The Pocket Hall of Fame: One family's connection to baseball history

Take a long look. You may not see it again—this cracked, shoelace-bound, leather notebook inscribed with the signatures of baseball legends. Yes, that sure is Honus Wagner’s name tucked in above Red Schoendienst and Lou Brock. Flip back nine pages and you’ll see Lou Gehrig, his looping first initial seaming into a last name removed from a lineup too soon. Greg Gamble always likes a good excuse to take out the autograph book, his family’s own pocket hall of fame, which he keeps in a drawer in his Nashville home. We’ll travel back to a time when kids peered through outfield fences and radio broadcasts filled living rooms. These 60 pages are fragile after nearly 80 years. But don’t worry, the Gambles certainly don’t mind you taking a peek.

This book belonged to Greg’s father, Harry. There’s his handwritten name topping the first page. Harry’s mother, Betty, gave it to him shortly after his 1921 birth in East St. Louis, Ill. Titled Schoolday Memories, Harry tucked the 4”x8” notebook under his arm when he, his older brother Willie and several other neighborhood kids pressed their eyes against holes in the outfield fences of Sportsman’s Park to see the Cardinals play. Known in St. Louis as “The Knot Hole Gang,” these kids were unable to pay the price of admission, yet Harry willed his way to meet his heroes, where he would stretch out the book for them to sign.

Here they are now, the scribbled names of Hall of Famers filling the fading pages. The first one you can make out is that of Dizzy Dean, the St. Louis ace who helped the Cardinals to the 1934 World Series title by winning 30 games, the last National League pitcher to do so. Turn to page nine. There’s Frankie Frisch, the Cards’ three-time All-Star second baseman and the NL MVP when St. Louis won the World Series in '31. Flip to the back: There’s Lefty Grove, the opposing pitcher in that Series for the two-time defending champion Athletics, whose two complete game victories were not enough to keep the title in Philadelphia.

These are the names Harry pointed out to his three sons more than 30 years later. After serving as an Army medic in World War II, he worked as a railway clerk in St. Louis for the U.S. Postal Service, and by 1959 he was based in Sharpstown, a subdivision in Houston. That year the Houston Buffs finished their final season as the Cardinals’ AA affiliate, and radio broadcasts from St. Louis’s KMOX still reached the city.

When there was a good enough signal in their small house on Bintliff Drive, Harry would sit at the table with sons Harry Jr., Greg and Danny and fill out handmade scorecards that he had sketched with a ruler. Every now and then the father took the autograph book from the top cabinet and opened it for the huddling brothers like a fairy tale tome.

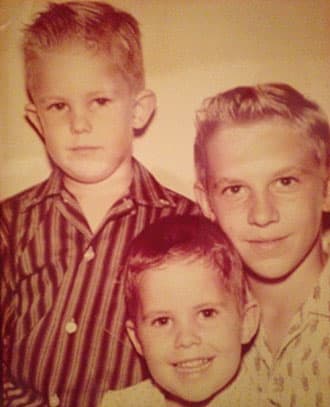

The Gamble boys—Greg (left), Harry (right) and Danny (bottom)—around the time their childhood love of baseball reached its peak.

Courtesy of the Gamble family

In 1962, the Gamble brothers got a major league team of their own, when the expansion Houston Colt .45s began play. Their mother, Betty, had given the book to 13-year-old Harry Jr. so that he could chase after his own heroes, and have them fill their names around his father’s collection.

There’s Sandy Koufax and Warren Spahn on the same page as Dizzy Dean. Harry Jr. had to walk over to the visitors’ hotel to get Koufax. Lobby workers told him that the team was on either the 15th or 16th floor. Behind the first door Harry Jr. tried he found Dodgers manager Walter Alston. Alston said he could knock on anybody’s door once or twice, and if they didn’t answer, to move along. Harry followed the sage skipper’s advice, collecting a few other autographs before he reached the room he was looking for. There were Koufax and fellow future Hall of Fame pitcher Don Drysdale standing in their underwear.

Turn the page. There’s Frank Robinson, Cincinnati’s Hall of Fame outfielder, crammed beneath the crease. Harry Jr. couldn’t catch Robinson’s attention when the Reds were idling outside Colt Stadium one day until he yelled, “Hey Robinson! Sign your name next to Lou Gehrig.”

“Where? What Lou Gehrig?” Robinson asked, and Harry pointed to the middle of the page: L. Gehrig. Robinson signed—and then called over Vada Pinson, the Reds’ All-Star centerfielder, who said “I’ll be damned.”

“You ain’t gonna sign there,” Harry said. “I’ll let Frank sign by Lou Gehrig but you’re not gonna sign on this page.”

Vada is on page two.

Willie Mays has the eighth page all to himself. Harry Jr. can’t recall exactly how he got the Say Hey Kid, but he does remember climbing onto a pal’s shoulders and looking for players through the slats of the opposing clubhouse at Colt Stadium, where he spotted Mays taking a shower.

Hank Aaron signed next to his brother Tommie and later swatted his record-breaking 715th home run on April 8, 1974, Harry’s 25th birthday.

Projecting next five years of Hall of Fame voting: Who's in, who's out?

By then, Greg and Danny had long since inherited the book from their older brother, who gave it to them after going to college in the late ‘60s. They grabbed a few other big names—like longtime Dodgers star Maury Wills, whom they got at a Shakey’s Pizza—but the real prize of their Hancock-hunting years was Nolan Ryan. The Astros’ ace was warming up in the Houston bullpen before a start in the early ‘80s when Danny darted down and shouted for him to sign his book. Ryan glanced at the page. “Can’t do it!” he said, pumping a pitch. “I don’t sign on days I’m pitching.” Danny pleaded again. Ryan threw another pitch, “Come back tomorrow!” Danny yelled back that Ryan would be the worst player on the page anyway.

Danny handed the book to the Astros dugout the next night, but Ryan wasn’t there. The other players, however, were amazed and started passing it around. “No one else is signing that book!” Danny barked. “Don’t even think about it.” It wasn’t until a decade later that Greg and a friend finally tracked down Ryan, then with the Rangers, next to his car outside Arlington Stadium. He signed on the same page as Dizzy Dean.

So where are Mike Schmidt and George Brett? Tony Gwynn and Ken Griffey Jr.? Were this book its own fairy tale, they’d be right there next to Leo Durocher. But as the Gamble boys became men they became disillusioned with a sport that was having its own growing pains. In 1981, one-third of the season was canceled due to a player’s strike, and the Gambles began drifting further away from baseball. Thirteen years later, another strike wiped out the World Series, hastening the decline of their love of the sport.

“The strikes and all that, it kinda eroded some of the glow in my eyes,” Greg says. And his two kids, a daughter born in 1992 and a son born in ’94, didn’t look at the book with the same wonderment.

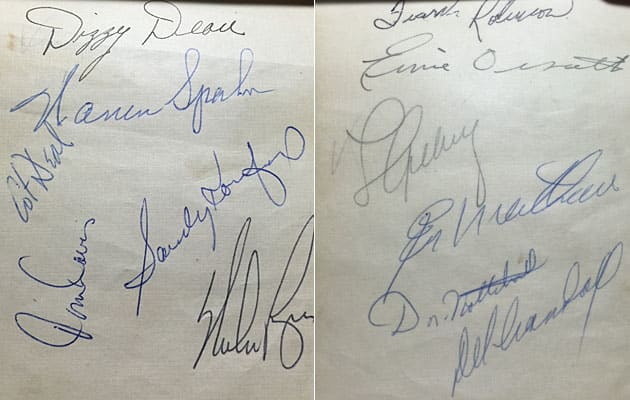

One page of the book (left) features three Cooperstown-enshrined hurlers (Dizzy Dean, Warren Spahn and Sandy Koufax), while another has Lou Gehrig.

Brooks Kubena

Harry Jr. continued to live in Houston until he died in mid-January, and he never set foot in Minute Maid Park, which opened in 2000. Danny moved to Colorado a year after his autograph attempt with Nolan Ryan and never had much contact with the book thereafter. He currently resides in Colorado Springs and thinks there are definitely current players he would like to add. “They’re just not as accessible as they used to be,” Danny says.

Greg took the book with him as he moved to five cities before settling in Nashville in 2008, hoping to pick up more names along the way. In 2002, while working as the District Manager for Ohio and Tennessee for the U.S. Postal Office, he went to a minor league hockey game in Cincinnati to get Pete Rose’s autograph. Charlie Hustle tore his page when he signed. He didn’t ask for payment. Around the same time, Greg added then-U.S. Senator Jim Bunning (R-Ky.) to the page that already had Dean and Ryan.

Bunning’s is the most recent name added to the pocket hall of fame. There have been more recent attempts to get others, but the modern access to players is rarely closer than the knothole view his father once had. A decade ago Greg was urged by his wife, Charisse, to approach longtime Astros star Jeff Bagwell at a mass autograph signing at a sporting goods store, but the line was too long. In 2014, he stopped by Yankees spring training in Tampa in hopes of adding Derek Jeter before New York’s iconic shortstop retired. Greg showed the book to a police officer and asked if he could be escorted to wherever Jeter was. The officer said he’d be fired and Greg would be thrown in jail. “Well, we don’t want either of those to happen,” Greg replied.

So here the book sits. Neither Greg nor Danny are certain what should be done with it; they are only certain that they’ll never sell. But the book’s purpose is more to reflect on its past than to question its future.

Flip through this kineograph of a family’s love for baseball one more time. Trace your finger over the names.

Place it back in the drawer.

And close.