Once a feared slugger, 41-year-old Jason Giambi quietly nears the end

There are now less than six weeks remaining in the baseball season and -- in all likelihood -- in the careers of two of the best hitters of the last couple decades.

One of them, Chipper Jones, has spent this season enjoying one long retirement party -- receiving standing ovations, making an emotional All-Star appearance and writing a column for the back page of Sports Illustrated.

The other has played out the year with no such fanfare. His career statistics aren't that far off Jones' -- 1,405 RBIs to Chipper's 1,621, a career OBP of .403 to Jones' .401, but the similarities end there. The 40-year-old Jones is a beloved figure. At 41, Jason Giambi is a survivor.

On Tuesday, just after 4 p.m., Giambi walked into the visitor's clubhouse at AT&T Park in San Francisco wearing faded jeans and a zip-up hoodie. His hair, once scraggly and dark, is now cropped short, the gray rapidly encroaching on the brown. His ruddy face is covered with a motley silver beard. His body, once so top-heavy that he resembled a New Yorker cartoon come to life, the caricature of an overstuffed slugger, has returned to its natural proportions. Seated at his locker, cheeks red from the sun, he looked less like a superhero athlete and more like the last guy at the bar in Santa Monica at 1 a.m. on a Thursday night.

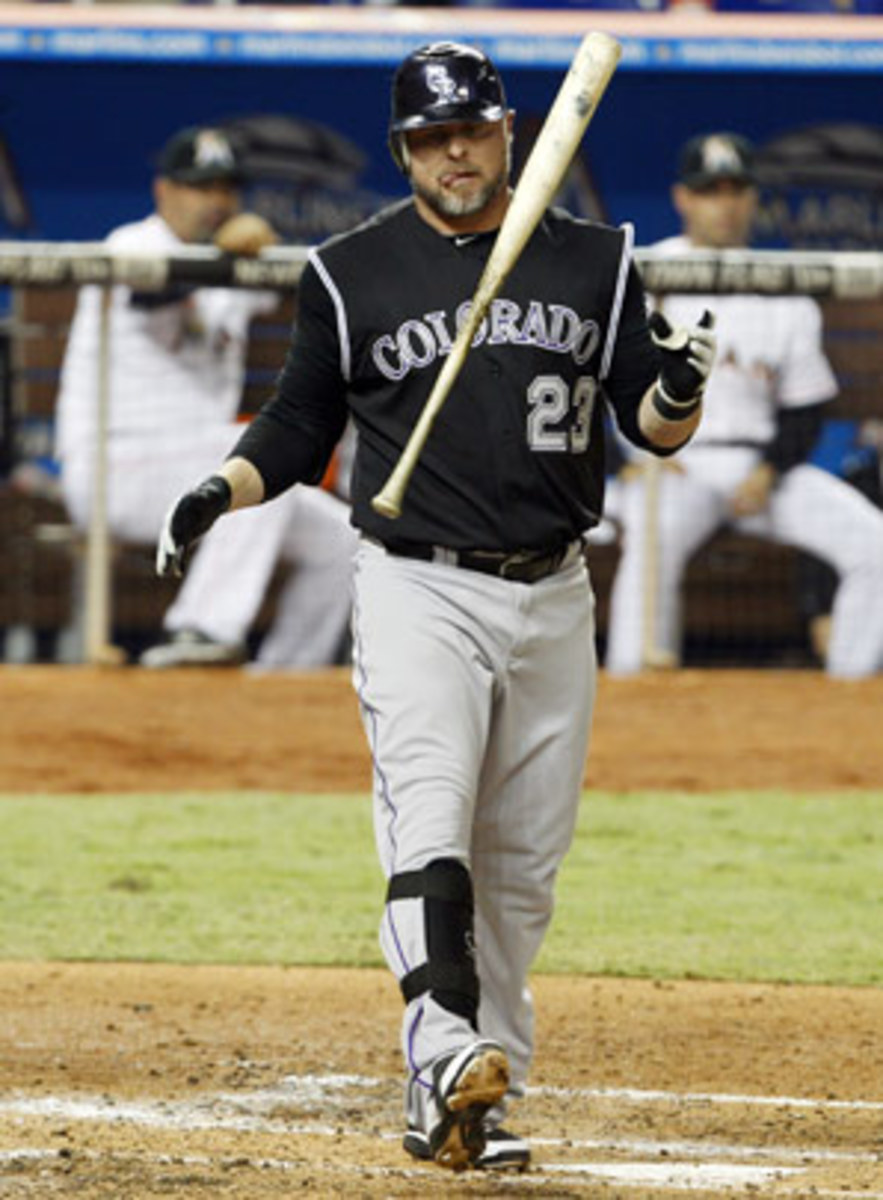

It has been a long, quiet season for Giambi. Now strictly a pinch-hitter, he plays for a woeful Rockies team that is 30 games below .500 and, as a result, has embraced a youth movement in the season's waning months. Entering Friday, it had been 19 days since Giambi's last hit. The man with 429 career home runs hadn't gone deep in more than four months.

This is not how anyone expected him to go out. Giambi won the AL MVP in 2000, led the league in OBP three times and OPS twice. Larger-than-life, he was the leader of the frat house A's, the running mate of Mark McGwire, a teammate of Jeter and A-Rod, and good friends with Michael Jordan (the two played against each other in the Double A Southern League). He also was, and remains, an enduring icon of the steroid age, one of the last home run kings of his era still playing. Most of the other anti-heroes have either retired or slunk away: Bonds and Sosa, Palmeiro and McGwire, Clemens and Juan Gonzalez

These days, he lives for small moments: a late-inning RBI opportunity, one at-bat in a homestand. Most games, he watches the action in the dugout or clubhouse until the fifth inning. Sometimes young players like Dexter Fowler and Jordan Pacheco come to him between innings to discuss their at-bats. He'll talk to them about reading pitchers -- see how he threw you a slider on a 1-0 count last time, then went fastball this time? Other times they come to talk about life. As Giambi says, "Sometimes in this game you don't need a coach, you need a psychologist."

Around the sixth inning, he starts preparing in earnest, hitting off a tee and taking soft toss. By the eighth, he'll recruit a strength coach to throw him some BP in the cage. And then, feeling mentally and physically ready, he waits and hopes. On Monday night, Rockies manager Jim Tracy called on Giambi with two outs in the ninth and Colorado trailing 2-1. San Francisco's lights-out righty, Sergio Romo, came in and unleashed four sinkers and a change-up. Giambi struck out swinging to end the game. "It's a tough job," Giambi says. "When you're successful you ride the high for a bit. If you don't get it done then you have to think about tomorrow."

Ideally, Giambi says he would like to play next season, but he understands that might be unlikely. "Can I still get a job?," he said. "I don't know." The Rockies have approached him about becoming a hitting coach, he says, and maybe one day managing, but he's not ready to consider that yet. For now, he continues to play because he still loves the game, and because he feels his one great skill --power -- remains. And indeed, when I asked Romo about pitching against Giambi, the pitcher nodded in deference. "That's an MVP right there and you can't forget that," Romo said. "Much respect."

Respect. That's also part of why Giambi still plays. In 2007, he told USA Today, "I was wrong for doing that stuff. What we should have done a long time ago was stand up -- players, ownership, everybody -- and said, 'We made a mistake.'" In the years that followed, it would have been easy for Giambi to fade away under the scrutiny, or when his performance slipped and he hit .193 with Oakland in 2009. He had made plenty of money, had nothing left to play for.

And yet here he is. Now, at 41, Giambi has an 11-month-old daughter named London Shay. When I asked what he'd like people to say about her father when she's 10 years old, he stopped for a moment. "Wow ... I would love for them to say, 'One time in his career, he made a mistake but he worked really hard and got his honor back and he was honest,'" Giambi said. "I think that's the most important [thing]. I've been on top of the world in this game, I've won the most valuable player, and I've been in the gutter in this game. But I'm still here."

As he spoke, four nearby Rockies teammates played a game of hearts, while others watched NFL highlights. Troy Tulowitzki, out most of the season with a groin injury, sat glumly in his chair, staring off into the distance. Down the hallway, moments later, Colorado hitters took cuts in the indoor batting cage while pregame rituals played out on the field. Giants players cycled through bunting practice, the smell of roasting hot dogs wafted through the grandstands and, behind home plate, a stooped usher used a spray bottle and a rag to wash down the seats in the first row. The late afternoon sun illuminated the leftfield bleachers. It was a great night to be at the ballpark.

Five hours later, in the seventh inning, with tens of thousands of fans on hand, a 41-year-old man would be called to pinch hit with the bases loaded. The PA would announce his name and Giambi would step in. Realistically, the chances of him turning on a pitch from the lefthanded Jeremy Affeldt and launching it into McCovey Cove would be slim, and indeed he would end up hitting into a double play.

But in that moment, under the lights, standing at the plate, waiting for the pitch, all that would matter was that he was still there, still feared. Still part of the game.