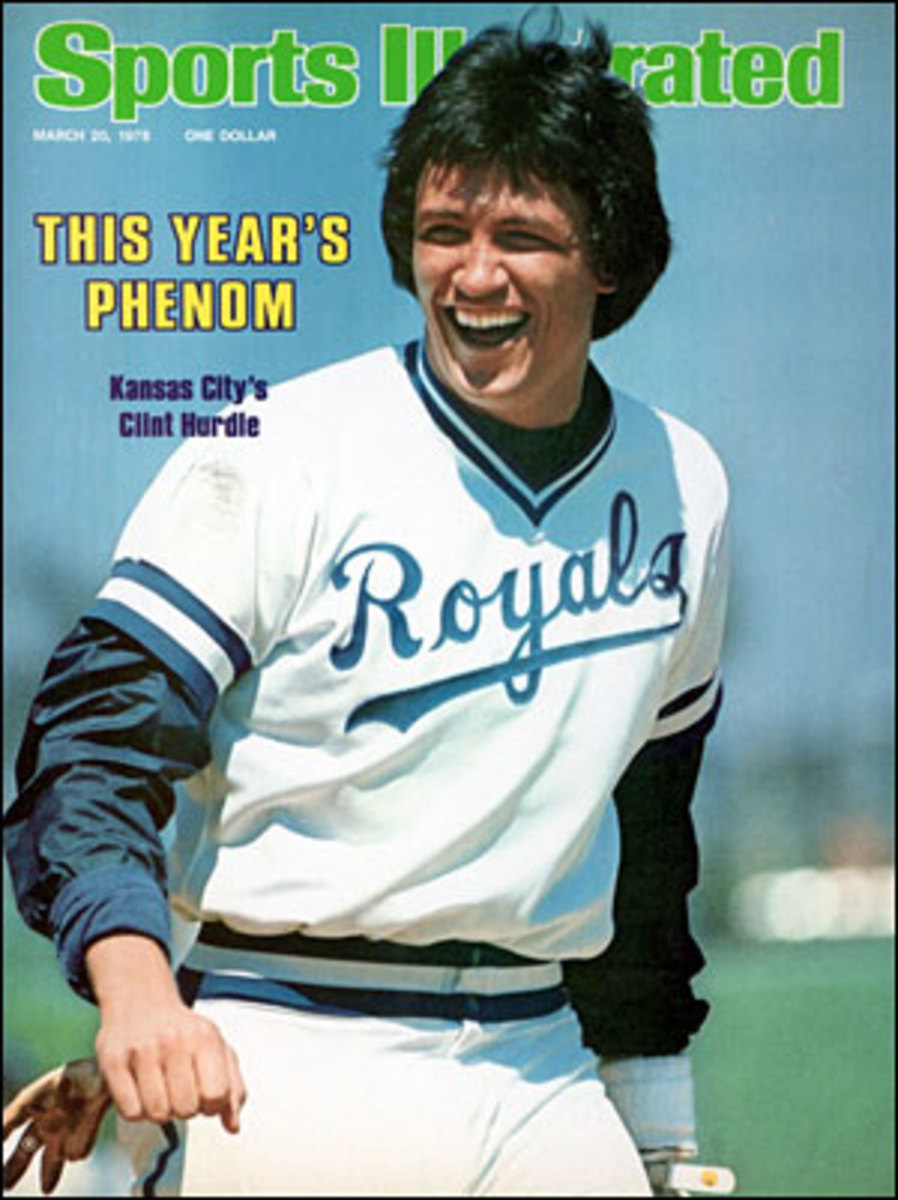

SI Flashback: This Year's Phenom

In 1968 Clint Hurdle was a precocious 10-year-old kid dragging bats for the Cocoa Astros of the Florida State League and playing an occasional game of catch with a promising Astro first baseman named John Mayberry. Now, in 1978, Hurdle is tall, dark, handsome and brash and able to hit a baseball nine miles, and he and Mayberry are together again, this time at the Kansas City Royals' training camp in Fort Myers, Fla. Clint Hurdle, you see, is trying to take away John Mayberry's job.

Hurdle is only one of several rookies given a solid chance to break into a major league regular lineup this season. Not one of them has more confidence than Hurdle, not one has better credentials, and not one faces a more difficult task. The Royals, after all, are not exactly begging for help, and the 28-year-old Mayberry is hardly a liability at first base. Kansas City has won the last two American League West titles, and the slick-fielding Mayberry has averaged 24 home runs and 92 RBIs a season since he was acquired from Houston in 1972.

Like budding flowers and chirping birds, phenoms are a sure sign of spring, but a phenom named Clint does not come along very often. The last was Clint Hartung, a 6' 5" pitcher-outfielder who reported to the New York Giants' spring-training camp in 1947 amid proclamations that he was "an entire ball club in himself." Hartung did make the team, and he showed promise during the 1947 season by winning nine of 16 pitching decisions and batting .309 in 34 games. But by 1950 his pitching days were over, and in 1952 so was his career. He left with a 29-29 career pitching record, a .238 lifetime batting average and 14 home runs.

No one in the Royals organization expects Hurdle to wind up as another Hartung. The very mention of Hurdle's name causes heads to bow and heartbeats to quicken. General Manager Joe Burke calls him "one of the top prospects I've seen in the 17 years I've been in the major leagues." John Schuerholz, the director of scouting and player development, says, "I bubble inside when I think about his potential." Batting instructor Charlie Lau, the maestro behind George Brett's bat, considers Hurdle "the best hitting prospect I've ever seen in our organization." Manager Whitey Herzog rates him "the best player in the minors last year." Even Mayberry concedes, "He has the makings of a great player."

Mayberry would not be so concerned about his job security if he had not made the mistake of having the best year of his career in 1975, when he hit .291 and had 34 home runs and 109 RBIs. Since then his batting totals have fallen off considerably, making him the focal point of criticism in Kansas City. "On this club, anyone batting fifth where John does ought to drive in at least 100 runs," says Herzog. Last year Mayberry had 83 RBIs and a puny .230 batting average.

One thing that has not fallen off, though, is Mayberry's glove work at first base, a skill Hurdle, who has played mostly in the outfield, is not likely to replace. "Without John over there," says Third Baseman Brett, "[Shortstop] Fred Patek and I could have a lot more errors."

Mayberry has been sharing some of his defensive wisdom with Hurdle this spring. "I like Clint, I really do," says Mayberry. "First is a tough position. I don't think I'm hurting myself by helping him because I have confidence in my own ability. I think I can hold on to the position by not trying for the long ball every time and concentrating on raising my average. Last year I was thinking home run as soon as I left the on-deck circle."

If Hurdle does not make it at first base, he could take over in left field, where the Royals would prefer an everyday player with Hurdle's type of power instead of incumbents Tom Poquette and Joe Zdeb, who platooned in left last year. Poquette and Zdeb both hit over .290, but they also had only two home runs each. And Poquette and Zdeb have another Royal rookie to worry about--Centerfielder Willie Wilson. If Wilson, who hit .281 and stole 74 bases at Omaha last season, beats out veteran Amos Otis for the job in center, Otis may well become the starting leftfielder. Also given a good chance of making the club are two more rookies, Shortstop U. L. Washington, who would serve as a reserve infielder, and Pitcher Rich Gale.

This kind of competition pleases General Manager Burke because he prefers to promote players from inside the organization rather than to load up in the reentry draft, the route division rivals Texas and California have taken. "It looks like some of our veterans are going to have to bite the dust," says Burke.

Hurdle came to the attention of the Royals through a stroke of geographic good fortune. He grew up in Merritt Island, Fla., near the Cocoa home of the Royals' minor league pitching instructor, Bill Fischer. Fischer watched Hurdle play high school ball in the spring and pitched batting practice to him during the winter. "By the time Clint was 17," Fischer says, "he was hitting the ball over the fence and into the drainage ditch. I quit working out with him more out of fear than anything else. I was afraid I might get killed."

Fischer showed less compassion for the pitchers in the American League, and in the spring of 1975 he recommended that Kansas City draft Hurdle. The Royals wanted another opinion, so they brought Hurdle to their minor league complex in Sarasota to take batting practice under Lau's watchful eye. "From the time he took his first swing there was no doubt in my mind," Lau says. Adds Fischer, "It was the greatest exhibition you ever saw."

The Royals made Hurdle the ninth pick of the first round and signed him for a reported $50,000 bonus. The big loser was the University of Miami, which had signed Hurdle, an All-State quarterback, to a grant-in-aid.

Hurdle rapidly rose through the Royals' minor league system. At Sarasota, he made the Gulf Coast League all-star team. He almost met his waterloo at Waterloo, Iowa, where he hit only .180 in the first half of the season, but he surged to .235 and was named prospect of the year in the Class A Midwest League. Because of a stipulation in his contract, Hurdle was invited to Kansas City's training camp last spring even though the club had already ticketed him for Double-A at Jacksonville. "Wait a minute," Hurdle said. "How about seeing what I do here first?"

What Hurdle did was hit .300 against big league pitching, and he landed in Omaha, the Royals' affiliate in the Triple-A American Association. After hitting .328 with 16 homers and 66 RBIs, he was named the league's Rookie of the Year and Most Valuable Player. That earned Hurdle a brief trial with Kansas City at the end of the season, and all he did was bat .308 with two home runs and seven RBIs in nine games.

When he made his debut on Sept. 18, he was barely past his 20th birthday, making him the youngest Royal ever in the club's nine-year history. He celebrated the occasion by hitting a 450-foot home run and signing autographs for an hour and a half after the game. Playing winter ball in Venezuela, he hit .305 and was either first or second in homers, RBIs and runs scored.

But Hurdle does have some deficiencies. For one, he is not very fast. For another, he is a notoriously slow starter at bat. In Omaha last year he had only eight hits in his first 55 at bats. Despite his youth and impetuosity, he does get good marks for maturity and discipline on the field. John Sullivan, Hurdle's manager at both Waterloo and Omaha, says, "He may have been only 19 last year, but it seemed like he was 19 going on 29."

"I'm not getting any younger," Hurdle says. "My career has been like a book and this is the climax. I'm just going out and deal. I've got my chance and if I don't make it I won't have anybody to blame but myself."

Among those who have no doubts that Hurdle can make it is Brett, who predicts a .300 average for Hurdle in his rookie season. Only four years ago Brett was himself a 20-year-old trying to break in, and he knows just what Hurdle will have to go through. "Clint is a lot like me," he says. "I guess that's one of the reasons we've become close. In 1974 I was the All-American boy trying to make it in the big leagues, and now it's Clint. I can remember the front office asking me not to chew tobacco or go into bars. I was their golden boy. Now the golden boy is Clint, and they'll probably want to protect him, too."

In order to keep an eye on Hurdle, Manager Herzog has threatened to take him on every Royal road trip this spring. Fort Myers is 100 miles from the Royals' closes big league rival, and four-hour bus rides every other day or so are one of the club's rites of spring. But the Royals will probably have no more success putting a bridle on Hurdle than they had with Brett.

"You've got to get it while you can," Hurdle said last week while cruising through Fort Myers in his new Dodge van, a homey vehicle equipped with a refrigerator, sink, CB radio, stereo tape deck, fold-out bed and spittoon. Hurdle keeps a harmonica within easy reach on the padded dashboard, and the refrigerator behind him is never empty.

"When I've had a few drinks," he says, "I want to get Rubin [Hurricane] Carter out of jail. When I came up to Kansas City last season I thought life in the majors would be great, but it was 10 times better than I expected."

In anticipation of this season's pleasures, Hurdle asked the club for a single hotel room on the road, a perk normally reserved for veterans. His request was denied, but he says, "I'll get it next year." Meanwhile, he has purchased two dozen Kansas City Royals T shirts that say ALL THE WAY IN '78.

If Hurdle does not go all the way himself, he will be "really teed off." "I'm a little cocky," he says. "I have a flair for the extraordinary. I know I have a lot to learn but I'd rather do it here."

As far as Herzog is concerned, he will. "Hurdle has to prove to me he can't play," the manager said last week. Proving he can't play may be about the only thing Hurdle cannot do.