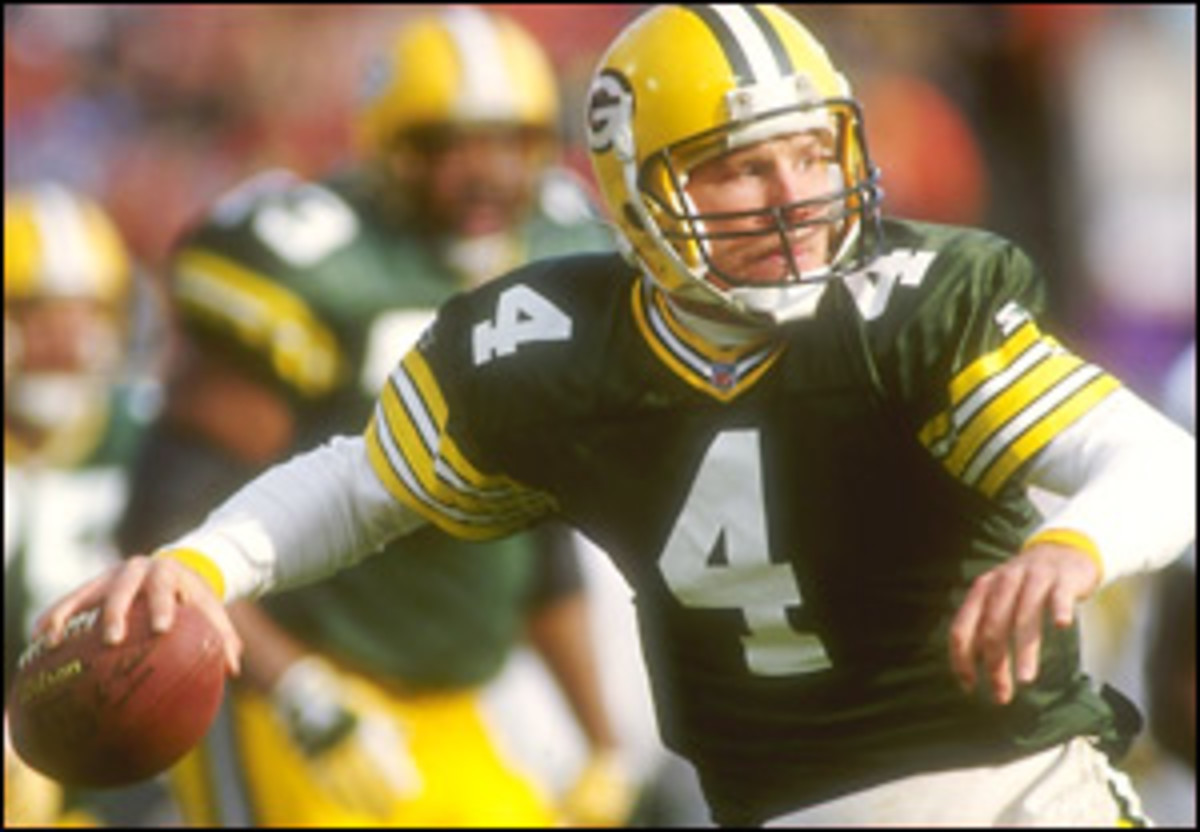

SI Flashback: Leader of The Pack

This story originally appeared in the Aug. 23, 1993 issue of Sports Illustrated.

Brett Favre is looking for a clean golf shirt. Two clean golf shirts, actually. He is flying in the morning to Pittsburgh, and that afternoon he is playing golf at Oakmont Country Club and the day after that he is playing in one of those celebrity benefit things at some other Pittsburgh course. His agent has told him that playing at Oakmont is a big deal. The U.S. Open is played sometimes at Oakmont. To move around a course that famous, a man should be dressed right. The agent is worried that Favre may not be dressed right. The agent knows Favre.

"I think about golf and I think about wearing a T-shirt and cutoffs and sneakers," Favre says. "You know what I mean?"

A golf shirt. ...

A golf shirt. ...

He is looking through piles of clothes, looking through drawers, looking around and around his room. His room? It is a room from the pages of Boys' Life. Sports posters and pennants and memorabilia cover the walls and the ceiling, Charles Barkley dunking next to Joe Montana, who is passing a football, next to a program from the 1982 Sugar Bowl that actually was signed by a collegiate Dan Marino. A picture of Bear Bryant is placed directly above a picture of Jesus Christ. Priorities, perhaps. Bear Bryant is the one wearing the checkered porkpie hat.

"Is this all right?" Favre asks, pulling out a blue golf shirt from one of the piles.

"Is it yours?" his mother, Bonita, asks.

Who's to say for sure? Who knows? The three Favre brothers live in this room -- O.K., their room -- and the shirt could belong to any one of them. It also could belong to their father, Irvin (the Hammer), or maybe to their sister, Brandi, the reigning Miss Teen Mississippi, or maybe to their aunt, Kay-Kay, or maybe to Bonita or maybe to just about anyone in Hancock County. There's a kid named Clark who has been living in the house for a few weeks now, and Jeff, the youngest brother, back just today from his freshman year at Southern Mississippi, in Hattiesburg, has brought a friend to stay for a few days, and a kid named Mark has been around all day and ... who knows? Laundry is a problem.

"Brett was wearing my shirt one day," Kay-Kay says. "I told him it was mine. He said it was his. I said, 'Well, that must be true, because you look awfully good in a T-shirt with shoulder pads. . . .' "

"Everybody just wears everybody else's clothes in this house," Bonita says. "It gets confusing. One time I just wrote names on everything, to try to keep down the fights. Well, Brett calls us from Green Bay one day. He got undressed in the locker room. Seems that the word DAD was written across the top of his underpants. ..."

Blue. Brett decides the shirt must be his. Couldn't be anyone else's. He throws it into his traveling bag. Now he needs to find only one more shirt for the trip. Why is the outside world so complicated? A golf shirt to play golf.

***

The house is on Irvin Farve Road in Kiln, Miss., a dead-end dirt road that finishes at a still stretch of water called Rotten Bayou. On a hot day, of which there are many here, a visitor arrives in a small tornado of red dust. Almost 10 years ago the road was named after Brett's dad, which seemed logical since he was the local high school football and baseball coach and no one but Favres and their relatives lived on the road anyway. The sign was misspelled, which is not so bad because that is the way the name is pronounced. People can figure it out.

As for Kiln, the n is dropped by local speakers. The town of 7,500 residents usually is called the Kill. The question would be "Where does the hottest young quarterback in the NFL live in the off-season?" The answer would be "The Kill." People can figure it out. This is home.

"People say, 'You're the quarterback of the Green Bay Packers and you still live at home?' " Brett Favre says. "Well, I could be other places, but I can't think of one I'd rather be. Where else could I have so much fun? That's what this is all about. Having fun."

He is 23 years old and as uncomplicated as a Sunday afternoon. Natural. Where else could he fall out of his water bed every day and land in a family party? His grandmother Mee-Maw lives in that little trailer down the road and makes the best gumbo on the Gulf. (Mee-Maw's real name is Izella French, but Brett and his brothers began calling her Mee-Maw and their other grandmother Maw-Maw when they were little. The names stuck.) There always is someone around who will play a little golf or maybe go over to Biloxi or Gulfport and do a little gambling on one of those new paddleboat casinos. There always is someone around to have a beer, to start a barbecue. Where else is every day the Fourth of July?

"I remember the first long trip I made," Brett says. "Senior year of high school. The class trip. We went from here to New York and Boston. We raised the money ourselves with all kinds of projects. I went to a restaurant, a sandwich place in Boston. The guy said, 'What'll you have?' I told him I guess I'd have a shrimp po'boy. He just looked at me. I tried to explain what a shrimp po'boy was. I wound up with a submarine sandwich."

The wheels and gears of the Great American Celebrity Machine only now are starting to turn. There has not been time yet to turn him into a 6 ft. 3 in., 220-pound plastic package, to make him accustomed to limousine living and large sums of money and everyday fame. Everything is still new. He basically has had one electric season in the NFL, last year, when he came off the bench for the Packers in their third game and never sat down again, rejuvenating the team, at one time passing for more than 200 yards in each of 11 straight games. The team missed the playoffs only on the final Sunday. He wound up in the Pro Bowl. He showed again and again that he could throw the football. Then he came home.

"Reporters would ask me where I got my arm," he says. "I always thought it was from my father, but now I think I got it from my mother. She got mad at me last summer and threw a pastrami sandwich and hit me in the head. Hard. She really had something on that sandwich."

"I was really mad," says Bonita, who is a special-ed teacher at Hancock County High. "I was running the four swimming pools in the area, in charge of 12 lifeguards. They were driving me crazy, the lifeguards. I told all of them if it started to rain, I would call and tell them whether or not to close the pools for the day. I told them not to call me. I would call them. Well, it started to rain, and this one lifeguard calls me. I was just fuming, and Brett, he's sitting in the kitchen just laughing at me. I had this pastrami sandwich in my hand, and I just let it go, mustard and bread flying all over the place. ..."

"I didn't even know what pastrami was," Brett says. "Except that it hurt."

The good things that happened in Green Bay and in assorted other stadiums around the country still seem almost touched with magic. The idea that anyone could come from here -- this little place six miles from the Gulf of Mexico, where an occasional alligator pokes its head from the bayou -- and wind up famous is borderline fantasy. The Packers virtually have handed their team to Favre. They dumped his competition, Don Majkowski, the hottest young quarterback of three years ago, and brought in veteran Ken O'Brien from the New York Jets to add experience and counsel. They went heavy on the free-agent market this off-season, winning the big-money chase for defensive end Reggie White. They are making a run for a division title, making it with a kid quarterback.

This is a different situation for Favre. For the first time in his life he is not an underdog. "I've always had to struggle for what I've got," he says. "I was never recruited for college. No one really wanted me. Coming from down here, nobody knows who you are. Three days before the signing date, I was going to either Pearl River Junior College or Delta State. Southern Miss took me as a defensive back. When I went there as a freshman, I worked out both ways at first. I was the seventh quarterback on the depth chart."

Seventh on the depth chart? He was third by the time his freshman season started. He was playing by the second half of the second game, throwing two touchdown passes to beat Tulane. On his 18th birthday he was starting against No. 1-ranked Florida State, the Florida State fans singing a derisive Happy Birthday as his team was pounded by the Seminoles 61-10. He was on his way.

"Southern Miss was a place where everyone had been rejected by the big schools for some reason," he says. "We were the Island of Misfits. We thrived on that. We'd play Alabama, Auburn, and there'd be stories in the papers about how we'd been rejected by them. We'd come out and win the game, and guys would be yelling on the field, 'What's wrong with us now?' It was a great way to play."

As his senior year approached, he was known as a fearless kid who could throw the ball. The Southern Miss offense had been redesigned for his talents. He had completed 79 passes for 1,264 yards and 15 touchdowns. The pro scouts were interested. He was ready for big things. Then he flipped his Nissan Maxima and almost killed himself during the summer before that senior year.

The accident happened in the Kill, less than a mile from his house. Returning from a July afternoon of sun and, sure, fun at Ship Island, he says he was blinded by the lights of another car. He swerved and hit gravel, and when he tried to pull the car back onto the road, it began to flip. His brother Scott was following in another car and later reported that one flip was so high "you could have driven a dump truck underneath the car." Scott broke the front window with a golf club to pull Brett from the wreckage. Brett wound up in the hospital with a concussion, lacerations and a cracked vertebra and, it turned out, complications.

"I was out of the hospital, and I thought I was O.K.," Brett says. "I wasn't eating much, though, and when I did I was throwing up. I kept having these abdominal pains, and they started to get worse. I went back to the hospital, and they found that a lot of my intestines had died."

Thirty inches of intestines were removed. His recovery had to begin all over again. He reported to Southern Miss in mid-August but still was having trouble eating. Back he went to Kiln, where Mee-Maw's cooking finally got him going. Five weeks after the intestinal surgery he was at Southern Miss again, in uniform, 30 pounds underweight, leading the Golden Eagles to a 27-24 upset over Alabama.

"You can call it a miracle or a legend or whatever you want to," Alabama coach Gene Stallings told reporters afterward. "I just know that on that day, Brett Favre was larger than life."

The Eagles finished the 1990 season at 8-4. Favre, who never was 100% recovered from the surgery, ended up in the Senior Bowl and the East-West Shrine Game. At the Shrine game he more than caught the attention of Ron Wolf, then a scout for the Jets. After the accident a lot of scouts had dropped Favre in their thinking. Wolf still liked the way he threw the ball and also liked the way he took charge, the way he had that gift of making everyone else in a huddle listen and respond. How many leaders does a scout see?

Alas, the Jets already had lost their No. 1 draft pick by signing Syracuse wide receiver Rob Moore in the supplementary draft. Their first choice was in the second round, 34th overall. The Atlanta Falcons picked Favre with the 33rd pick and gave him a three-year contract worth $1.2 million. It wasn't until the next year, when Wolf had moved along to become the Packers' general manager, that he finally could make his move. On Feb. 10, 1992, Wolf traded the Pack's first pick to Atlanta, for which Favre had thrown only five passes all season playing third-string. Wolf was told he was crazy.

" 'Have your lost your mind?' was what most people said," Wolf says. "I just really liked him. He has that unexplainable something about him."

The '92 season turned out better than Favre or even Wolf could have expected. When Majkowski went down with sprained ligaments in his left ankle, the prognosis was that he would miss two weeks, maybe four. Favre came into the lineup, won two games and simply rolled. Natural. He finished with 302 completions for 3,227 yards and 18 TDs. He was sixth in the league in completion percentage, third in interception rate.

He also showed durability and resourcefulness. In the first half of his seventh start his left shoulder was separated in a hit delivered by White, then with the Philadelphia Eagles. It was a brutal play. Favre had thrown his pass and could see the collision coming. He turned his body to absorb it. White grabbed his hand and yanked him back the other way to make him vulnerable. The two men landed together. Favre's shoulder was the point of impact. It was a play designed to do what it did -- to hurt him, hopefully to put him out of the game -- not to stop the pass. He stayed in the game, shot up with a painkiller at halftime, but could not lift his arm as high as his shoulder and could not hand off to the left. The Eagles and the rest of the teams on the Packers' schedule saw his difficulty and worked on it. The shoulder hurt for the rest of the season, but he still played.

"Now Reggie's with us," Favre says. "I talked with him at minicamp. He said he thought for sure he had put me out. I told him I just about thought he had too. Then he put his arm around me. He told me not to worry, that this year we were on the same side. I liked that."

The shoulder, still healing, still hurts. It should be better by the start of the season.

***

"Sports Illustrated," Favre says, packing for the trip to Pittsburgh. "In my junior year a writer came down to Southern Miss to do an article for Sports Illustrated. He said he wasn't sure the article would be in, but if we beat Florida State in our opener, he was pretty sure it would make it. We go out. We pull the upset. All I'm thinking about the last few minutes on the field is, God, I'm going to be in Sports Illustrated."

The article never appeared -- Southern Miss went on a four-game losing streak after the upset -- but so be it. Sports Illustrated. He will be in there now. It will mention the new house he has added to the colony on Irvin Farve Road. Though there is an apartment on the second floor that he will use sometimes, it is not his house. It is a family house. A party house with a swimming pool. It has changing rooms, a big-screen TV, a pool table and video games, a room with a Jacuzzi, a full kitchen to prepare party foods and a deck large enough to hold as many people as might show up at any one time.

"We've already had parties there," Favre says. "Nothing planned. They just happen. A couple of weeks ago we started on Thursday, and by Saturday there were over 100 people on the deck."

This night's plans seem to be taking shape. Favre is going to New Orleans, where he will take a hotel room so he can make his 6:30 a.m. flight to Pittsburgh. Clark, the friend, is going along for the ride to New Orleans and to spend the night partying. Mark, the other friend, also is going. Jeff, the younger brother, is not going. Back from college, he is going to look around the area for some friends and some action. Scott, the older brother, also is not going, because he is in Hattiesburg taking a real estate course.

Bonita is going down to Mallini's Point Lounge in Pass Christian with Mee-Maw and Mee-Maw's boyfriend. Once he gets cleaned up after a late dinner, Irvin will join them. Mallini's once was owned by Mee-Maw's late husband, Bennie French, who was a local rogue of sorts, a man who managed boxers and had a speakeasy and ran whiskey off the Gulf Coast for Al Capone. Bonita and Irvin once worked at the bar, and Brett and Scott rode their Big Wheels around the pool tables when they were young. Kay-Kay is staying home because she has to go to work early in the morning. Brandi, Miss Teen Mississippi, also is staying home. She is 16 and says she has a lack of dates because Brett and her other brothers say they will seriously injure any date who comes to the door.

Perhaps Brett's own experience has educated him in this regard. He has a four-year-old daughter, Brittany, with Deanna Tynes, whom Brett has been dating since ninth grade. Brittany stays at the house every day while her mother works. Deanna is getting Brittany ready to go home. It is not an awkward situation. In fact, it is quite pleasant. Everyone is making a fuss over Brittany.

"Why would I want to be anywhere else?" Brett says from the middle of the activity. "Why?"

He says he will be home in two days. He has made only two golf commitments for the entire summer, this one and a later tournament in Milwaukee named in honor of Vince Lombardi. The Lombardi tournament makes him nervous. He says that Packer coach Mike Holmgren, who played last year, said the fairways were lined with spectators. What if they are lined with spectators this year? Favre says he is sure he will hit one of them on the noggin and that the ball will be traveling fast. Favre says that Holmgren was in control of his nerves at the beginning of last year's tournament, but he was paired with Leslie Nielsen, the actor. Nielsen had one of those whoopee cushions, and he made the sound of breaking wind whenever Holmgren was close on the first tee. The coach was nervous the rest of the day. "All I hope," Favre says in a down-home Southern accent, "is that I'm not playing with Leslie Nielsen this year."

On to Pittsburgh. The outside world awaits.