Bobby V's Super Terrific Happy Hour

The Most Hated Man in Baseball is now adored.

His name graces a street, a brand of bubble gum and a lager. He smiles back from ATM screens, lectures to college classes, draws throngs when he appears in public. Six thousand miles from New York City, Bobby Valentine is a star.

"You gotta check this out," he says as he cues a music video on the desktop computer in his apartment in Chiba, an eastern suburb of Tokyo. From the speakers comes a synth-pop beat, and on the screen members of the Japanese band DEEN bounce into view. They are greeted at a fake press conference by Valentine, who "signs" the musicians to the Chiba Lotte Marines, the team he manages. The camera rises to focus on a disco ball, and when it pans back down, the room has been transformed into a dance club. There, amid swirling lights and pulsating music, is the 56-year-old Valentine, now in a tight blue shirt unzipped to display a healthy acreage of chest. He does the cha-cha with a beautiful young woman, twirling across the floor and shaking his hips to the rhythm. The video ends with Valentine winking at the camera.

"It went to Number 5 on the charts in its first week," says Valentine, his dark eyes wide with delight. "The kids here love it."

There is no irony in the video -- the song is called Shining Ball, and the chorus translates as "this [baseball] diamond is just so beautiful" -- or, for that matter, in Valentine. The former Mets and Texas Rangers manager has embraced Japan, and it has embraced him back, if at times awkwardly. Here baseball is about teamwork (the phrase for it is wa), but the Marines are not about wa. The Marines are about Bobby. He is a combination of manager, mascot and star player. There is a small shrine to him at the entrance to the Chiba stadium, and the concourse walkways are lined with 10-foot-high Bobby V murals bearing his aphorisms, informing fans, for instance, that The team is a family. A happy family makes the team stronger. He is a visiting professor at four Japanese universities, his number 2 jersey is a hot seller, and of course there is BoBeer, the Sapporo brand that bears his likeness. Not that long ago, readers of Weekly SPA!, a magazine that caters to young businessmen, voted him the person in Japan they would most want as their boss. There is a phrase for the effect Valentine has had on the game, and for his style of managing: Bobby Magic. Or, as it's usually pronounced here, BubbyMagic.

The adulation stems from the 2005 season, when Valentine inherited a band of rookies and veteran underachievers and led the Marines to their first Japan Series title in 31 years. Two weeks later they won the Asia Series, besting the Chinese national team and league champions from South Korea and Taiwan. Four months after that, eight of Valentine's players helped Japan win the World Baseball Classic. Last season the Marines faltered, finishing 65-70, but they still set attendance records, in part because of Valentine's Veeckian flair for promotion.

Managing the Marines is, in many ways, the perfect job for Valentine. He wields near-complete control over the team -- acting as both coach and de facto general manager -- in a city that idolizes him. At roughly $3.5 million a year, he makes more money than any major league manager in the U.S. except Joe Torre. The U.S. press dogged Valentine during his tenures in Texas and New York, but the Japanese media is docile to a fault. A year and a half ago the Los Angeles Dodgers and the Tampa Bay Devil Rays called to try to lure Valentine back to manage in the U.S., but he didn't seriously pursue either lead. "This is an opportunity of a lifetime," he said of running the Marines, "and I'm living it."

Still, something eats at the man. Spend time with Valentine and it becomes clear that he has everything except what he truly craves. And that is why he agonized over his team's slump last season, why he bristled when some rival club executives in Japan suggested that his 2005 success was a fluke, why he is so eager to show off the spoils of his success. It is why he beats the drum for Japanese baseball, hoping he can make a noise loud enough to carry over the stadium, past Mount Fuji and across the Pacific to a country that remembers a different Bobby Valentine, one who never won the World Series, who was fired from two jobs and deemed by one newspaper as the game's most despised figure.

So Valentine campaigns to change not just a culture and a game but, in the end, a reputation: his own.

Valentine was in Japan once before. In 1995, after the Rangers fired him, he came to Chiba and managed the Marines for one season. It did not go well. He fought with management and feuded with the players -- though the fans loved him. Despite leading the Marines to a 69-58-3 record, their first winning season in 13 years, he was fired. Now when he speaks to Japanese audiences, something he is frequently invited to do, he starts with a self-deprecating crack. "I am the only guy in the history of the world to manage in the American League in the MLB and the National League in the MLB and the JPL of the Japan professional baseball league," he'll say. After pausing for applause, he'll add, "I'm also the only one to be fired in the American League ... and the National League ... and the JPL of the Japan professional baseball league."

In the case of the JPL, fired and rehired. Eight years after his first stint with Chiba, Valentine returned as a conquering hero. He'd been to the World Series with the Mets in 2000. He'd also become notorious: Valentine was the man who wore the fake glasses in the dugout after getting kicked out of a game, who fought with Mets management and New York beat writers, who had the balls to say what he thought even when the ballsiest thing might have been to keep his mouth shut.

To the Japanese, whose love of baseball rivals America's, Valentine's return was the ultimate affirmation. A World Series manager choosing to come back to Japan validated the Japanese game. Most of the previous gaijin in the JPL had been either washouts in the States, such as Tuffy Rhodes, or aging power hitters in search of one last big payday, such as Bob Horner and Kevin Mitchell. That Valentine had taken the time to learn Japanese, which he speaks proficiently, and that he'd had success during his first go-round in Chiba only made him more lovable. "He understands the heart, and always gives respect," says Yukiatsu Akizawa, the president of AM/PM markets, a sort of Japanese 7-Eleven, and a friend and business associate of Valentine's. "Bubby is magic."

Valentine's appreciation of Japanese baseball history helped as well. The game has been played here since 1872, and its icons are beloved, from 1950s slugger Makoto Kozuru to alltime home run king Sadaharu Oh to present-day stars such as Ichiro and Daisuke Matsuzaka. Tokyo and its suburbs support five pro teams, and fans travel to away games in packs, bringing drums and horns and executing coordinated cheers (a different one for each player). During a Marines game the rightfield stands come alive with tatenori: 2,000-odd souls pogo up and down like a field of Whack-a-Moles. The fans cheer for each player and his contribution; one cheer goes Otsukaresamadesu. It translates roughly as "Thank you for your fatigue."

Effort, tradition and teamwork are prized in Japanese ball, and practice is a ritual in itself, to be perfected. "To the Japanese players, getting there early, taking your fielding, your bunting practice, all of this counts," says Frank Ramppen, one of Valentine's bench coaches. "You take pride in each element. If you work hard on all those things but the team loses, you still had a successful day."

Valentine has succeeded in simultaneously honoring and doing away with these traditions, and that's part of what made him a revolutionary of sorts -- the beloved king of the gaijin.

It is an afternoon in August 2006, late in the baseball season, and Valentine is driving through Chiba in his custom-made BMW, gunning the gas and listening to a Gwen Stefani song on the radio. This morning he returned from a road trip by train, using the three-hour ride to study Japanese from the yellow folder he keeps in his travel bag. Valentine likes the language but chafes at its formality, empathizing with Bill Murray's character in the film Lost in Translation. "When he's filming the ad and it takes forever to say the shortest thing -- I've been there," Valentine says. "It's because you can't just say 'it's f------ hot' here. You have to say, 'The temperature is warmer currently than in a relative fashion to the temperature yesterday,' because you don't want to offend anyone."

At Tokyo Station he was briefly besieged by fans with camera phones. ("Got to keep moving, it's the only way to avoid the mobs," Valentine explained as he zigzagged through the crowd.) From there the commuter line took him east toward Chiba -- past Tokyo Disneyland, with its eerily perfect replica of the U.S. version, and through acres of industrial warehouses. Gray predominated: It was the color of the roads, the sky, the water, the buildings, the suits of the businessmen on the train. Valentine, in his pink polo shirt, was the exception.

Now, as he drives home, he points out landmarks: the stadium, the park and Valentine Way, which was lined by 240,000 people for the Marines' victory parade in the fall of 2005. The city planned the celebration for days, with great precision. Fans cut the confetti into perfect little slices to make it easier for the street sweepers to pick up. Within hours of the parade the asphalt was immaculate.

That season was, Valentine says, "one of those times when everything goes right." The Marines came out hot and finished the season with the most runs scored and the fewest allowed. Valentine's approach was novel, at least for Japanese baseball. He used his bullpen liberally, changing pitchers based on matchups. He made late-game defensive replacements. He changed lineups 120 times during the season. And he did something heretical: He didn't bunt. In Japan the sacrifice is sacred, a symbol of the team's predominance over the individual. Even power hitters bunt runners over. Valentine bunted only for a hit. In his first stint in Chiba his players had at times disobeyed him, bunting against his wishes and once practicing without him when he had given them a day off. So in 2005 he'd brought help from the States in the form of Ramppen, a longtime friend and former scout, and hitting coach Tom Robson. Both were guys from back in the day, guys he could trust, guys who could help him break the Japanese players of their habits, however well-intentioned those might be.

Valentine's strategy won games, but it was his enthusiasm that won the pennant. As Horner, the ex-National Leaguer turned Japanese league slugger, recounted in Robert Whiting's You Gotta Have Wa, the Japanese game is really "work ball," whereas in the U.S. people play ball. Valentine stressed that the game should be play and that it should be passionate. "I'd stand next to Bobby during his postgame speech, on the steps of the dugout, and I'd look at the players' faces while he was talking," says Ramppen. "And I told Bobby, 'They don't give a f---.' Bobby would get mad at me, but it was true, they didn't. I could tell. And once we started to win, you could tell that they started to care."

The younger players in particular responded to Valentine. "In the past some Japanese coaches told me, 'It's supposed to be fun, have fun,' but coming from them, I didn't know what that was supposed to mean," says Toshiaki Imae, the Marines' 23-year-old star third baseman. "Bobby's different, because if he asks, 'Do you have fun?' it means he really wants you to have a fun time on the field. From the Japanese coach and from Bobby Valentine, the same words but a different meaning."

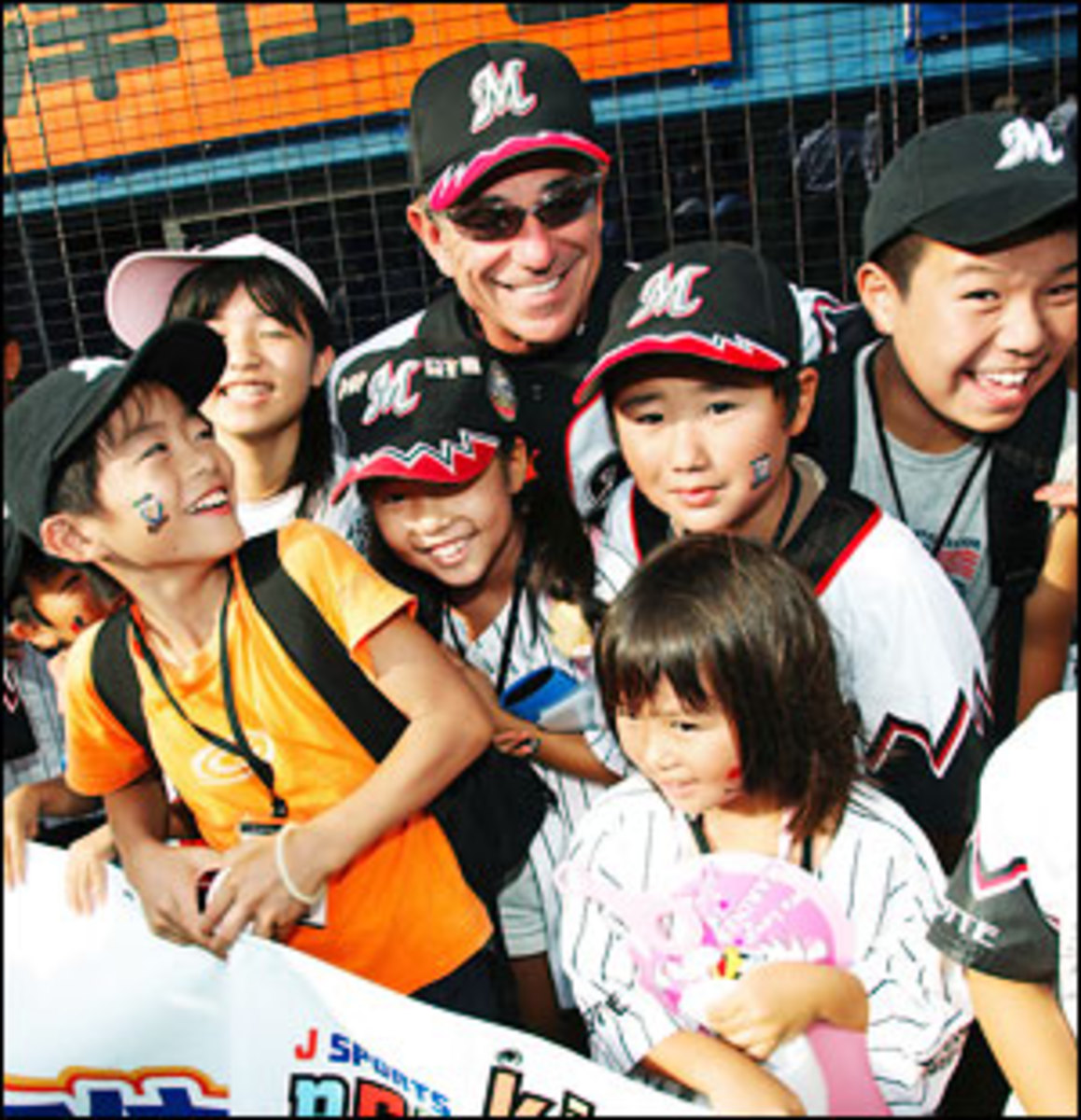

Valentine thought the fans should have fun too. One of his first moves was to cut a slot in the 14-foot-high fence down the rightfield line. Before every game he walked down there and signed autographs -- something Japanese players and managers never did -- and he ordered his players to do the same. The opening came to be known as Bobby's Window.

Autographs were just the beginning of the marketing makeover. Valentine had the team add a section of seats down the first and third base lines so fans could be closer to the action. He ordered luxury boxes upgraded, brought in more (and better) food vendors and pushed to build a team "museum" in which a fan could have his photo taken with a life-sized Bobby cutout, peruse replica lockers or pose for a picture as if he were being thrown in the air, as Valentine was after the Marines won the championship. Before Saturday-night home games Valentine, who was a ballroom dancing champion as a teenager, teaches the cha-cha to Marines fans as a way to attract women to the park. (It's worked; more women and children buy tickets to see the Marines than to see any other Japanese baseball team.) The Marines also started a loyalty club, similar to a frequent-flier system, that allows fans to trade in points for tickets and merchandise. It now has more than 70,000 members and has brought in 270 million yen (roughly $2.3 million) in revenue.

Valentine and Larry Rocca, a former Mets beat writer at the Newark Star-Ledger whom the manager hired to head the Marines' promotions-and-marketing department, even found a way to inspire fans to camp out for admission to a regular-season game: On 360-Degree Beer Stadium night, from the moment the gates opened at 5 p.m. until the end of the game, all beer was half price. Along the concourse each beer maker had its own gantlet of servers, all young, attractive and perky, with taps at the ready. Kirin's girls wore neon green and yellow, Suntory's wore red, and Sapporo's 13 women were dressed in black, with shirts that read i § beer. Roaming the stands were even more servers, each outfitted with a beer backpack -- essentially a pony keg in a sling -- and a tap. The Marines sold 50,000 beers, or an average of more than two per adult in the crowd. It was enough to make the dingy concrete bowl of a stadium seem festive.

Wherever a product tie-in is possible, the Marines make it. You can buy a Bobby Valentine box lunch (tomato, beef, broccoli, rice) or chew Marines bubble gum (embossed with a caricature of Valentine's smiling face). During pitching changes, a Volvo logo appears on the scoreboard and a Volvo with one door cut out drives the pitcher from the bullpen to the mound. Valentine wanted a mascot, so the tall, wide-eyed Rocca pulled a clown wig over his thinning blond hair and became M-Crash. Gregarious, bright and profane, Rocca was perfect for the job, and by the end of the '05 season M-Crash was a sensation (and something of a sex symbol).

Come midseason the Marines were selling out games, and by the end attendance had tripled, to 1.3 million. After winning the title, the Chiba players celebrated by spraying 3,100 bottles of beer (to represent their 31 years of futility) and 260 bottles of champagne (to represent the fans, the "26th man") at a luxury hotel downtown exactly two hours after the game. As is Japanese custom, the players and coaches wore protective eyewear, literally donning beer goggles. "There were a lot of people who were crying," remembers Benny Agbayani, the Marines leftfielder and a Valentine favorite from their days together with the Mets. "The team had always been in fifth, sixth place. These guys didn't know what it felt like to win."

Neither did Valentine. After 36 years in the game, he had finally won a championship, and was being celebrated for it. He became the first foreigner to win the Shoriki Award, presented annually to the person who makes the greatest contribution to Japanese baseball. Parades were held, commemorative magazines printed.

"It was the best experience I've had in the game," says Valentine. Surely he would be recognized for his genius back home.

Few in Major League Baseball deny that Bobby Valentine can manage. He is acknowledged to be one of the best minds in the game, and few managers work harder to gain an edge on an opponent. (Valentine was famous for studying video, and the cameras he had installed at Shea Stadium led to accusations that he stole signs.) "What was unique about [Valentine] was his game approach," says San Francisco Giants' G.M. Brian Sabean. "He was a top-step guy who watched every pitch. You didn't see him overchecking lineup cards and rifling through matchup stats. He had a general idea what he was going to do on a given day and what personnel he was going to use. But more important, he watched the game. You have to have a feel for that. I don't think he gets quite the credit he deserves."

Oakland A's designated hitter Mike Piazza, a former Valentine favorite with the Mets, also praises his old skipper, but it comes with a caveat. "He's definitely one of the smartest managers I've known -- but he can also be unpredictable."

The issue in the States, in other words, was never Valentine's skill as a manager. The issue was his personality. While some were drawn to him by his charm and confidence, others saw him as condescending, still others as arrogant. This is probably why, after winning 581 games with the Rangers, he had to go back to the minors and then Japan before getting another major league job. It's probably also why, after being fired by the Mets, he ended up in broadcasting, then back in Japan.

Still, he cherishes all his baseball memories, which is evident when you visit his apartment. Valentine lives about two miles from the Chiba stadium, so he can bike to work. His top-floor apartment, with a balcony from which, on a clear day, you can see Mount Fuji, has three bedrooms, two guest rooms and the feel of an upscale bachelor pad. There are leather couches and cases of BoBeer. Perched on almost every horizontal surface are mementos: a black bat with the names of all the Marines players, photos of Valentine with the last three U.S. presidents (to bobby valentine, best wishes, reads the note from George W. Bush, his onetime employer with the Rangers), photos of Valentine doffing his cap, photos of him with the team, photos of him with heads of state, photos of him with his family. There are, it turns out, few photos in the apartment that don't have Valentine in them.

What is most striking about the pictures from New York is Valentine's appearance: His hair is gray and thinning, brushed back from a widow's peak, and he looks tired. Today his hair is dark brown, fuller and brushed forward. He smiles often and works out for an hour and 40 minutes a day. (He teaches a dance class at Gold's Gym in exchange for a membership.) He looks five, even 10 years younger.

His life is dominated by the game. He says he doesn't get homesick but rather "friend-sick," so he flies his buddies out to Japan. He sees his wife, Mary, every five weeks for a homestand. "Mary's great about it," he says. "She understands I need something to do. I go on vacation for two days, I'm sitting on a beach and I'm supposed to relax. Relax? I need something to do. People say, 'Play golf.' Maybe when I'm 63, but not now. I'm not just taking money here, this isn't cake. I work 11 a.m. to 11 p.m. But I work out more, I feel better, I'm not stressed. It's about passion."

Most nights Valentine goes out to dinner and talks baseball. Those who know him say he's mellowed. "With the Mets we had a lot of meetings," says Agbayani, who played for Valentine on the 2000 World Series team. "[Last] year we had a few meetings, but he's been very calm. He's so supportive. In the Mets days he'd be yelling."

Asked about this, Valentine harrumphs, "Well, there are a lot more reasons to be calm here. I don't have to deal with a lot of the s--- I had to deal with over there."

This is partly by design. In his second stint with the Marines, Valentine was granted nearly absolute power. Uniforms? He designed them. Draftees and new acquisitions? He picked them. New team executives? He recruited them. As his right-hand man he brought in Shun Kakazu, a 26-year-old with a Harvard degree. (He wrote his thesis on undervalued players in Japan.) Kakazu functions as an assistant G.M., going over scouting reports with Valentine and analyzing stats.

To legitimize his success, Valentine realizes he must also legitimize Japanese baseball, which Americans have long thought of as "Four A" ball. This becomes harder with every defection to the States by a Japanese star and every successful transition to the Japanese system by a marginal major leaguer. So whenever possible, Valentine proselytizes on behalf of Japan's league. "I made a statement last year that my team that won the Japanese championship could have played against the [2005 World Series champion] White Sox," he says, "and some baseball people said, 'Oh, hell, the talent level doesn't match up. Bobby's just talking.' My statement was made in the belief that we were playing at the highest level of any team I'd ever seen play. I knew that without a doubt. We didn't have as much talent -- I never said we did, and I never will -- but with our heart and the way we played, the way we built as a team and built individually during that season, we could have beaten any team in the world."

Whether Valentine truly believes this is unclear. But the statement certainly attracted attention -- White Sox manager Ozzie Guillen laughed at it -- and attracting attention is something at which Valentine is an expert. "One of the things people like and dislike most about me," he says, "is that I open my mouth, I say stuff." His whole body comes alive when he launches into an opinion or a story, reveling in triumphs past, foes vanquished. Pull out a tape recorder and he amps the performance up a notch, moving into broadcaster mode. He slows down, emphasizes words, speaks in paragraphs, uses exaggerated hand gestures. When asked over lunch one day if there are common misconceptions about Japanese baseball, his answer lasts more than five minutes. Only the arrival of the food keeps him from going on longer.

Valentine has always been eager to talk, but he is even more eager when a U.S. journalist comes to Japan. After that initial interest from the Devil Rays and the Dodgers at the end of 2005, he's had little contact with Stateside teams. (Although Valentine is under contract with the Marines through the '09 season, he says, "If a baseball conversation leads to a baseball situation that I feel is a great fit, one of those opportunities of a lifetime, I'd talk.") Despite his success, few in the States look to him for advice, something that perplexes him. "You know what I'm really surprised at is that when teams are interested in signing a guy [from Japan] they don't call me," Valentine says. "Information is power, and I got a lot of information here, so I can make other people more powerful here if they want it."

Does he have any idea why teams wouldn't call him? "I don't know," he answers. "I really don't."

There is a Japanese phrase that Valentine likes to quote: Chisai kuni desu kara. It means "because it's a small country." "People ask why there are no garbage cans," he says, "and they answer, 'because there's no litter.' Ask why there is no litter and they say, 'because it's a small country.'"

Japan is not, of course, a small country.

It has 127 million people. But its customs can be intractable. There is a Japanese axiom, "The protruding nail gets beaten down." Valentine refuses to be hammered down. Rather he is the claw grip, trying to yank free whatever he can. He wants to exact big change -- change his franchise's operations, the way the league promotes itself, the way its minor league functions -- and, as he did in the States, he has little regard for those who come between him and progress.

It is a fall evening near the end of last season, and Valentine has left his apartment to go out to dinner with his minor league manager, Hide Koga, and a Mets foreign scout, Isao O'Jimi, who worked with Valentine in New York and now serves as an informal adviser and drinking buddy. Koga, 66, has a white flattop and a mustache that perches like a thin white caterpillar on his upper lip; he played with Sadaharu Oh and coached in the U.S. minor leagues. Valentine is involved in a struggle with Koga over how to teach the game. He wants Koga to do it the American way -- the Bobby way -- but Koga can't help himself: He still believes in bunting runners over, in trying for slap hits.

In 2005 that wasn't a problem, but in '06, as the Marines struggle -- they are a .500 team at the time of this dinner -- men like Koga can't help but wonder whether the Japanese way isn't better after all. Even the phrase Bobby Magic belies a popular skepticism. "That magic stuff, what s--- is that?" says Ramppen. "They don't want to credit the gaijin here."

Valentine has set up this dinner in part to talk about the upcoming draft with O'Jimi and in part to have a sit-down with Koga. The food is extravagant -- lobster, abalone, goose liver, filet mignon -- washed down with pints of Kirin and glasses of sochu, a potato liquor similar to vodka that, the Japanese claim dubiously, does not cause hangovers. It doesn't take long for Valentine to get into it with Koga.

"We've had this conversation a thousand times," Valentine says. "The Japanese f------ way. You've got our hitters not swinging through the ball. All your hitters suck."

"But I was Don Baylor's interpreter," Koga replies, "and he said -- "

Valentine cuts him off. "I don't care," he says. "That was 20 years ago, Hide. Besides, Don Baylor's an idiot." Valentine is just getting warmed up. "A lot of things can happen if you teach them to bunt for a hit, like I keep telling you. The last three years it was a good play, but this year, well...."

O'Jimi joins in: "Bubby, I hear your fourth hitter, the catcher, bunts by himself."

Valentine nods. "Nine times ... because he wants to show his teammates he's unselfish."

Koga wants to blame the Marines' hitting woes on Robson, the American hitting coach, but Valentine won't let him. "He's a lazy gaijin, O.K., he is," Valentine says of his friend, "but it doesn't mean that what he did last year was wrong." He pauses. "This year no one wants to make a mistake. What the f--- is that?"

Koga has no answer. He frowns. Valentine frowns back. "Hey, we could go back to being mediocre, I don't care," the manager says. "It's only my life's work."

As Valentine chastises, he also tries to teach. He obviously likes Koga; he is just frustrated by him. So Valentine hammers home the Bobby way. Koga asks about a Marines prospect who's afraid to steal because he's not 100% sure he'll be successful. "You must allow him to get picked off first base without saying he's stupid or a rookie, so he knows how far to go without getting picked off -- so he has freedom," says Valentine. "It's like skiing. If you always ski the easy run, you never learn. You must fall down to learn."

At one point Valentine offers the team president job -- currently held by Ryuzo Setoyama -- to Koga. "Hide, why don't you be my G.M.," Valentine says, pointing his Kirin at Koga. "Think about it. I know you like to teach, I know they need you. But the food's a lot better up here than in the minor leagues. Go on the road with me, have nice dinners."

Koga is reluctant -- he likes working with players -- but Valentine says he'll come back to him on it. More food comes, followed by more Kirin, and Valentine can't help himself. "I'm not one to brag often ... O.K., all the time," he says. He has to preach his gospel. He sits, legs spread, an alpha male in a position of power, and holds forth: on old teams, old grudges and his players.

About his starting shortstop, Tsuyoshi Nishioka: "He sucks this year. He's s---."

On Mitchell, the former Giant who played briefly in Japan: "A great guy but the worst gaijin ever to play here."

On why Kenji Johima, the catcher for Mike Hargrove's Seattle Mariners, is platooning behind the plate: "Because his manager's an idiot."

Three months late the season is over and the U.S. is crazy about Japanese baseball, but not about Valentine. Matsuzaka, the star pitcher for the Seibu Lions, dominates the news. Valentine? He is mentioned as an outside candidate for the Giants and the Washington Nationals jobs. But he is interviewed by neither team.

Valentine has come back to New York City. The Japanese Chamber of Commerce is honoring him with its Eagle on the World Award, given annually to prominent figures who further Japanese-American relations. The other honorees are former Deputy Secretary of State Dick Armitage and Japanese astronaut Soichi Noguchi. The awards presentation is at the New York Hilton in midtown Manhattan. It is a swank affair: black tie, filet mignon, stylish Japanese women on the arms of powerful executives from companies such as Sony, Panasonic and Sumitomo. A popular Japanese singer, Yosunake, opens the evening with a couple of rousing numbers in his native tongue, then finishes by singing New York, New York decked out in a glittering sequined floor-length coat.

Valentine is introduced. "In Japan he's taken the status of rock star," the host says. "He not only raised the status of baseball to rival that of the United States, but he's a master of human chemistry." Valentine nods at the compliment, takes the stage, makes a couple jokes in Japanese and opens with the anecdote about being the only person to manage in the AL, NL and Japanese pro ball and also be fired in all three leagues. He thanks the crowd, then addresses the subject of Matsuzaka. Only 24 hours earlier the Red Sox successfully bid $51.1 million for the right to negotiate a big league contract with him.

"Here, the day after the great 26-year-old pitcher Matsuzaka, from the Seibu Lions, took that bridge that I'm trying to build -- he took that bridge over to play in the United States -- I have to say that I have very mixed feelings," Valentine says. "One is the joy, for him, his family and my team, because he won't pitch against us again. But also one of sadness and disappointment in the professional league of Japanese baseball for allowing him, a great national treasure, to in fact leave their league. I think that this audience here, which is building many bridges of commerce and industry between two of the greatest economic countries in the world, must be reminded at this time that Japan has a sport that is their national sport. There are 150 million people there and the true national sport is baseball, the only industrialized country in the world that the national sport is baseball."

Valentine pauses to let his words sink in before he resumes. "And that in itself is a great resource. And it should be looked at as something that should be treasured and kept and cherished and cultivated and nourished, just as your companies are developing and growing. And the same type of synergy that's in this room should be involved in making Japanese baseball a world power. Not only on the field, because the players can play, but also in the front office and the ownership level so that the players can be paid what they should be paid and stay in Japan to keep that league as strong as it can possibly be, so that my dream of a true World Series will in fact come true in the very near future."

The crowd cheers politely, but the real audience for Valentine's comments, the world baseball community, does not hear them. Despite the event's location in New York City, I am the only member of the U.S. media present.

So Valentine slips off into the night, neither harassed nor feted in his home country. All of the major league managerial openings have been filled. As a result Valentine will spend the 2007 season, which began on March 24, as the Marines' manager, an increasingly invisible figure to baseball fans in America. Perhaps it is the price he must pay for his nearly perfect life in Japan. Since Japanese baseball is not considered world-class, his accomplishments there do not carry much weight at home, and since the best Japanese players keep leaving for the States, he cannot make Japanese baseball world-class, no matter how many bridges he builds or box lunches he sells.

Thus Bobby Valentine remains stranded somewhere in the middle of his own bridge, a man caught between two worlds, a hero in the wrong country.