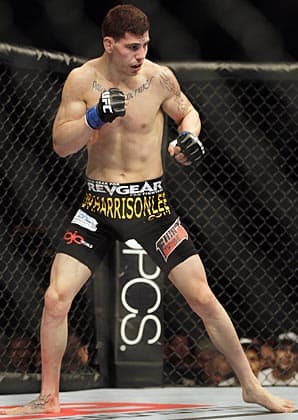

Flyweight Jared Papazian fighting for his survival in the UFC

Jared Papazian will try to improve on his 14-8 record when he takes on Tim Elliott in the Ultimate Fighter Finale card.

Mark Humphrey/AP/SI

His nose was broken, his head concussed, and from behind the blood clouding his eyes, 15-year-old Jared Papazian could see 40 people or so surrounding him. Some of the spectators gaped, some winced as he writhed on the sidewalk outside the Woodland Hills, Calif., AMC movie theater, but none, he says -- offered to help as a group of 10 guys pummeled him.

The fight stemmed from an incident a month earlier, when Papazian caught a high school football teammate rifling through other people's lockers. Papazian confronted him, and a month later found himself on the receiving end of the teammate's older brother's -- and friends' -- fists and feet, punched, kicked and collapsing.

"It was the worst fight I've ever been in," Papazian said. "I was fighting for my life."

Now 24 and nearly a decade removed from the beating, Papazian finds himself fighting for a life of a different sort -- that of his professional career. In an only-in-the-UFC paradox, Papazian is simultaneously one of the most promising prospects in the flyweight division and on the verge of getting cut by the organization. Two consecutive losses his 14-8-0 record make his Saturday bout against Tim Elliott (8-3-1) on The Ultimate Fighter Finale card in Las Vegas a must-win for the West Hills, Calif., fighter. A third loss would most likely mean he'd be cut from the UFC. But Papazian vows not to go down without another Fight of the Night-worthy performance.

After getting jumped outside the theater, an embarrassed Papazian found a martial arts gym near his home, intent on improving his fighting skills and seeking retribution. "[The fight] really messed me up," he says. "I wanted to get revenge. That was my goal. But it didn't end up that way. I ended up loving the passion for the sport." The discipline of martial arts training heightened his fighting abilities but tempered his anger, channeling it to an art form instead of a street brawl. Soon, he had professional fighting on his mind.

Papazian launched his pro career in 2008 with a unanimous decision win over Josh Chaves. He followed his debut win with another victory but then stumbled and began a maddening fight pattern of winning two in a row, then losing two in a row. A year after his debut, Papazian floundered, stuck with a 4-4 record and a track record in which he'd never fought for the same promoter more than once.

"I was pretty much going downhill in my career. I had no one really watching me and picking my fights and watching my training, the things I needed as a fighter. I was pretty much doing what I know myself and that's not always best," Papazian said.

But three years ago, Darin Harvey, owner of Fight Tribe Management, whose client list includes Ronda Rousey, stepped into a gym for his own kickboxing workout. Harvey spotted Papazian training and offered to grapple with the fighter who showed as much in heart as he lacked in technique. Almost instantly, Harvey, also an amateur martial artist himself, had Papazian in an armbar. It would be the fighter's most fortuitous loss. Ten minutes after Harvey left the gym, he called Papazian and offered to represent him.

Papazian calls it a threshold moment in his career. Harvey enlisted coaches like Alberto Crane of Crane's Gracie Barra School and striking coach Edmond Tarverdyan to perfect Papazian's already powerful punching. By 2010, he reeled off five consecutive wins and by June 2011, claimed the King of the Cage 135-pound crown. He successfully defended his title three months later in a decision over Melvin Garcia. Lesson by lesson, remnants of the kid beat up outside the movie theater dissipated.

As Crane told The Los Angeles Daily News last January, "To be honest, [Papazian] was kind of a punk. One thing for me was he had to change his attitude, and his attitude changed. . . The one thing I noticed was he never missed a practice and he always gave his best, training hard, week to week, month to month. . . I cornered his fights and I saw what he was made of. He was a fighter and he was a fighter in his soul."

Those are the same characteristics that have made even his toughest losses exhilarating. Last January, Papazian accepted a bout against the well-regarded Mike Easton on short notice for the UFC's debut card on FX. The three-round ruckus ended with a narrow decision to Easton and outrage on Twitter. So many fans tweeted UFC President Dana White their displeasure that the Papazian-Easton fight didn't earn Fight of the Night honors (not to mention the bonus money fighters receive with the distinction) that White cut both fighters checks.

Papazian promises the Elliott bout will up be for Fight of the Night honors, too. It has to be. "It has crossed mind this is my last shot. It's crossed my mind that I might get cut," he said. "I'm just going to treat it like any other fight. . . If I leave everything in the cage, then I'll be happy with anything."

The fighter says he's improved his wrestling, fortified his striking. And as if he needed any extra motivation, he's dedicated the fight to his grandmother, Marlene Koppenhaver, who died last August at 78. His trunks and his banner will bear a remembrance to her.

"I'm going to knock him out," he says. "I'm not going to leave it the judges. It might cost me career."

But no matter the outcome of the fight or his contract status, Papazian knows this much: "I'm ¬not going to quit after this. It's my passion, my love and I am one of the best guys in the world."

And to think, he might not have ever known it if it hadn't have been for the worst fight of his life.