Can a Moneyball Maven Fix the Browns?

Tom Verducci is Sports Illustrated’s lead baseball writer and an on-air analyst for MLB Network and Fox Sports.

Most of us, after we finish a good book, simply close the cover and put it away. When Paul DePodesta finished a good book last summer on how technology will change health care, he excitedly dashed off an e-mail to the physician who wrote the book, which led to a three-hour lunch with the author, which led to a featured speaking role for DePodesta at a “Transforming Medicine” conference, which led to his hiring three weeks ago as an “assistant professor of bioinformatics” at a digital medicine institute. The role was a side gig to his day job as vice president of player development and scouting for the New York Mets.

While DePodesta was reading The Patient Will See You Now by Dr. Eric Topol, Jimmy Haslam, who was entering his third full season as majority owner of the Cleveland Browns, was criss-crossing the country in search of his own cutting-edge information. In what amounted to a year-long “best policies” tour, Haslam visited some of the brightest minds in professional sports to learn about their systems and practices. He met with executives from baseball teams such as the Los Angeles Dodgers, St. Louis Cardinals and Cleveland Indians and basketball teams such as the Oklahoma City Thunder.

On Tuesday, the inquisitive minds of DePodesta and Haslam officially came together when the Browns announced the hiring of DePodesta as their “Chief Strategy Officer.” DePodesta will report directly to Haslam.

To the uninformed, the takeaway from the hiring went something like this: “Hapless Browns hire baseball’s Moneyball stat geek as football guru.”

Hey, why let a little information get in the way of good snark, right?

“Paul is the smartest person I’ve ever been around. If the owner gives him enough runway, in a short time Paul will make an impact.”

But when you actually bother to get beyond the Johnny Moneyball jokes, you begin to understand that the Browns—yes, the Browns—after extensive research have hired a bright analytical mind, a former college football wide receiver, an asset that plays well in today’s data-rich business environment, including even (or especially) in the macho corner of sports known as professional football.

“From the standpoint of raw intelligence, Paul is the smartest person I’ve ever been around,” said Josh Byrnes, vice president of baseball operations for the Dodgers, who worked with DePodesta in the Indians’ front office. “From a strategizing viewpoint, he’s brilliant. If the owner gives him enough runway, I have no doubt in a short time Paul will make an impact.”

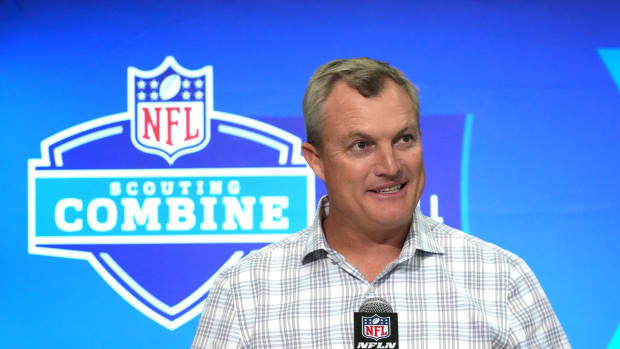

Haslam has been looking for answers, mostly in vain, as Browns owner.

Nick Cammett/Diamond Images/Getty Images

The first thing you have to do is get out of your head Jonah Hill’s Peter Brand character in the Moneyball movie. Overweight, unathletic and socially awkward, Hill played a character based on DePodesta and intended to use DePodesta’s name. But the role was such a sloppy, inaccurate caricature that DePodesta insisted his name be removed from the script. (DePodesta actually was a letter-winner on the 1994 Harvard football team as a wide receiver, listed at 5-9, 160 pounds.)

Moneyball is the well told if selective narrative of how the Oakland Athletics used analytics—much of it driven by DePodesta/Brand—to gain an edge on their competition, never mind that Mark Mulder, Tim Hudson and Barry Zito, three aces in their prime, were starting about 100 games a year for the A’s. Oakland hired DePodesta from Cleveland, where analytics had been in full bloom, and where the franchise was a hothouse of front-office talent.

From 1998 to 2008, the Indians employed 10 current or future general managers—John Hart, Dan O’Dowd, Mark Shapiro, Byrnes, DePodesta, Neal Huntington, Chris Antonetti, Ross Atkins, Mike Hazen and Mike Chernoff—as well as past and future managers Bud Black, John Farrell, Terry Francona and Buck Showalter.

The Indians of the mid-’90s were one of the first clubs to establish sophisticated video advance scouting systems. Around the same time, they expanded their pro scouting system to include more detailed reports on all minor league players, and soon began using statistical analysis to supplement those reports.

In 1998, for instance, Byrnes, then the assistant director of scouting, and DePodesta, then an assistant in baseball operations, used those reports to scout for hidden gems in the minor league systems of other organizations. They found in the Detroit Tigers system a 26-year-old outfielder who had never advanced beyond Double-A and had very little power. They noticed that he did, however, show a consistent knack for getting on base—then an undervalued skill.

The player’s Double-A on-base percentage was .434 on June 24, 1998. That’s when the Indians traded slugger Geronimo Berroa to get pitcher Tim Worrell and this speedy outfielder who was dead-ended in the Tigers system: Dave Roberts. Though Roberts had a tough time cracking the talented Indians’ lineup, he did go on to play 10 seasons in the major leagues, had the most famous and significant stolen base in Boston Red Sox history and was recently hired by Byrnes’ Dodgers to be their manager. (Berroa was out of baseball in three years, having hit just two home runs after the trade.)

After Oakland, DePodesta had a run as Dodgers general manager that lasted only 20 months before he was fired, a four-year run as an executive with the Padres, and his five-year stint with the Mets. One colleague with the Mets, who said he was not surprised by DePodesta leaving for football, described him as someone “always looking for a challenge,” who was “not just a baseball guy.” He characterized him as a brilliant systems analyst who “does not like confrontations,” a trait that may have worked against him in his tenure with the Dodgers.

With the Browns, however, as a football source pointed out, Haslam smartly empowered DePodesta in what has been a chaotic organizational flow chart by having him report directly to the owner. By answering only to Haslam, DePodesta, an NFL outsider, now has unquestioned authority and can designate others to handle day-to-day confrontations. It was not immediately clear if DePodesta would move his family to Cleveland or continue to use the San Diego area as his home.

DePodesta’s first big move will be the hiring of a head coach. Based on the model used by analytically inclined baseball teams, he is likely to hire a coach who may not have much experience but who is comfortable implementing the business practices and systems endorsed if not created by the front office (though not necessarily offensive and defensive schemes). That’s a sharp turn from the old-school football model in which the coach sets the culture. The manager/coach as key conduit rather than majordomo—former Rays and current Cubs manager Joe Maddon is a prime such figure—was a vital component in Haslam’s “best policies” tour.

DePodesta was VP of player development and scouting for the Mets for five seasons.

Paul J. Bereswill/AP

In The Patient Will See You Now, Topol, the director of Scripps Translational Science Institute in San Diego, argued for a very different future in medicine, one in which smartphones replace doctor visits for diagnostic tasks, and big data empowers providers to better treat and even cure disease. According to the Dec. 15 release from STSI, the book resonated with DePodesta because he was “looking to apply his skills and knowledge to a field with global impact.”

The announcement of his hiring was billed as “Moneyball Comes to Medicine.”

Explained DePodesta in the release, “In disciplines as disparate as baseball, financial services, trucking and retail, people are realizing the power of data to help make better decisions. Medicine is just beginning to explore this opportunity, but it faces many of the same barriers that existed in those other sectors—deeply held traditions, monolithic organizational and operational structures, and a psychological resistance to change.” (DePodesta interestingly used trucking— Haslam’s business—as one of his examples.)

Deeply held traditions … monolithic organizational and operational structures … psychological resistance to change … DePodesta might well have been talking about the National Football League.

He knows he will encounter resistance, even if most of it will be external. The information revolution in football is underway, but it lags behind the one in baseball, which is fully populated with types like DePodesta who have long entered the next stage: synthesizing the information with on-field knowledge and observation. Some day, for instance, just as we wonder now why baseball teams used to play their defense straight up for every batter instead of shifting, we might look back and wonder why teams punted away the football so darn much.

Immediately, though, DePodesta’s challenge is not how the Browns play football as much as it is how the organization is structured and how it evaluates, acquires and develops talent in a holistic manner. With his year scouring for information, Haslam understood that his Browns, long a disorganized mess, were in serious need of organizational repair. And when he found his man, he might well have borrowed from DePodesta’s summer reading list to explain to him the challenge ahead: “The patient will see you now.”