Impoverished youth, mother's struggles fuel dos Santos' stellar career

At age 11, Junior came home to find his mother weeping at that same table, her head in her hands. She'd purchased the previous month's groceries on credit and upon receiving her wages, had realized she didn't have enough to pay back the debt, let alone get more groceries for the next couple of weeks.

By then, Junior's alcoholic father had gone for good, putting an end to the arguments with Junior's mother and the periods where he'd leave for days and weeks at a time without a word. Sebastian was no longer welcome at his wife's home, which meant Junior and his siblings wouldn't get to see their absentee father often.

Junior's mom had gone to work as a cleaning lady in the furniture factories in Cacador, a small, timber-industry town outside Santa Catarina in the south of Brazil, where Junior was born and spent his early years. It was heavy labor and long hours on her feet for little pay, and Junior's mother had no choice but to leave her three children at home alone, often to fend for themselves.

"Her hands were completely scarred from these harsh, abrasive chemicals that she used. For a woman, that's a very difficult thing, but I just remember her not caring about that," said dos Santos through his translator and manager Ana Claudia Guedes. "She only cared about providing for us."

Junior decided early on that he was going to become somebody -- somebody who would make a nice, tidy living to someday care for the mother who'd disfigured her hands to put food on the table.

You see, Junior was born with something in short supply in Cacador, where families were grateful when they could scrounge enough money together for food and rent. With the hardships of poverty all around him, Junior was born an optimist.

Junior was going to be somebody. The question was just how he'd do it. He once told his mother he would study to become a doctor, so he could someday relieve the pain she had from the varicose veins that protruded up and down her legs.

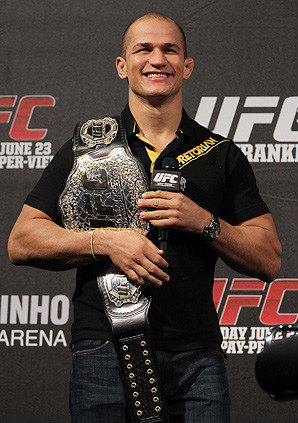

Dos Santos never made it to medical school, but he found another path to success -- through professional sports. The 28-year-old UFC champion already has one promotional record to his name for the most consecutive wins ever in the promotion's heavyweight division (9). Dos Santos (15-1) will try to stretch that record to 10 at UFC 155 this Saturday in Las Vegas, rematching Cain Velasquez (10-1), the former champion he usurped more than 13 months ago.

There were a lot of jobs on the road to UFC gold, and when Junior was old enough by Brazil's standards, he went to work to help support his family. He picked beans and apples, delivered newspapers, assisted a mason, apprenticed with a truck driver, and sold popsicles and fruit in the streets.

At age 17, Junior dropped out of high school one year early to take a job loading furniture into trucks for transport, but ever the optimist, he had a plan in place.

At age 18, all young men in Brazil are required to enlist in the military; dos Santos saw this as his opportunity to break away. "I'd dreamed of having a military career and I'd wanted it badly," he said. When he was of age, dos Santos pulled together money he didn't have to travel to the bigger city of Curitiba for his medical examination.

The examinations were conducted in large groups, and the young men lined up naked as a physician and dentist worked their way down the cue. If one of the doctors asked you to get dressed, you knew you'd been rejected for some reason. The dentist stopped in front of dos Santos.

"I was missing a tooth that had cracked and gotten infected, then fallen out, so they told me to put my clothes back on. I was devastated," said dos Santos. "I went there thinking the military was going to be my way out, the way to improve my life. "

Dos Santos found a $10 hotel room for the night, then headed back to his job in Cacador loading trucks, his eyes always open for the next opportunity to present itself. He didn't wait long; just a few months later, dos Santos left his mother and siblings for the northern city of Salvador in search of better work. He got a job in a fancy restaurant as a waiter and was at the door greeting and seating customers when his future wife, Vilsana, walked in. They exchanged glances as another waiter served her and her companion. At the end of the meal, Vilsana insisted that only Junior could collect the bill. She'd left her phone number on it for him.

Vilsana owned a toy shop that needed a manager, so Junior became the most popular adult in the neighborhood, a purveyor of dolls, model cars and board games. He demonstrated the toys, wrapped them up and sold them to the local parents and their children, and like most other things, he did it with a smile. The store flourished for a few years, so much that Vilsana and Junior added two more in that time. But at some point, business began to slow and the couple knew it was time to sell the small chain of stores.

Standing behind a counter playing with toys all day hadn't done much for dos Santos' physique and his 6-foot-4 frame had put on a few more pounds than he felt comfortable with. He walked into a local gym to work out, but floated over to a Brazilian jiu-jitsu class in session. He joined the next class, taught by black belt Yuri Carlton, who after one month of instruction, invited Junior to join his nightly MMA classes. Carlton also introduced Junior to Luiz Carlos Dórea, Brazil's national boxing team coach and a trainer to MMA fighters like Anderson Silva and Lyoto Machida at his Academia Champion gym. Thus began his MMA career.

"I took serious beatings," said dos Santos. "I was basically a punching bag for far more skilled fighters. I would leave the gym at night and they wouldn't expect me back the next day. But I'd be back the next day and the day after that."

Giving up was never an option, he said.

"I remember when I first started going to those classes, my wife told me that if I believed in it, that I should do it and go for it and give it my all," he recalls. "She was my angel. She believed in me. For me, it was a one-way decision. This was a one-way street. There wasn't any going back."

Coaches Carlton and Dórea saw great potential in Junior. It was rare for a heavyweight to move as efficiently as dos Santos did. Junior showed a particular talent for boxing and his speed afforded him the time to develop into a thinking fighter who could pick and choose his shots after careful study of his opponent's patterns and tendencies. Dos Santos built up an 8-0 record on the local boxing circuits before making his MMA debut in July 2006 with a first-round knockout victory.

Shortly after his debut, Junior got word that his father, an industrial mechanic by trade still living to Cacador, had fallen ill. Years of daily drinking had caught up with Sebastian (High-proof cachaca was his drink of choice) and his health had eroded. Eventually he had a stroke, was admitted to a hospital and never left. Junior now lived nearly 1700 miles away, so he spoke with his father on the phone until the day his father suddenly stopping talking altogether.

Before the silence, Sebastian had given his daughter, sitting bedside with him, a message to share with her brothers.

"He said to tell me that you pay for your sins in life," said dos Santos. Sebastian died a few days later.

"When my mother called to tell me he'd died, it was just frustrating. It was hard," said dos Santos, who was then 23 years old. "My career had started and I was getting ready for my second professional MMA fight."

Junior also didn't have the means to make it down to Cacador in time for his father's funeral, which was held the day he died, as most bodies are not embalmed in Brazil. Junior remembers his father as a calm, mellow man, who worked hard to support his family while he could.

"One of the things I regret the most is that I never had a chance to show my dad who I became," said dos Santos.

Dos Santos' father would have been very proud to see the dedication and care his son has given his craft. From 2006 to 2008, dos Santos complied six wins and one loss, mostly from TKO stoppages. He made his Octagon debut at UFC 90 in October 2008, crumbling the much more experienced Fabricio Werdum (16-5-1) with a barrage of punches in a little over a minute. In the next two years, dos Santos systematically took out a young Stefan Struve, a past-his-prime legend in Mirko "Cro Cop" Filipovic, and contenders like Roy Nelson and Shane Carwin.

Dos Santos got his title shot against champion Velasquez headlining UFC on Fox 1, the promotion's first live event on broadcast television, in November 2011. It lasted only 64 seconds, but became the most watched fight in MMA history with 8.8 million viewers. Dos Santos, who'd torn his meniscus only 11 days earlier, won by technical knockout. He doesn't expect the rematch to follow its predecessor, though, now that Velasquez's wrestling skills are back in play coming off ACL recovery.

"For me, that first fight was perfect," said dos Santos. "I had an injury and was looking for a quick knockout. I've watched a couple of interviews he's done for this fight and he seems very hungry, very motivated. I expect a different fighter."

As reigning champion, dos Santos defended his title last May and became the third MMA fighter, along with fellow champions Anderson Silva and Jon Jones, to secure a coveted Nike sponsorship.

But as earnest as he is in the cage, the always upbeat dos Santos doesn't take himself too seriously out of it. He breaks into song constantly, chirping everything from Katy Perry to Adele. He mugs for the cameras, making it nearly impossible for the UFC production team to capture his menacing, eye-brow-raised introductions that play at the top of pay-per-views.

Dos Santos also likes to horse around, somewhat of a hazardous undertaking for a man with more physical strength than he seems aware of. Two training partners in dos Santos' current camp have lost teeth -- and we're not talking from sparring. One was the recipient of something dos Santos called a "friendly punch;" the other ate an elbow during a handshake gone awry. Junior's training partners have taken to calling him "Felicia," in reference to a little girl cartoon character who throws and breaks all of her toys.

In other words, dos Santos is enjoying his moment for however long it lasts. His UFC stardom has brought him $200,000 fight purses, with more revenue coming from bonus awards and sponsorships. It's been enough to pay for his mother's leg operation and to set her up more comfortably. He's reached out to help his cousins, nieces and nephews and other relatives financially, as well.

"I've lived in tough situations and I don't ever want to go back to that," dos Santos said. "I get strength from those memories that I turn into dedication and will power."

It's a motivation that's fueled him well so far. Past opponents speak of dos Santos' uppercut the way boxers used to marvel at Mike Tyson's: you don't want to be in the way when he swings. And with that unprecedented nine-fight win streak in the UFC's heavyweight division, dos Santos is at the point in his career where he can start to build a meaningful legacy.

There are a lot of things dos Santos loves about fighting, but most of all, he loves to win. In that moment, the harder times he experienced to get there seem worth it.

"I love when my arm is raised in the Octagon and people are shouting my name and cheering," said dos Santos. "I love the sensation that they appreciate me and that they validate my work and I feel like I'm somebody. I made it. I became somebody."