SI Flashback: The Fast Lane

She lay on the living room floor of her family's Los Angeles house in 1981, watching the royal wedding of Charles and Diana on television. Marion Jones was five years old, a little girl creating her own vision from the pictures on the screen. "They have a red carpet to walk on, because they're special people," she chirped to her mother and her brother. "When will they roll out a red carpet for me?"

They're in the process even now. The rug is thick and plush, unfurling toward the millennium. In the autumn of 2000, Jones could--no, plans to--win five gold medals at the Sydney Olympics, having by then, at the doddering age of 25, run faster and jumped farther than any other woman in history. She might then (or later, but eventually) switch from track and field to basketball and resume playing the sport in which she scored 1,716 points in three years at North Carolina. "As an elite two-sport athlete, she would be in a class by herself at that point," says Gary Cavalli, president of the pro American Basketball League. To each of these endeavors Jones would bring a charm on which marketing campaigns can be built.

To review: Win five golds, eclipse Florence Griffith Joyner and Jackie Joyner-Kersee in the record book, rescue track and field from oblivion, then nurture another sport by feeding Chamique from the point and maybe winning a few championships. This is heavy lifting, a job with few candidates. "I'll say this," says Dennis Craddock, who coached Jones during her moonlighting track seasons at North Carolina. "You don't put limits on what Marion Jones can do. In anything. Period." When Jones is finished, it might be fair to ask whether the best athlete in the world wears a jockstrap.

In the insular world of track and field, Jones's potential has long been known. An erstwhile California high school prodigy, Jones returned to the sport full time last year for the first time since 1993 (having forgone her final year of basketball eligibility with the Tar Heels) and stunned even her believers by winning the U.S. and world 100-meter titles and running 10.76 seconds for the 100, equaling the fifth-fastest time in history--all after one spring's crash training with a new coach. "We all knew she was fast, but we also knew it takes years to reach a high level," says U.S. sprinter Inger Miller, who ran with Jones on the gold-medal-winning 4x100 relay at last summer's world championships in Athens. "Everyone was shocked how quickly she hit those times."

On May 13 of this year, with a winter of training behind her, Jones ran 10.71, in Chengdu, China, the fastest 100 by any woman other than Flo-Jo. On May 31, at the Prefontaine Classic, she long-jumped a world-leading 23'11 1/4". At last week's national championships she became the first woman in 50 years to win three individual events--the 100, 200 and long jump--and she matched her 10.71 in the 100. "What she's getting ready to do is going to blow everybody's mind," says sprint coach John Smith, a 1972 U.S. Olympian in the 400 meters. "We're talking about 10.50 or better for the 100, 21-flat for the 200 [Griffith Joyner's world records are 10.49 and 21.34] and, in the long jump, at least 25 feet [Galina Chistyakova's world standard is 24'8 1/4"; Joyner-Kersee's U.S. mark is 24'7"]. I mean, as fast as she is--and she can dunk a basketball."

It's true, she can. "She's done it in practice, she's done it in warmups before a game," says North Carolina women's basketball coach Sylvia Hatchell. For the Tar Heels, Jones did much more than dunk. In her three years as starting point guard, North Carolina went 92-10, didn't lose an Atlantic Coast Conference tournament game and won the 1994 NCAA championship. At 5'10", 155 pounds, Jones brought explosiveness and speed to her position. "She intimidates when she walks on the court," says Hatchell. "And she brings everybody on her team up to her level, because she refuses to drop to someone else's. There's not a pro league in the world that wouldn't take her in a heartbeat."

This is how she affects others: In the 1996-97 basketball season, Jones's backcourt partner was sophomore Jessica Gaspar. In the second round of the NCAA tournament, as Carolina was eliminating Michigan State, Gaspar tore the anterior cruciate ligament in her left knee while slicing to the basket after receiving a pass from Jones. Gaspar didn't know for certain that Jones would give up her final year of eligibility, but she suspected it. "The first thing I thought was that this was the last pass I'd ever get from Marion," says Gaspar. "That hurt more than blowing out my knee, because I knew my knee would heal, but I wasn't ever going to play with Marion again."

Last summer, Jones soared to the top of the track and field world--supplanting Gail Devers and Merlene Ottey as the fastest woman in the world--even though her decisions to stop playing basketball and to marry 29-year-old shot-putter C.J. Hunter left her feeling unwanted by the North Carolina athletic community that she had so spectacularly represented and by her mother, whom she did not see for almost a year.

"I was not surprised by her performance," says Marion Toler, Jones's 52-year-old mother. "She was angry at people, at Coach Hatchell, at Coach Craddock, probably at me. She has always put critical articles in her scrapbook to motivate herself, and she excels in situations like this. There was a lot more at work last summer than fast-twitch fibers."

On the night of her 100-meter gold medal run in Athens, Jones stood outside the stadium in darkness and said, "As long as you're running fast, life is good." It's her mantra, her motivation and her escape.

They have lived a very long 22 years as mother and daughter. Toler came to the U.S. in 1968 at age 22 from her native Belize. She had previously spent two years at a secretarial school in London and spent two more in New York. She was briefly married and bore a child, Jones's half brother, Albert Kelly. After moving to Los Angeles in '71, she met and married George Jones, a union that lasted four years and produced one child, a girl born in '75 and named for her mother.

In 1983 the family moved from L.A. to Palmdale, a small desert city 50 miles to the north, and Marion married Ira Toler. While Marion Toler worked as a legal secretary, Ira played Mr. Mom to the children and became especially close to the girl known to her family and friends then--and to many of them now--as Little Marion. When Ira died of a stroke in '87, it was devastating to both Marions. "Ira was always there for my sister," says Kelly, now 27. "He talked to her, answered her questions, helped her with homework, took her to tee-ball games. Then he was gone."

As Little Marion grew, her drive became voracious. Kids on the block called her Hard Nails for her stoicism and spunk. "I had no use for dolls or any girl things or even girlfriends," says Marion, who loved snakes and wasn't afraid of the dark. Marion Toler, who had grown up with a father of Victorian sensibilities, understood that if she raised her daughter the way she had been raised, she would risk losing her. "She was the type of child who would say, 'If I don't get this or that, I'm going to jump off this ledge,'" Toler says. "If I said, 'Go ahead, jump,' she would have. I knew that she would defy me, test me, and there were many rebellions. But I decided that she was special, that I had to find a way to nurture these qualities, not beat them out of her."

The daughter's success and happiness became the mother's quest. Toler moved the family from Palmdale southwest to the suburban Los Angeles town of Sherman Oaks so Marion could attend Pinecrest Junior High. Before Marion's ninth-grade year, Toler and her children moved again, to the Ventura County town of Camarillo, and Marion attended Rio Mesa High. Two years later they moved once more, so Marion could attend and play basketball at nearby Thousand Oaks High. Toler worked two jobs one summer so Marion could go to Asia with a California all-star basketball team. In 1992 Toler enlisted Elliott Mason, who had once trained with five-time Olympian Evelyn Ashford, to coach Marion in her attempt to make that year's U.S. sprint team. (Jones missed by .07 when she finished fourth in the 200 and declined a spot as a 4x100 relay alternate because, she says, "when people come to see my gold medals, I want to be able to say I ran for them.")

Marion was a woman among little girls in high school. As a sophomore, she was the fastest in the U.S. at 100, 200 and 400 meters; as a junior she ran 22.58 for the 200, a national scholastic record that still stands. In basketball she twice took Thousand Oaks High to the regional championship game. How the soccer coach let her escape is a mystery.

Jones's self-reliance deepened as she grew. When her mother moved with her to Chapel Hill when she matriculated at North Carolina in 1993, Jones felt claustrophobic. "I had always been independent," says Jones, "but when I went to college, that was multiplied 10 times. My mother and I butted heads, a lot."

Toler says, "I wasn't trying to control her, I just wanted to watch her play ball."

Jones went to North Carolina on a basketball scholarship, with plans to run some track. "I loved track, and I wanted to keep it like that," she says. "So many young runners get burned out. I figured I'd do both, but in the beginning, I needed discipline, and the Carolina basketball program is very structured." Her basketball career was brilliant. It began with her standing at the top of the key--"Frozen," she says--when Charlotte Smith hit the three-pointer that gave the Tar Heels the 1994 national title and ended with a No. 1 seeding in the '97 NCAA tournament. (The Tar Heels were upset in the round of 16 by George Washington.)

Jones competed for two years in college track, always short of fitness, trying to sprint with a basketball body (as a full-time track athlete, her weight has dropped to a sinewy 148). In 1996 she had planned to redshirt in basketball and compete in the Atlanta Olympics. Had she not twice broken a bone in her left foot, derailing that dream, she might already have several medals.

It was in Chapel Hill that she met Hunter, who had won a bronze medal at the 1995 worlds. Hunter, seven years Jones's senior, was working as a throws coach under Craddock but resigned when he began going out with Jones in early '96, because university rules forbade coach-athlete dating. "Easy call," says Hunter. By the spring of that year, they were engaged.

Many people in the Tar Heels community were displeased that Jones and Hunter had paired up, and they blamed Hunter's influence for Jones's decision to forgo her last season of basketball and track eligibility. "There are a lot of people who care about Marion who feel that C.J. is not good for her," says Hatchell, voicing an opinion that Jones and Hunter have often heard.

Hunter comes with some baggage. He's the divorced father of two children and filed for bankruptcy five years ago. He's large and menacing and very economical with words. Says Jeff Madden, a former North Carolina strength coach and the man who introduced Jones to Hunter, "People are intimidated by him because he's blunt." This blunt: "People who criticize us don't give a damn about Marion," Hunter says. "Hatchell was thinking about her own team." (Point of fact: Hatchell's 1997-98 team had Tennessee down by 12 points with seven minutes to go in the Elite Eight, without Jones. With her, Carolina might have won another national title.) As to the notion that he is piggybacking on Jones's fame or wealth, consider that Hunter was an elite, world-class athlete before Jones was, and he is currently ranked No. 2 in the U.S. in the shot. His Nike contract came first. "If I'm so bad for Marion, look what's happened since we met," says Hunter. "She had her best academic year, and she's become one of the most popular athletes in the world."

Jones stopped training at North Carolina, and she and Hunter closed the circle tightly around themselves. "When you try to keep two people apart, what happens?" asks Hunter. "They get closer." In Jones's last basketball season, Hunter sat in the stands through every practice and monitored every interview. He set her up with his agent, Charlie Wells, and a coach, Trevor Graham. On the European summer circuit they are inseparable and, often, invisible. "You almost never see Marion outside of her room on the circuit, and if you do, she's with C.J.," says Miller.

Where others saw seclusion, Jones and Hunter felt something else. "I've never in my life had somebody whom I could tell everything to," says Jones. "Now I can. I have a companion." She also has what her mother once was: a shadow to her every move. She also appears to have bliss.

Joyner-Kersee, into whose shoes Jones is stepping (as the best female track and field athlete in the world and as a two-sport star), has observed this soap opera from afar. She knows that the comparisons between her and Jones don't end with sports but extend to their relationships with men who have taken charge of their personal and professional lives. "There are plenty of people who have never liked me and Bobby together," says Joyner-Kersee of her husband and longtime coach. "It doesn't matter. Marion and C.J. are a partnership. It's their life, and outsiders don't matter."

Toler is one who has been pushed to the outside. She hosted a graduation party for her daughter on May 11, 1997, then didn't hear a word from her until a phone call just before Christmas, although Jones sent postcards from Europe last summer. "We're not close," Jones said in early April. "We're not on the best of terms."

It's true that Toler is apprehensive about the impending nuptials, scheduled for Oct. 3, but this is hardly unprecedented for a mother-in-law-to-be. "I can't say this is how I wanted it to be for my daughter," says Toler. "A divorced man with two children. Is C.J. right for her? I pray that he is. She is in a little girl's world, with her audience and her celebrity, and my take is that she is looking for her daddy. C.J. comes across as a protector, but in truth, nobody can protect you until you grow up."

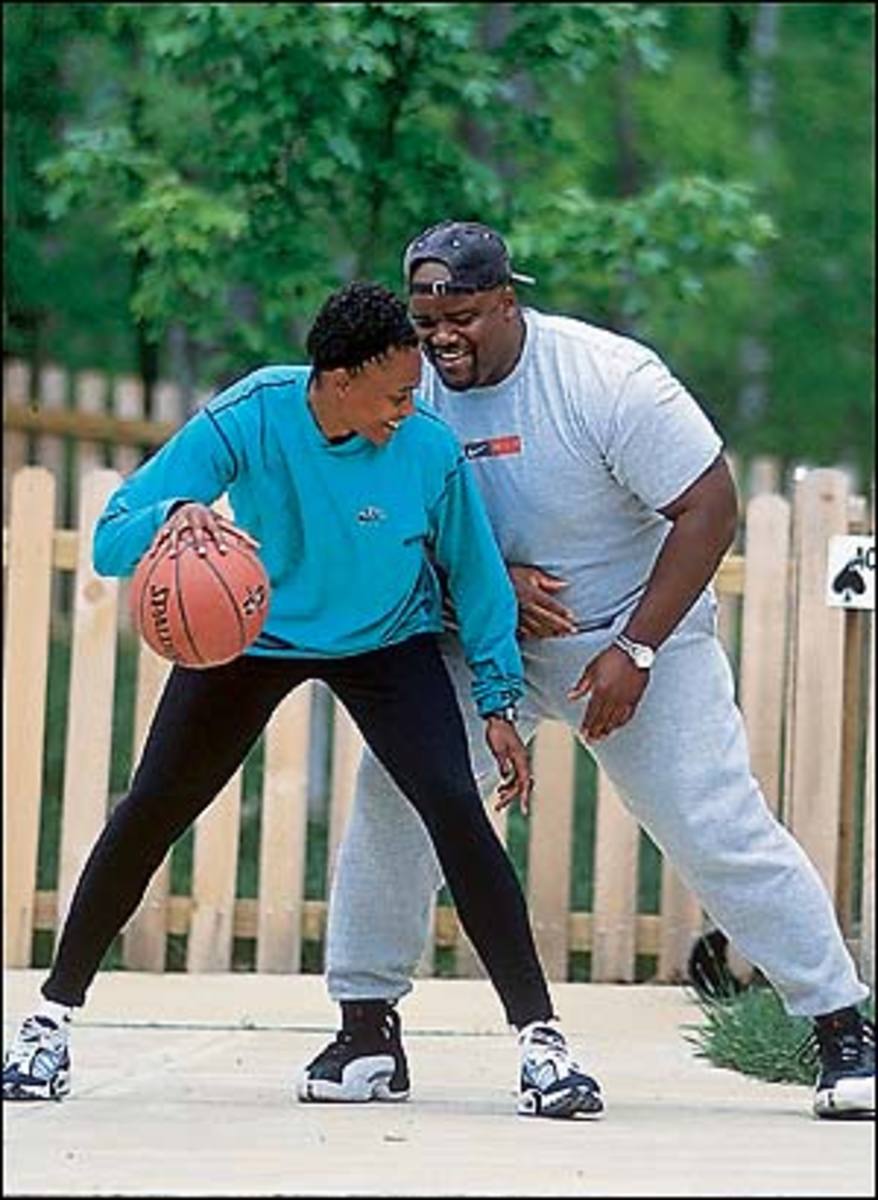

Their new four-bedroom house sits at the end of a cul-de-sac in the upscale neighborhood of Apex, midway between Raleigh and Chapel Hill. There's a hoop in the driveway, where Marion can crush C.J. in games of H-O-R-S-E and where C.J. can back Marion down and post her up. When C.J. returns from his workout this afternoon, Marion is flopped on the couch watching The People's Court. They live the streamlined existence of full-time athletes pulling down more than $1 million a year in prize money and endorsements. A typical day at home, says C.J., is "training, a nap and Judge Judy."

On occasion they socialize with C.J.'s coach, Brian Blutreich, and his wife, or with some of Jones's former basketball teammates. More often they stay home and challenge each other in video games. They recently bought a women's college basketball game, but neither is allowed to play as North Carolina, and Tennessee might as well not be on the disc. "No orange in this house," says Marion. C.J.'s passion is Notre Dame football, and he keeps dozens of game tapes in the family room. There's a sense of satisfaction in the air, a feeling that C.J. and Marion describe with a catchphrase: "What a difference a year makes."

In the spring of 1997, after deciding to turn pro, Jones needed a plan. Initially, she intended to run a little track, then play in either the ABL or WNBA. First, though, she needed a coach. Hunter had been working with her, but, he says, "that's the same as saying she wasn't being coached at all."

One day, as Hunter worked with Jones at North Carolina State, Graham stood on the other side of the track, watching. A silver medalist on Jamaica's 4x400-meter 1988 Olympic relay team, Graham was now trying to build a coaching franchise by working with the likes of former world 400-meter champion Antonio Pettigrew and devouring manuals on technique. "Here I'm getting all this knowledge," Graham says, "and I just needed a great sprinter so I could teach it."

Looking across the track that morning, Graham was thunderstruck. "I thought, Oh, my god, Marion Jones," he says. It was as if Graham were a physics tutor and little Stephen Hawking had walked into his classroom. When Hunter called out, "Trev, what do you think?" Graham replied, "Mind if I fix something?" He made one small adjustment, then another, and Jones instantly ran faster and smoother. "It was, like, automatic results," she says. "That had never happened to me. Trevor changed little things, like the angle of my blocks or the way I carried one arm, and I improved immediately."

Pre-Graham, Jones had run a wind-aided 11.51 at the Florida Relays. Three weeks later she ran a legal 11.37 (and long-jumped 21'8"), followed in succession by a wind-aided 11.19 and 10.97. The phone started ringing with offers from meet promoters in Europe. Basketball was dead for 1997, buried beneath the sudden possibility of a cascade of gold medals and world records, and far greater earning power than the WNBA or ABL could offer.

"I don't know what she can't do," says Joyner-Kersee. "She's gifted and she's mentally tough. She can own everything from the 400 on down, plus the long jump."

Most intriguing will be her assault on Flo-Jo's records in the 100 and 200, marks viewed with reverence--and suspicion--in track and field. The suspicion stems from the near-certainty that Griffith Joyner's 10.49 in the 100 at the 1988 Olympic trials was heavily wind-aided and from the fact that all her best times were run in a one-season flash of brilliance that she never again approached. Jones is the first woman in a decade to regard Griffith Joyner's times as being within reach. "The majority of women in sprinting have acted like those records can never be broken," says Jones. "So they haven't pressed to go fast. I'm 22 years old; I'm going to get faster. Before my career is over, I will attempt to run faster than any woman has ever run and jump farther than any woman has ever jumped."

As she ascends, Jones can broaden the appeal of her sport with a smile and a sound bite. "She's like a movie star," says Hatchell. "Whatever mood she's in, she can turn it on for the cameras." Agent Brad Hunt says, "She has both athletic ability and charisma. That's rare in track and field. It's what sets her apart." Two of Hunt's clients, Michael Johnson and Gwen Torrence, possessed consummate athletic skills but minimal ebullience. The same was true of Carl Lewis. Jones's stage presence will translate splendidly to her other beloved sport, of which she says simply, "I'm a basketball player who has put it off for a couple of years."

This is a huge job for one woman, with anger and rebellion as her principal motivations. This spring the ice began to melt. Toler returned to North Carolina for eye surgery in April, and to her surprise, her daughter visited her every day then spent a week at her mother's Houston home in May. After the reunion Jones offered a new view of their relationship. "My mother and I love each other very much," she said. "I'd do anything for her and vice versa. If at the end of my life I can say that I was just a quarter of the woman she has been, I will be satisfied."

On one of those days they spent together in North Carolina, they took a ride in Marion's Jeep. As they rode, Marion handed her mom a check. "A big check," says Toler, whose heart sank. "Marion," she said, "I don't want your money, I just want a relationship with you." Jones stared ahead, unflinching, until tears, so rare for her, began to form in the corners of her eyes. "Two tears fell," says Toler. "Bop, bop. Just two. Then she said, 'Mom, I want you to have it.'"

A red carpet lies at Jones's feet, dotted now with tears. Perhaps soon the fastest woman alive will run not from anger at bitter coaches or lost fathers, but from the joy of speed and transcendent physical gifts. Two tears. It is a start.

Issue date: June 29, 1998