End of an era

In the spring of 1949, Tommy Lasorda saw Dodgertown for the first time. "Except I couldn't see anything at all," Lasorda said. "I walked through the gates at 10 at night. The place was so dark, you couldn't see a thing. There wasn't one light on. I was scared to death. I was just a 21-year-old kid, an aspiring left-handed pitcher, who didn't know where I was or where I was going or what would end up happening to me."

The next morning, the sun came up, and he got his first glimpse of this strange but charming little town on the Florida coast. "I saw Jackie Robinson, Duke Snider, Gil Hodges, Pee Wee Reese," Lasorda said. "They were just walking around like normal guys. At night, they'd eat in the dining room, play cards in the barracks, and shoot pool."

Five years later, when Lasorda made his major-league debut, Robinson recognized him from Dodgertown. "I had a couple guys on base at one point and Jackie came to the mound," Lasorda said. "He told me: 'Relax, you're doing okay, everything's going to turn out all right. Just let him that ball on the ground and I'll take care of it.'"

In the middle of his own story, Lasorda stopped for a moment: "You know," he said. "They can take us out of this place. But they can't take away these memories."

This week, the Dodgers finally leave Vero Beach, Fla., 60 years after they arrived. They will turn down Sandy Koufax Lane and Vin Scully Way, headed west for the last time. They are spending the final week of spring training this year in Phoenix, and starting next season, they will move into a glimmering new complex in Glendale, Ariz.

Of course, baseball teams switch spring-training sites all the time -- but not this team, and not this site. For more than a half-century, Dodgertown was synonymous with spring. A fan could lounge under palm trees on the outfield berm, talk to players sitting in open-air dugouts, and watch other aspiring young pitchers warm up in Campy's Bullpen, named after Hall of Fame Brooklyn catcher Roy Campanella. The place was campy, sure, but it was charming. Even the streetlights were fashioned to look like little glow-in-the dark baseballs.

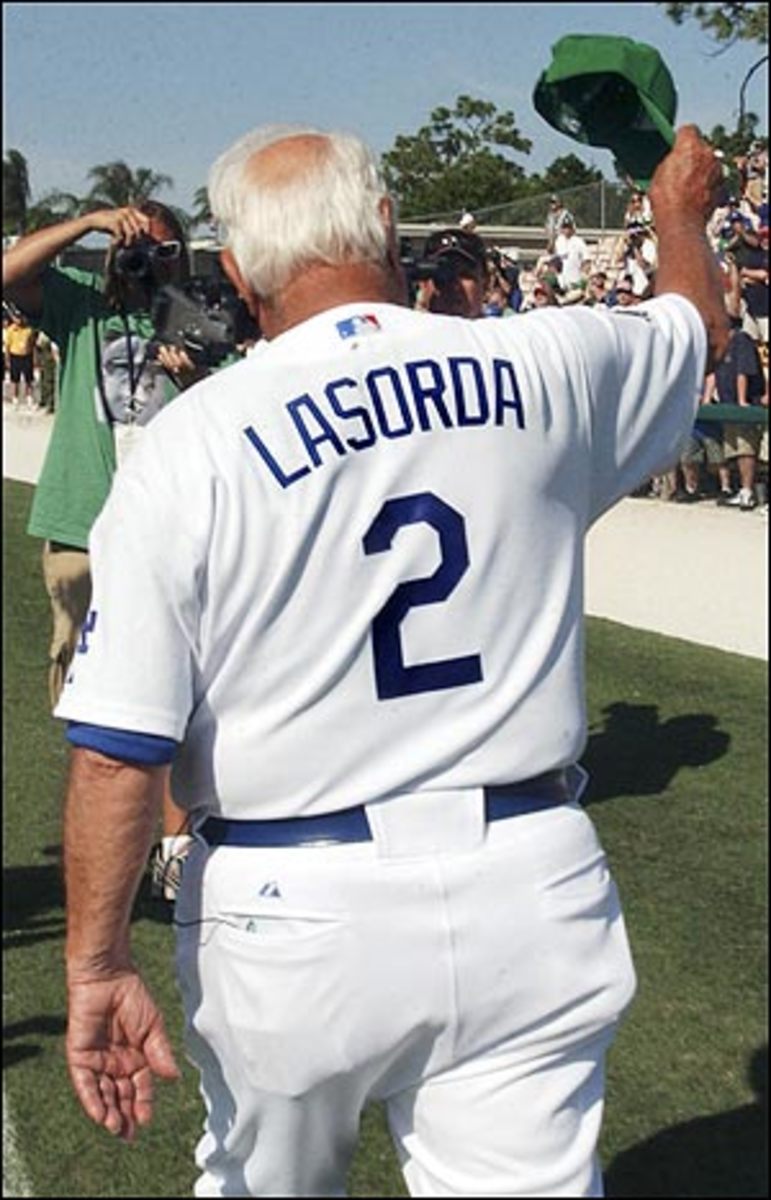

If Dodgertown was a baseball Disneyland, Lasorda was its Mickey Mouse. Considering that spring training lasts about six weeks every year -- and Lasorda missed only a few springs since Dodgertown opened in 1948 -- he has spent about seven years of his life as a resident of Vero Beach. Even now, at 80, more than a decade after he managed his last major-league game, he dresses in full uniform every morning.

Last week, the uniform was actually necessary. In one final nod to the past, the Dodgers asked Lasorda to manage the team for its last week in Vero Beach. Joe Torre is off in China, a new frontier for baseball, managing a Dodgers' split quad.

Lasorda has a formal position with the Dodgers, as advisor to chairman Frank McCourt. But he has also served as the organization's unofficial ambassador to Florida. He is the one who greets fans, recommends restaurants, and marvels at the new construction down by the beach. As a traditionalist, he loves this place like a second home. But as a realist and a Californian, he recognizes that it is time to leave.

"To be honest," Lasorda said, "I often wonder why we didn't move sooner."

When the Dodgers played in Brooklyn, Vero Beach made perfect geographical sense. Every spring, snowbirds from New York would fly non-stop to South Florida, eager to thaw out and see their team. When the Dodgers moved to Los Angeles in 1958, many Brooklyn fans continued rooting for the club and making the annual pilgrimage.

"But those fans are gone now," Lasorda said. "We have to think of our fans in Los Angeles. They want to come to spring training, too. They want to watch us play, too."

Games in Vero Beach start at 10 a.m. PST. Flying there from Los Angeles takes an entire day, and sometimes part of the night. During March, budget hotels off the freeway can run close to $200 a room. By contrast, in Glendale, games will start at 1 p.m. PST. Flying there will take about 90 minutes. Fans can stay in any hotel in Phoenix.

"It's sad," Lasorda said. "But it has to be done."

The new complex in Glendale will cost $80 million, and compared to the one in Vero Beach, it will feel massive and impersonal. In other words, it will probably be a lot like Legends Field in Tampa, the Yankees' spring home. Lasorda wonders if fans will still be able to walk with players from station to station, snapping pictures as they go.

The Dodgers may have outgrown Dodgertown, but baseball has not. The Baltimore Orioles have been in negotiations to move their spring-training site from Fort Lauderdale to Vero Beach. It would be bizarre to see another team in Dodgertown -- sleeping in the Dodgers' housing units, playing on the Dodgers' tennis courts, eating at the Dodgers' barbecue pit, jogging on the Dodgers' trails, relaxing in the Dodgers' theatre -- but then again, it would give Lasorda an excuse to come back and tell stories.

"When I was managing, there were many times that a game went to extra innings and we didn't have any players left," Lasorda said. "But in Dodgertown, a lot of the minor-leaguers would stick around and watch the games. So I'd just go right into the stands, grab one of those young guys, and tell him to go put a uniform on.

"I just don't know if that happens anywhere else."