Game changers

But those plays are what make today's NFL worth watching. To see one of the little people backpedal toward his own end zone, pluck a ball out of the sky, run figure eights around an onrush of giants, and leave them hyperventilating in his wake, is to witness the most exciting spectacle in football. It happens about twice a weekend.

The NFL's main attraction used to be its quarterbacks and tailbacks, the guys who always had the ball in their hands. Now, the main attraction is the return men, guys who rarely have the ball in their hands. With offenses failing to solve complex defenses, the little people often make the difference. They do not need a perfect pass or a carefully cultivated game plan to score a touchdown. They just need to get the ball and run.

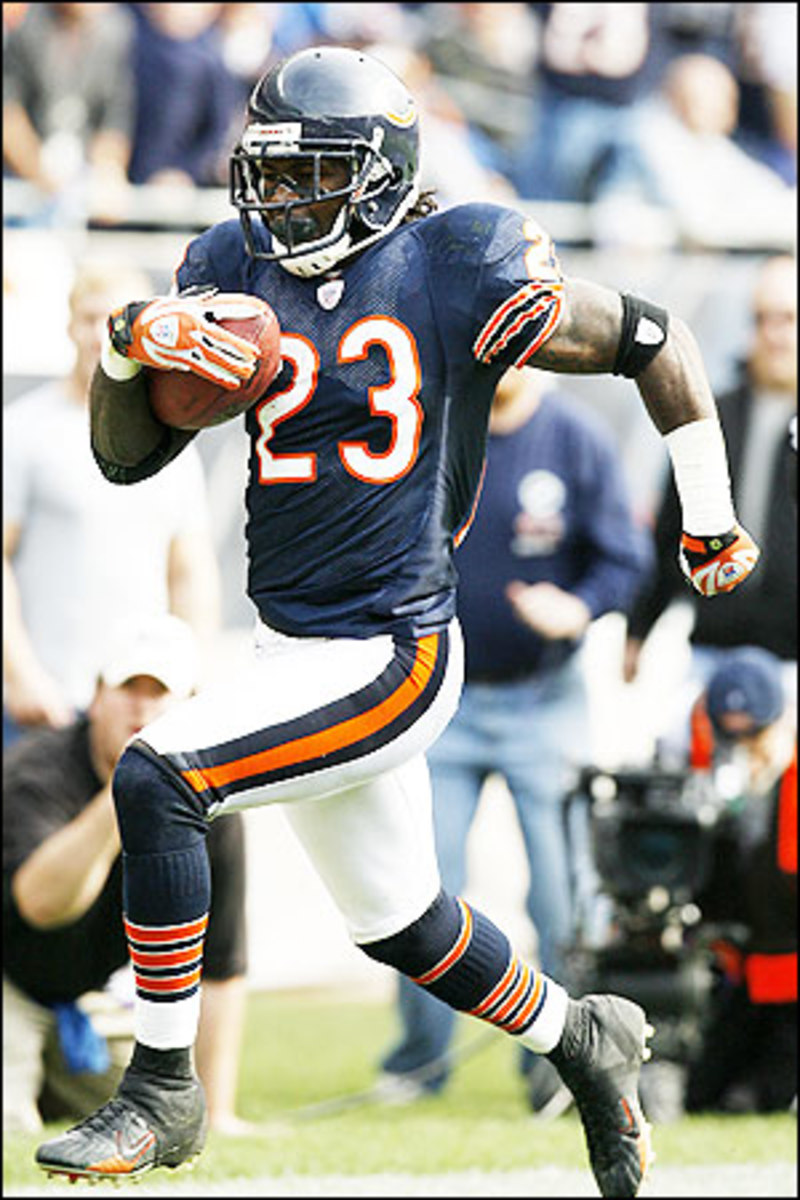

While teams have had difficulty identifying star quarterbacks in recent years, they have had no such issue with return men. Players once relegated to the fringes of the depth chart have become part of the mainstream: Chicago's DevinHester, Cleveland's Josh Cribbs, Buffalo's Roscoe Parrish, the Jets' LeonWashington -- the list is 100 yards long.

Playmaker, a term overused in sports and especially in football, can refer to almost anyone outside the offensive line. But increasingly, playmaker is synonymous with return man. These little people are the ones most likely to generate a game-changing, momentum-swinging, did-you-see-that and can-you-believe-it moment.

Most teams have such a player on the roster. Those who do not are searching feverishly for one. Last year, the Miami Dolphins drafted Ted Ginn Jr. with the ninth overall pick, partly because he could catch passes, but mainly because he could return kicks.

We have entered the golden age of the kick return. This season has already seen 22 kickoff returns for touchdowns, a new record. Six of those have gone for 100 yards or more. In contrast, over the past two seasons, there were only two for 100 yards or more.

Touchdown returns have become so prevalent, even Tampa Bay got one. Micheal Spurlock went 90 yards against Atlanta on Sunday, the first time the Buccaneers returned a kickoff for a touchdown since they entered the league in 1976, a span of 1,864 kickoffs.

"It seems like a lot of teams are starting to pay more attention to their special teams," Hester said. "They are trying to take it the distance."

Hester is clearly the godfather of the modern return game. Last season, he took back three punts for touchdowns and three kickoffs, including one in the Super Bowl. NFL teams, known for their copycat ways, all wanted their own version of Hester. Not only did the Dolphins draft Ginn in the first round, the Ravens took Figurs in the third.

"They said how important the return game is," Figurs said. "It's something they need. You thank all the guys who came before you, like Devin Hester."

Figurs is typical of an elite return man. He is young (24), fast (runs a 40-yard dash in 4.3 seconds) and comes from Florida (Fort Pierce). Growing up, he played a game with his friends called "throw-up tackle," in which he would throw up the ball, catch it, and run until one of his friends tackled him. It was early practice for his role on special teams.

Like every return man, Figurs has greater ambitions. His natural position is wide receiver and he is listed as such on the Ravens' roster. But he has yet to make a catch this season. Figurs is suffering from a common problem: Although return men are among the most electric players in the league, teams have not found a way to maximize their skills.

"It takes time to work into that dual role," Figurs said. "It's just getting experience. Football is pretty specialized now."

As NFL teams grow more desperate on offense, they search for ways to involve their playmakers. Usually, this results in reverses, short passes and various trick plays. Sometimes, the return men are even positioned in the end zone during opponents' field-goal attempts.

Last season, Hester returned a missed field goal 108 yards against the Giants. This season, San Diego's Antonio Cromartie returned a missed field goal 109 yards against the Vikings. But even that record-setting dash could not make Cromartie the Chargers' regular return man. The position is occupied by Sproles, who ran down the Indianapolis Colts this season with two returns for touchdowns in the same Sunday night game.

Cromartie is a unique brand of playmaker. He is not the Chargers' return man and was not in their starting lineup until recently. Listed primarily as a backup cornerback this season, he still leads the NFL with nine interceptions. "My goal is to get in there and play in the nickel package and do whatever I can," Cromartie said modestly.

Cromartie has asked the Chargers about playing some offense, like Hester does for the Bears. But Hester has not been nearly as successful on offense as he is on special teams. Return men are a specific breed. They need space to operate and time to see the whole field. Putting them one-on-one with a cornerback often limits their ability.

"I honestly think Devin can be a good receiver," Parrish said. "I know I'm a good receiver. I don't look at it like returns are all we do. I played receiver and quarterback growing up. I've never been just a returner. I guess it's something we just get labeled as."

Parrish is one of Hester's closest friends in the league. They both went to the University of Miami and text message each other after every game. If Hester or Parrish returns a kick for a touchdown, the text message will read: "I got mine today."

The spike in special-teams touchdowns this year is due mainly to dynamic return men, but also to lackluster coverage units. Since free agency, it has been harder for teams to maintain continuity on special teams. And because of the salary cap, clubs are more likely to use rookies for coverage units than highly paid veterans.

To hide their deficient coverage, kickers usually aim for touchbacks, with low and deep line drives. But elite return men are often encouraged to run balls out of the end zone. There is obviously a chance that they will be tripped up inside their own 20-yard-line. But they will gladly accept that risk for the opportunity to go the distance.

If teams cannot score with 50-yard passes or prolonged touchdown drives, they need to find another way. They have to trust their little people.