Marvin Miller's glaring omission from Hall of Fame continues

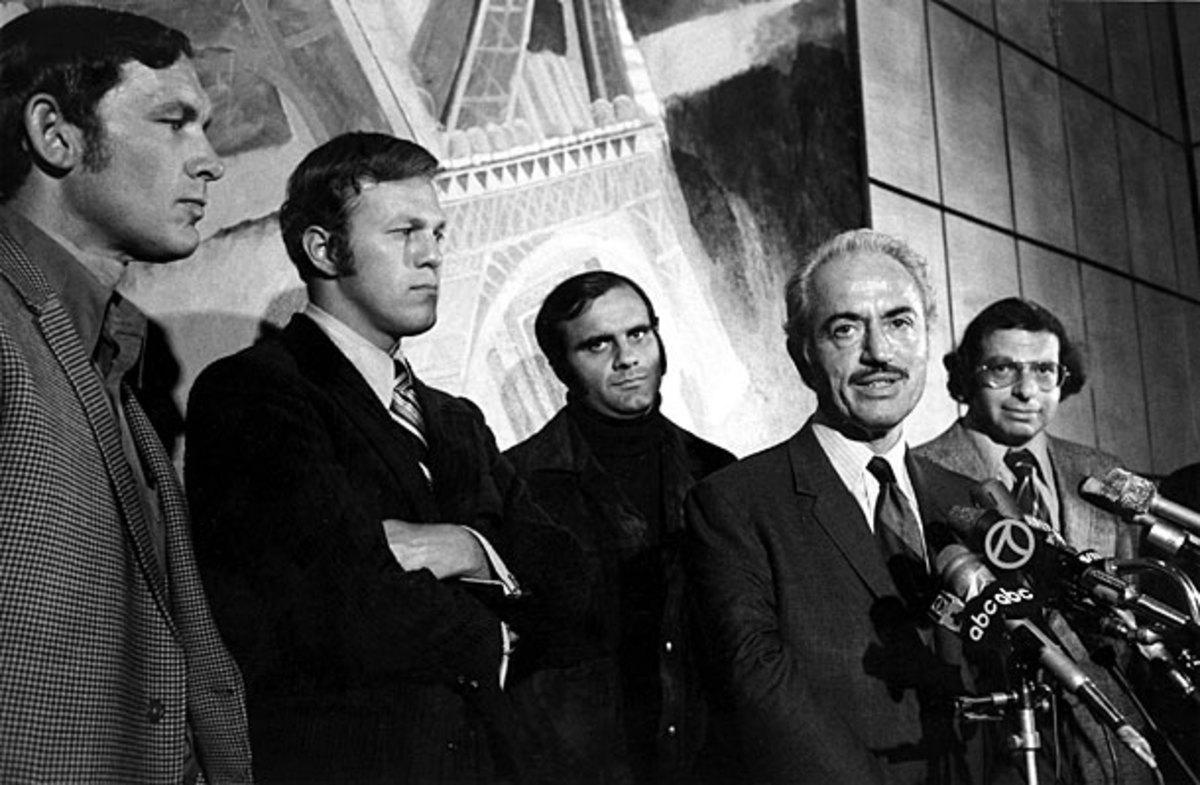

Some feel Marvin Miller (fourth from left) did more to change the game than any of the players he represented. (AP)

You have reached your limit of 4 premium articles

Register your email to get 1 more

During this Hall of Fame election cycle, much discussion has centered around how the crowded BBWAA ballot makes it difficult for any candidate to gain the requisite 75 percent necessary for election. The same can be said for the Expansion Era ballot, the voting results of which were announced on Monday morning. The three managers elected — Tony La Russa, Bobby Cox and Joe Torre — were hardly the only deserving candidates from among the 12-man slate. Marvin Miller, the former executive director of the Major League Baseball Players Association, not only has arguably the strongest case of any individual outside Cooperstown but the strongest case of any non-player in the game's history.

From among the remaining eight candidates, one can also make a good case for owner George Steinbrenner and solid ones for manager Billy Martin and catcher Ted Simmons. If that seems like a ridiculously high number of qualified candidates, it's in part because the old iterations of the Veterans Committee failed to elect anyone in 2003, '05 or '07, contributing to a backlog. All of those unelected candidates this time around received six or fewer votes from the 16-member panel, which elected Cox, La Russa and Torre unanimously but otherwise did not elaborate further on the individual totals. Via the rules for election, voters were allowed to select up to five candidates, so the math says that 32 slots were available for the nine non-unanimous ones; thus it's easy to see how none failed to receive a consensus.

Miller's exclusion from the Hall of Fame may have been his dying wish (he passed away in November 2012, at the age of 95), but it is nonetheless a travesty, a mark of shame on the institution and the various iterations of the Veterans Committee that have bypassed him. His impact upon the game is inarguable; in 1992, former Dodger announcer Red Barber called him one of the three most important figures in baseball history, along with Babe Ruth and Jackie Robinson. As executive director of the union from 1966 to 1982, he oversaw the game's biggest change since integration via the dismantling of the Reserve Clause and the dawn of free agency, thus shifting the century-old balance of power from the owners to the players. The Reserve Clause, which bound players to teams indefinitely, was effectively a system of indentured servitude.

In addition to securing the players the right to free agency, Miller brought them the rights to collective bargaining, impartial arbitration of grievances, representation by an agent to negotiate on their behalf and the ability to reject a trade after accruing enough major league service. His leadership also brought the players the system of salary arbitration and substantial increases in the pensions of retirees. During his tenure, the average salary of a major league player rose from $16,000 to over $250,000, and the MLBPA became the strongest labor union in the country.

Petty politics have prevented Miller from receiving proper recognition via enshrinement in the Hall of Fame, both during his lifetime and since his passing. From his retirement to the 2001 expansion of the Veterans Committee, which granted the vote to every living Hall of Famer as well as the surviving Ford C. Frick Award and J.G Taylor Spink Award winners (the broadcasters and writers), Miller didn't appear on a single ballot. Influential players from the pre-union days resented the high salaries and freedom of movement that modern players enjoyed, and even the most historically-minded writers on the committee disagreed on his eligibility.

Once Miller finally got a spot on a ballot composed of executives, umpires and managers in 2003, he received just 43 percent of the vote; ironically, many of the players whose careers he helped the most, such as Reggie Jackson, wouldn't return the favor. With the eventual support of Jackson and others, Miller rose to 63 percent the next time around, in 2007, but when the process reverted to a 12-member panel in 2008, he received just three votes while his longtime adversary, commissioner Bowie Kuhn, was elected.

That panel was a stacked deck, lacking a single player from the post-Reserve Clause era and stocked with seven owners and executives linked to either that era or the late-1980s collusion scandal. So frustrated was the 91-year-old Miller that six months later, with his candidacy not set to be reviewed for another 18 months, he took the unprecedented step of asking the Hall of Fame not to include him on another ballot, saying in a letter to the BBWAA (which only had partial input on the process), "I find myself unwilling to contemplate one more rigged Veterans Committee whose members are handpicked to reach a particular outcome while offering a pretense of a democratic vote." Like any great labor leader, Miller knew how to count votes before an election was held, and he knew when he didn't have them.

When I interviewed Miller for Baseball Prospectus shortly after that release, he vowed not to show up for induction if the Hall went against his wishes and the VC elected him, referencing both Civil War General William Tecumseh Sherman (who refused to run for president; "If elected I will not serve…") and comedian Groucho Marx ("I don’t care to belong to any club that will have me as a member.").

Since then, Miller has been bypassed three times, and the process has changed yet again. He received seven of 12 votes (58 percent) for the 2010 ballot and then 11 out of 16 — a single vote shy of election — from the Golden Era panel (covering 1947-1972) the following year. Notably, White Sox owner Jerry Reinsdorf, a collusion kingpin and anti-union hardliner, was on the committee as part of a four-executive bloc that required Miller to run the table among the other 12 voters, assuming they all passed on his candidacy. Reinsdorf was on this year's panel, as was Andy MacPhail, whose father and grandfather were executives from the Reserve Clause era. Six Hall of Fame players, five of whom — Rod Carew, Andre Dawson, Carlton Fisk, Paul Molitor and Phil Niekro — benefitted from free agency, were part of the panel as well.

To be fair, Miller's children have reiterated his position since their father's passing. Son Peter Miller wrote in 2012:

“No one in our family will attend or speak at any HOF ceremony regardless of the outcome of the HOF vote. It’s important for union members and the media to understand why, so that the story does not get misrepresented as ’sour grapes,’ personal pique, or anything of the sort.

It's perfectly understandable that Miller's family would want their father's wishes to be honored, and to be fair, it would have looked every bit as bad for the committee to elect Miller in their first opportunity after his death as it did when Ron Santo was elected in 2011, one year and two days after his passing. Even so, I believe he will get in eventually. It may take until the next cycle (three years from now) for a more modern set of former players, managers and executives to get it right, or it may take a generation, but he'll get his plaque in Cooperstown. When he does, both his accomplishments and the stain of the institution's failure to honor him during his lifetime will be part of the story.

As for the others who had solid cases, Steinbrenner, the principal owner of the Yankees from 1973 until his death in 2010, is the most prominent. Certainly, he spent much of his tenure as a cartoon villain, suspended from baseball by commissioners not once but twice, hiring and firing 21 managers in his first 20 years, burning through general managers at a similarly absurd clip and shooting his mouth off in the media on a routine basis. Even so, he was undeniably one of the game's foremost power brokers and a visionary when it came to surviving the dismantling of the Reserve Clause and the introduction of free agency.

Time after time, Steinbrenner used his team's financial might to best advantage and put his money where his outsized mouth was. His teams won 11 pennants and seven World Series during his tenure. For all of his notorious bluster and itchy trigger finger, he was quick to give players, managers and executives in his organization a second (or third, or fourth…) chance, just as he had received. In the end, he restored luster to the Yankees franchise, turning it into the most valuable property in professional sports, worth an estimated $1.6 billion at the time of his passing.

The fiery Martin, best known for his five stints with the Yankees, also managed four other teams as well during a career of 16 (sometimes partial) seasons spread out over 20 years from 1969-88. During that time, he compiled a 1,253-1,013 record, good for a .553 winning percentage, the 14th highest among managers with at least 2,000 games. Of the managers above him, 12 are in the Hall of Fame including Cox, with the recently retired Davey Johnson the lone exception, though Cap Anson is there more for his playing than his managing. Meanwhile, Martin's 240 games above .500 ranks 20th, well ahead of many Hall of Famers.

Martin took his teams to the playoffs five times, winning two pennants and one World Series. He was a strategic genius whose specialty was in turning teams around on a dime, but he invariably wore out his welcome, triggering verbal battles with owners and players (most notably Steinbrenner and Reggie Jackson), some of which spilled into actual brawls. Alcoholism was a factor in his notoriously tempestuous nature. It's not surprising that he wasn't elected on a slate that included three more successful (and more stable) skippers who were contemporaries. It's possible that he'll never make it to Cooperstown, but I do think he should be in.

As for Simmons, he was an eight-time All-Star catcher known more for his bat (.298/.366/.459, 118 OPS+, 2,472 hits, 248 homers) than his glove. He ranked among the league’s top 10 in batting average six times, was in the top 10 in on-base or slugging percentage nine times and was among the top 10 in position player WAR five times. Behind the plate he was an adequate backstop, maligned during his era but essentially average via Total Zone (-8 runs career). In terms of JAWS, he ranks ninth at the position, 0.6 below the overall standard but ahead on peak score.

Simmons went one-and-done on the 1994 BBWAA ballot, receiving 3.7 percent of the vote. His candidacy was hurt by his struggles over his final eight seasons after being traded away from the Cardinals , where he spent his first 13 years (1968-80). Notably, he was sent to Milwaukee by manager/general manager Whitey Herzog, a member of this year's panel. His failure to get even five percent of the vote two decades ago may have also owed something to do with lingering resentment over the fact that in 1972, in the wake of former teammate Curt Flood’s challenge to the Reserve Clause, he became the first playing holdout in baseball history, playing well into the season without a signed contract before the Cardinals gave in to his demands.

Miller, Steinbrenner, Martin and Simmons would have made worthy additions to this Cooperstown class along with Cox, La Russa and Torre. It's Miller's exclusion that will continue to resonate the most, however. Without him, the Hall of Fame is simply incomplete.

This article has been updated to include the number of candidates each voter could select.