, Paul Blair...and for 23 years at third base, Brooks Robinson.

The great thing was not what they won but how they did it. This wasn't the richest club. As a business, it wasn't even good. The Orioles had to win pennants to draw a million fans. Any evening you could leave work at 7:15 and drive like a bandit through the neighborhood in northeast Baltimore that had as its centerpiece Memorial Stadium. Everybody had his own route through those tight streets. Everybody knew a kid who parked cars in his alley or his driveway. And for five bucks at the window, you could stroll through this comfy concrete pile and settle yourself to watch the greatest righthander to hit the league in 30 years, Palmer, mow down some visiting lesser lights. By midgame, if you had the wit and nerve, you could spot an empty seat in the second or third row...you could sit, for god's sake, a foot and a half behind the bald owner, Jerry Hoffberger, hard by the third base dugout, where it looked like Brooks was gonna dive straight into your lap for that ball. "Way to dig it out, Brooksie!" some fan would yell. Brooks would look up to see if he knew him. These were ball fans. They would hoot an outfielder out of the park if he threw some rainbow over the cutoff man's head. The Orioles were all about defense. Sometimes they made brilliant plays. But they always made the routine plays right. That was the Oriole Way.

There was actually a book. It had all the plays: where the cutoff men stood, who backed up where, all the bunt plays, the pickoff plays....This was the codification of the Oriole Way. And this text was taught at every spring training and through the summer, in every ballpark throughout the organization. In Stockton, Knoxville and Elmira, they did everything the Oriole Way, down to the dress code (on the street), full uniform (on the field), batting practice (first the bunt...one to move the runner over...one to bring the runner in...then swing away, swing away, swing away). The Orioles couldn't afford to buy pennants. When they had a hole, they had to fill it from the farm. But when those kids came up, they were Orioles already. The only thing manager Earl Weaver had to tell them was the curfew. On the field, they knew how to make the plays right.

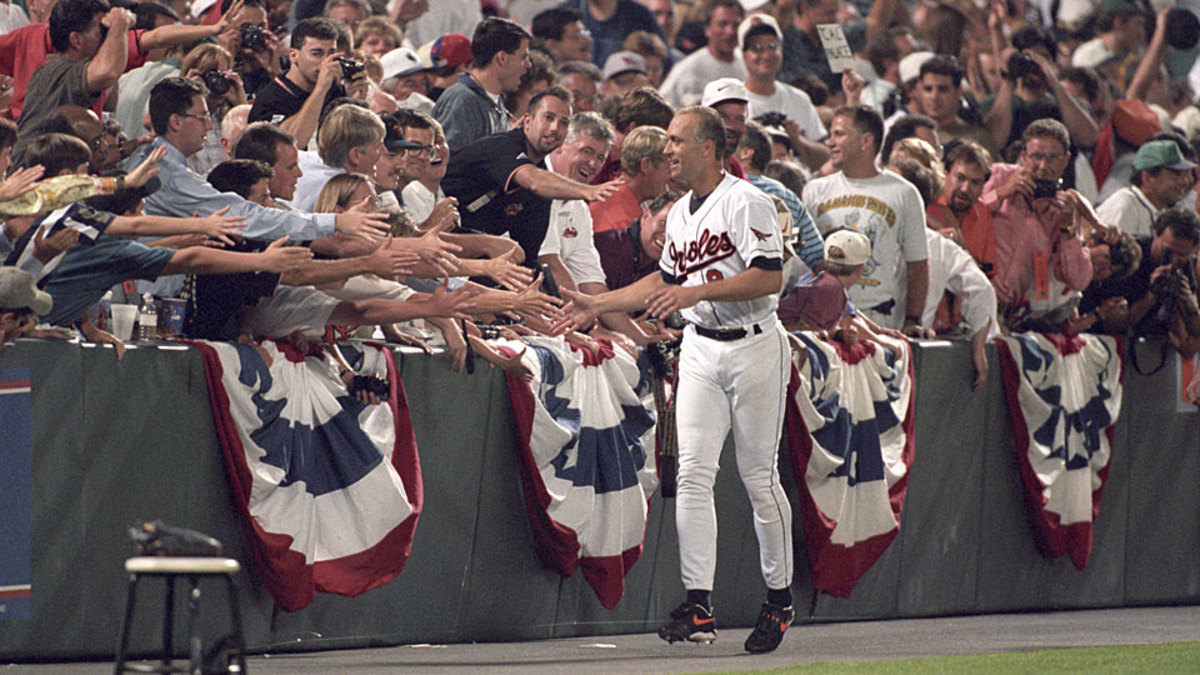

By obliging fans who yearned for his autograph, Cal Ripken helped bring baseball back from the 1994-95 player's strike.

Al Behrman/AP

And that's where the old man came in. Cal Ripken Sr. was a catcher whose playing career (1957-62) arced short of the majors. Then he was, for almost 15 years, a coach and manager in the bushes, teaching the gospel to fledgling Orioles. For all the years of his famous son's life, Senior was preaching the Oriole Way. Living it, in fact, in Asheville, Rochester or some other town where his wife, Vi, would rent a house and make a home for the four children during the summer. Wherever home was, the ball park was the Ripkens' second home. Dad would set the kids to work in the clubhouse or hit grounders to them (Dad could run a perfect infield)—100 grounders, 150, as many as they wanted—unless they started screwing around, grabbing at the ball, hotdogging throws, in which case he would pick up the ball bag and walk off. (PERFECT practice makes perfect.)

Cal Jr. didn't live in Aberdeen full-time till high school, in '75. (Senior didn't come up to the big club, as a coach, till '76.) But young Cal was already an Oriole. From the time he was able to read, the box score from Baltimore held names he knee-they'd been kids on his father's teams. (Hey! Al Bumbry went 3 for 4! Junior had shined his shoes in the Asheville clubhouse!) When Junior was drafted in '78—and made it through the system, the Oriole Way, by '81—he was just rejoining family.

And it was like family, the way the guys would go out after road games—or in Baltimore, they would babysit one another's kids, watch 'em all together in somebody's pool. Or everyone would go out to Hoffberger's house after Sunday doubleheaders: cookouts and laughter, players and ex-players, kids and wives, stadium ushers and secretaries, Weaver and the old coaches—Bamberger, Hunter, Ripken—grinning half-lit on National Bohemian beer (that was Hoffberger's brewery), saying (like they always did), "It's great to be young and an Oriole!" And it would go from just after the game to ... well, when the last guest left. Even on a weekday night Cal Jr. would come off the field, and there would be Dad at the table in the locker room, holding court--Senior never liked to leave too quickly after a game. And he would take apart that game, too, for a couple of hours sometimes, and you could learn some baseball. Cal Jr. liked to hang around like Dad. And even if he stayed for two hours, he'd still see guys—Palmer, Elrod Hendricks—in the parking lot, fans around their cars. Autographs were mostly for kids. When that was over, they could talk baseball.

And the baseball was splendid. In '82, Cal Jr.'s first full year, the Orioles took the pennant race to the final weekend against Milwaukee. That was the most exciting thing Junior had ever felt in his life. The next year they took it up a notch and won the pennant in the playoffs in Chicago. Attendance was sky-high. All of Baltimore was on a roll. There was a working mayor in those days—guy named Schaefer, he was kind of the Oriole Way of mayors—and he'd walk into some business in town and tell 'em, flat out, they had to buy season tickets. That's when he wasn't busy building somewhere. (Hell, he was rebuilding the whole Inner Harbor, said it was going to save the city!) It was exciting just to be there. And when the O's beat the Phillies in five games in October, and Schaefer had a parade through the streets, and the fans came out by the tens of thousands, yelling, "Cal M-V-P, Cal M-V-P!" ... then everything seemed perfect. Nobody knew it was over.

No one had marked as a disaster the moment three years earlier that Hoffberger sold the team. (The new owner, attorney Edward Bennett Williams, was already whining about the tight streets around the ballpark. Fer crissakes, it took him an hour to get home to Washington.) No one knew the mayor was running for his last reelection; he was building his last towers, selling his last tickets. No one—certainly not Cal Jr.—knew that would be his last pennant, last Series, last parade. No one saw it was the end of the Oriole Way—not even Senior, keeper of the code—until four years later, when Williams gave him a thoroughly diminished team to manage and then fired him because he didn't win.

Sure enough, it's a big crowd for Fotoball. No surprise: Camden Yards is always near-sold-out. The field level is almost all season tickets. The club level, above that, is all bought up by businessmen who send young waitresses to fetch their crab cakes and designer beer. And it's big business in the skyboxes, where buffets and TVs are arrayed in cool darkness, behind plate glass. The rulers of Baltimore built this pleasure playground for themselves.

Though he had just 17 home runs all year, Ripken went deep in games 2,129, 2,130 and 2,131.

Porter Binks/AP

In the rest of the yard it's family entertainment--parents cajoling little Kim, Lee and Ashley to keep their Fotoballs in the Oriole (promo) sports bag so they won't get cotton candy or frozen yogurt on them. It's a prosperous crowd, overwhelmingly white. The P.A. man, Rex Barney, yells his single, aged joke—"Give that fan a contract!"—whenever a customer catches a foul ball. There's the Bird dweeb, dancing with the ball girl down the leftfield line. There's the Jumbotron in centerfield, flashing trivia quizzes (JeopBirdie) or guess-the-attendance or a picture of the player at bat, along with some cheery bio factoid: Chris had 3 HR in one game with Columbus. (Big deal.) The whole show is paced like a Saturday-morning cartoon: Something has to happen every 30 seconds, or else.

Oh, there is a game, too.

It isn't a very good game—though Cal puts the O's on the board with a home run in the second inning. That revs the crowd for a while. They're up in their seats, rooting ... till the third out, and then the P.A. speakers whine to life with a female voice like treacle: Noo-body does it better.... It's the theme song for the Jumbotron video on Cal: Cal hitting, Cal sliding, Cal high-fiving, Cal in the pivot, Cal as a kid, Cal with his kids, Calgetting a plaque, Cal in gauzy sunshine waving his cap. Noo-body doezzz it bettttter. Bayyyy-bee yerrrrr the besssst! The boys in marketing must have put that splendid tribute together. No one is rooting at all—they're just watching TV. Cal is already the favorite with all the suburban children. They wear jerseys with the big number 8 on the back and ORIOLES across the chest. (No official-and-genuine Oriole jersey, not even the road uniform, says BALTIMORE anymore. Regionalism is a Key Marketing Concept.)

Meanwhile, the O's are giving the game away--handing it over to a last-place club. On the mound Jamie Moyer has already walked in two Toronto runs. Now, two ground balls that the second baseman can't play and an error in leftfield turn into three more runs. The nearly 42,000 in attendance watch in murmurous passivity. They make noise when they're told to--though they did stand to cheer for Bobby Bonilla on the occasion of his first Oriole hit; he was 0-fer his first two games. Still, everyone seems sure Bonilla will put the O's over the top. Has to. He's worth millions! They're pleased with the team's owner, Peter Angelos (another lawyer). At least he's not afraid to spend! (And isn't it great? All they had to give up for Bonilla was a couple of farmhands--just two of their best outfield prospects. Minor leaguers!)

Middle innings: Toronto now has six runs. It's always disturbing to this crowd when their team of hired millionaires doesn't win. And it's always somewhat mysterious.

The front-row box next to the dugout, right on third base, is now held by Ripken's agent, Ron Shapiro. Those seats have a splendid view of Toronto runners rounding third, but Shapiro couldn't be in a better mood. He's gorgeous in his warmth—the kind of fellow who'll reach over and hold your arm with his hand while he tells you something nice about yourself. He's a lawyer by training, sports agent by trade; he's the man who set up Cal's charity foundation and created the Tufton Group, which handles demands on Cal in this year of the Streak. As Cal's father is father to Cal's game, so is Shapiro father to Cal's iconhood.

SI Vault: Legacy of Mickey Mantle, last great player on the last great team

"To me," says Shapiro, "the bonding between a player and his community is what it's all about." Ripken, he says, has made a conscious choice to stay in Baltimore for his entire career. Yes, Cal is committed to working with Baltimore. "He wants to be appreciated for his totality as a human being ... as a thoughtful, caring, committed and community human being." Shapiro is thoroughly hip to the great divide in the ballpark--the family crowd, the corporate crowd—and alive to the possibilities this presents for Cal. "Because, remember," says Shapiro, "they'll all come out for Cal. Both constituencies." He sounds like an operative sizing up a prime piece of political horseflesh. Politics is another of Shapiro's games. He is the finance chairman for the current mayor's reelection campaign. Ron Shapiro is going to remain a ruler of Baltimore.

The Blue Jays have the bases loaded (again!) when their batter, Alex Gonzalez, raps a clean hit to left ... except it never gets through. Ripkenwas moving before the bat hit the ball. He is so far in the hole, it looks as if his weight will carry him into foul ground. But he picks the ball on the bounce, backhand, with his body somehow already turning, with his right hand already sweeping up to meet his glove at his hip. He is backpedaling, almost falling toward third, when he plants his big right leg, which lifts him into the air, whence he fires the ball in a white streak to second base. And the runner is out--inning over. It is the kind of play that stays in your head as a picture. At Camden Yards, no one yells. Polite applause. The fans are waiting for the next thing to happen. "Dad.... Dad!... DAD!" This is a kid on my left. He wears a T-shirt that says CHICAGO BULLS. His father turns. "Cal's gotta hit another home run! Dad! Can we get ice cream?"

This current mayor, guy named Schmoke, made a new slogan for the city: Baltimore. The City That Reads. No one knows what that's supposed to mean. But about the same time, Cal set up his own foundation and its literacy program: Reading, Runs and Ripken. Shapiro keeps everybody on the same page of the hymnal. Cal's always been willing to sing along.

Now that Blue Collar Cal's so famous across the nation, everybody's trying to pick up the tune. Would you say there's something special about this town? Hardworkin' people? It was one of those man-on-the-street ads, supposed to thump the tub for local Channel 11. They wanted to bill themselves as the Hard-Working News Team. Of course, it seemed like a small-minded play on Cal's streak—collusive, self-satisfied and small-town. That's Baltimore too.

Though he'll never talk about it, Cal remembers clearly those times when the town chorus turned against him. There was '88, that awful year when his father was fired (the O's started 0-6 under Cal Sr., then Frank Robinson came in, and they lost 15 more in a row). And there was '92, when the team and the town gave up on his little brother, Billy (Cal's favorite second baseman, but of course he can't say that, either). In fact, every time Cal's hitting went south, those hard workin' airwaves were filled with captious comment. People said Cal ought to sit down. Take a rest. Stop acting like Superman. Stop putting his own streak ahead of the team!

It hurt him. Confused him. In '88, when Brady Anderson joined the O's, he found Cal one day leaning alone against the leftfield fence. "What's goin' on?" Brady said.

Cal just waved him away: "Not now."

Brady insisted. "No, c'mon. Tell me. What's wrong?"

Then Cal asked this near-rookie, this kid, "What does the Streak mean to you?"

What Cal couldn't figure was: How could they criticize the best thing about him? He always came to play. What was wrong with that? That's the way he was. Was there something wrong with him?

Still, he signed two contracts after that. Even in the middle of negotiations, he never made a threat to leave. That didn't have to do with Baltimore's values. It had to do with his values. He thought if you say you're willing to leave—if you declare for free agency—then you have to be willing to go. He wasn't.

And that's his real link with this town, with the people in the row houses. City councilman Martin O'Malley (who is to local politics what Cal was to baseball as Rookie of the Year) represents those old, tight streets around the silent Memorial Stadium. "People here don't care where he lives," O'Malley says. "Or how. They don't want him to be blue collar. And they're not waiting with bated breath for him to pass Lou Gehrig. You know, the city can ebb and flow. We've got racial divisions. We're best known for Homicide on TV. The population's at its lowest point since World War I. But number 8's still trottin' out to shortstop. People see that. He never gave up on them."

Cal does hit another home run. Two dingers on Fotoball Night—how 'bout that? But it isn't enough, not when the rest of the lineup hits nothin', and the O's give away three or four runs. Toronto six, O's three—final. The Orioles have departed second place, heading south.

It promises to be a somber clubhouse scene when the writers are admitted 10 minutes after the O's last strikeout. The pack makes for the manager's interview room. I am hunting Cal, still with my Fotoball, still without avail. Often after games he'll sit for a while in the lounge-players only-to talk about the game. But tonight it looks like the rest of the guys are getting dressed, heading out. Coaches, too. It is almost 11 o'clock. I watch Cal's corner. A camera crew, for mysterious reasons, is filming his locker, shining a minicam spotlight onto his shoes, his chair, his uniform shirts. (Maybe it's another Jumbotron tribute. Maybe they'll make this one scratch-'n'-sniff.)

"Check the field." This is whispered in my ear in the locker room. "He's out there. You better check it out."

I go out through the tunnel, under the empty stands. Except they aren't empty. There are thousands of people, all standing, looking down at the rail where Cal Ripken is signing Fotoballs.

Cal has one foot on the rubberized warning track, one foot on the padding of the rail. He has his own felt-tip. And he is signing-correctly, of course, down to the Jr and the period after his name. (Then he blows on his signature to make sure it won't smudge.) There are city cops around him and two dozen ushers to keep the crowd in line. But mostly they just stand there grinning. This is just Cal and the fans.

"Cal, would you put 'From B.J. to Kristin'?" "Kristin with a K?" "K-R-I-S-T-I-N.... Thanks, Cal." "You're welcome," Cal says.

He signs their Fotoballs and then their programs—or their shirts, ticket stubs, popcorn boxes, whatever they want, as many as they want. If they want him to use their pens, he caps his and signs with theirs. (One guy's pen doesn't work, so Cal rubs the point on his own palm till it satisfactorily marks up his hand.) If they don't ask him something, Cal asks them. "Favorite hat?" Cal says as he bends to sign one kid's sweaty headgear.

"It is now," says one of the cops.

Cal never lets a kid leave without a word from him. "You ready for bed?" Cal says to a yawning little girl. "I feel that way, too."

But he doesn't look ready for bed at all-stoked up is more like it, in high enjoyment. He doesn't just hold out his hand for the next ball and the next ball ... he looks up and fixes each fan with the shock of his light-blue eyes and a greeting. The cops warn him a couple of times that fans are still piling into line in the concourse-the line stretches now from the right side of home plate halfway to the leftfield corner. "That's O.K.,"Cal says. He keeps signing and talking.

"How'd you break your arm?" he says to a boy as he signs his cast, then his Fotoball, then his hat. "Your bike? Jumpin' a couple of cars? Or you just fell off.... How long you got to have it on?... Well, that's O.K. You can still play other games, can't you?" (The kid just shakes his head, mute with awe.)

The grown-ups, who didn't get Fotoballs, bring Ripken whatever they have. One woman hands over her shoe. "I'd like to sign it inconspicuously," says Cal, turning it over, "so you can still wear it." Says the woman: "I'll wear it." Maybe a hundred parents push kids forward and then back away, making motions of entreaty with their cameras. Each time, Cal leans in next to the kid-"Cheese," he says. ("Oh, didn't wind? Try again. Cheese and crackers.") Teenage girls are in that breathless, open-mouthed, near-tears state known to doctors as Deep Elvis. They want to kiss him. Cal demurs. They want to hug him. Cal leans in. "Not too close," he'll say. "I'm all sweaty." (They don't mind.)

At midnight it is still near 90 degrees on the field. The rest of the vast yard is silent and empty, in a strange surfeit of light. The grounds crew has finished with the mound, home plate and infield. The rest of the stands are clean and bare. Supper has long since been cleared in the clubhouse. The locker room is also empty save for a couple of attendants cleaning, putting laundry away. Still there are fans, stretched in a line down the concourse. And Cal keeps signing: "Is that Katie with an i-e?"

The police lieutenant, Russell Shea, leans in behind Cal. "I'll be the bad guy, O.K.?" he says. Cal nods but keeps signing and talking. Shea calls Cal "the finest gentleman I've met, bar none—and I've been stadium commander for two years." So he lets Cal make the schedule. He leans in again: "You want anything? Cold drink?" Cal shakes his head. He is still in full uniform, his forearms shining with sweat, his ankles still taped. For most of the last hour and a half, he has stood on one leg while he propped each ball, photograph or program on his left knee-so he could sign just right. Shea, unbidden, brings a bottle of Powerade. Cal keeps signing.

"Let me stretch out your shirt, so I can sign it right." "Yeah, this picture's rookie year. You want me to sign on this leg?"

The way Cal describes it, he's too pumped up after a game to leave. His family's asleep ... and the fans want so little—a picture, a handshake, a signature to remember the night. He likes it when they ask him to write their names too-or when they bring pure trash for him to sign (some lemon-ice wrapper that has been on the floor). That way, he knows: They never mean to sell it. (The one piece he won't sign is a pair of uniform pants brought down by a collector. The guy would have sold the pants for a fortune.) He likes it when fans ask if he remembers them or they bring up some name he's supposed to know. ("Do you know Pat Francis?" asks a big-haired blonde. "She useta babysitcha." Cal fixes the woman with an elfin smile. "We used to tie up our babysitters sometimes. We outnumbered 'em." And the woman is giggling.) The way Caldescribes it, if he can talk with a thousand Baltimore fans, he'll find out he knows most of them. That isn't true. But it pleases him to think it's true.

It pleases him to see the excitement on their faces—and their shock. (He talked to us! He was so nice!) It pleases him to do this correctly. It pleases him, this power to give some bit of himself (as the kids yell to one another, as they run with their autographs: We got Cal! We GOTCAL!). This is a heady power: On this night or any night, at any hour, midnight or after ... by his act alone, by his attention for one minute, by a stroke of his pen, he can give value to trash. He can make a night, or a town, feel big league. He can make even Fotoball something real.

Quarter after 12. What he can't do is stop. Not easily. Not tonight. There are hundreds left in the concourse when Cal murmurs, "Pen's going." That means he is going—soon. But he signs a few more, till the collector with the pants shows up again. ("I didn't come to argue. Cal! Just these pictures!")

"I'm done," Cal says. He caps his pen.

"CAL! Ooooowww!" It is a moan of near-physical pain from a mother-with-son behind the collector--a kinda-cute mom, with curly brown hair. "Pleeeese, oh, god!" She's been waiting with her hyperweary kid for hours.

"I'm done," Cal says. "Sorry. I can't do any more." He is heading down the dugout steps. She is going to cry—you can see it. "But how 'bout if I give you my cap? Is that all right?"

The mother doesn't get it. She looks at her stunned son to see if that is all right. Cal ducks in the dugout and surreptitiously signs the bill. Then he pops up the steps, puts it in the kid's hands. The mother is still staring at her kid: Is it all right?

But the kid can't look up. He is staring at this ... thing. As if a meteorite had landed in his hands. Cal is already in the tunnel when the boy looks up--not at the mom but at the dark heavens--and says, "Whoa! YESSS!"