Davis Phinney celebrates his biggest win (so far)

Last month I wrote about America's First Family of cycling. Its handsome, hard-luck patriarch is Davis Phinney. One of the greatest riders in American history, he was diagnosed eight years ago with young-onset Parkinson's Disease. He's battled ferociously since then, but the Body Snatcher (his coinage) has taken its toll.

Well, the guy whose motto is "Celebrate small victories" just celebrated a huge one.

A few days after the SI story came out, Phinney took the first step in a procedure called Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS). After sawing a pair of openings in his cranium, doctors installed two tiny electrodes into a region of the brain called the subthalamic nucleus. Once there, ideally, the electrodes would carry impulses to block the abnormal nerve signals causing his tremors.

A couple days later he underwent a second procedure. A pacemaker was implanted in his chest, with a cable snaking its subcutaneous way up the right side of his neck and skull, where it was then attached to the electronic "leads."

Phase 3, and the moment of truth, came last Friday. That meant that he had to go off his meds on Thursday, resulting in one of the longest nights of his life. "I didn't sleep because my [left] hand wouldn't stop tremoring," he recalls. "I was laying there, pinning it in various positions, and thinking, 'I just wanna sleep.'"

The shaking intensified at Stanford University Hospital, where Davis was first subjected to a battery of physical tests to establish his "baseline parameters."

"I was gyrating at 180 rpms," says Phinney. "I was a whirling dervish. It was definitely one of those moments where I told myself, 'OK, just suck it up. If I could get through seven hours in freezing rain at the '85 Milan-Torino, I can get through this.'"

When the pacemaker was activated, doctors still had to determine the ideal settings, through trial and error.

Finally, he recalls, "they hit the sweet spot and it was just like this 'WHOOSH!" and the tremor just ... stopped." His left hand and arm were still. "My whole left side, which had been so rigid, relaxed. It was a wave of total relief."

At one point Davis noticed that his wife, Connie, was in tears. "Why are you crying?" he asked.

It was if he'd been "encased in armor," she told him, "And the light in your face just came on again."

Davis won 328 races in his career, and married a woman whose feats on the bike were, in some ways, more impressive than his own. Connie Carpenter-Phinney won a dozen national championships, four world championship medals and an Olympic gold.

(After she explained the rules of individual pursuit to me at a velodrome in California last January, I asked her, "Did you ever compete in this event."

"Yes," she said, matter-of-factly. "I was world champion.")

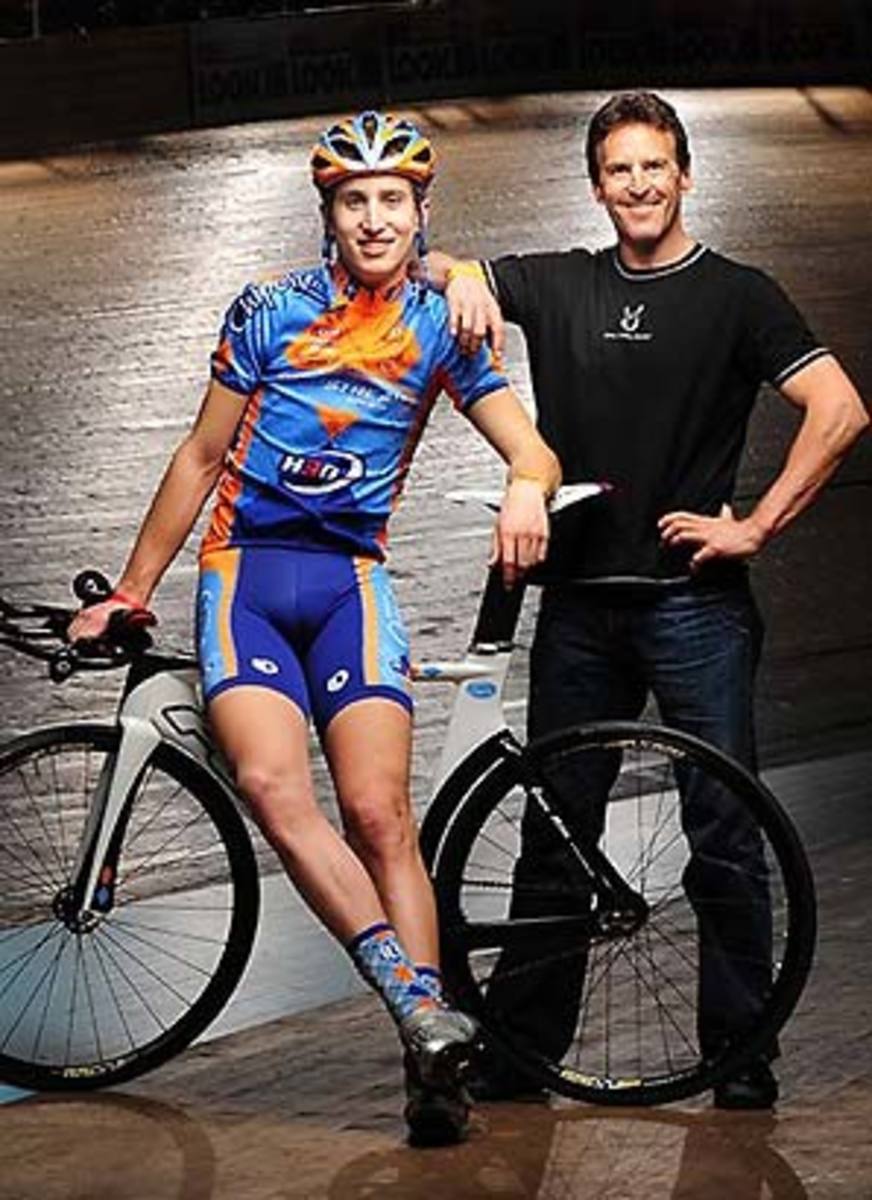

So it's less than stunning that Taylor Phinney, now 17, has emerged as the most promising talent to come on the U.S. cycling scene in recent memory. In his second season of racing, in '06, Taylor became the world junior time trial champion. This year, his first riding on the track, he finished the season ranked third in the world in the individual pursuit -- an event he'll contest at the Beijing Olympics. Which, thanks to the success of his DBS, Davis will witness in person.

Taylor won't be blazing new ground for his family. Davis won a bronze at the '84 Games in L.A., where he was outshone, incidentally, by his wife, who capped a spectacular career by winning gold in the women's road race.

Her physical strength has been beggared, since Davis's diagnosis, by the strength she has shown in supporting him. What has this woman had on her plate? Let's see: helping a husband with full-on Parkinson's while raising two teenagers -- 13-year-old Kelsey and her older bro, the Olympian -- and running hers and Davis's bike camps.

She has shouldered her burden with equanimity, grace and excellent humor. Another huge upside of Davis's successful surgery is that Connie's burden has been lightened, too.

While the tremors are not reduced to zero, Connie wrote in a good news e-mail, "They are markedly (let's say 90 percent) reduced ... Even was the return of the brightness of his eyes and the intensity of his smile."

Through his speeches and foundation, Davis has taken a leading role in helping those afflicted with PD -- "my tribe," as he calls it -- reclaim their lives. Just because there's no known cure for the disease need not stop them from experiencing "curative moments -- small victories when we're not thinking about PD because we're purely happy right now."

Davis gave a shout-out to Medtronic, the company whose hardware "that's given me a new lease on life." So dramatic is the difference that Davis is now having to unlearn behaviors he adopted to cope with PD. "You learn how to protect yourself, to not stand out, to get by one-handed -- like putting my hand in my pocket" to still the shaking." Suddenly, his coping techniques are unnecessary.

The procedure didn't cure him. As of yet there is no cure for Parkinson's. What it does, says Dr.Jaimie Henderson, the Director of Stereotactic and Functional Neurosurgery at Stanford, is "turn back the clock about five years."

Davis, of course, believes he'll milk it for much longer than that. The bottom line is this gives him and his foundation that much more time to raise funds, awareness and hope. Who knows what breakthroughs are on the horizon in the fight against the Body Snatcher?

"I keep thinking it's going to wear off, like my medicine would," says Davis, a day after the switch was flipped. "And it's not."

He can't walk through metal detectors at airports anymore: they could switch off the battery in his pacemaker. That means intensive patting down every time he has to catch a flight. (In Phinney's eyes, it's kind of a wash. When he was in the throes of Parkinson's, Davis was usually selected for extra screening anyway. "It doesn't look right that I would be nervous and shaking," he says, "so they figure I'm a drug addict or a terrorist."

Should the pacemaker be turned off, doctors gave Phinney a "remote" that can reactivate it. Not that you'll find the remote on Phinney's actual person. Connie keeps it. "If I give it to him," she says, "he'll lose it."

I spoke to her on the phone on Sunday afternoon. She was gardening. Her husband was grabbing a nap -- making up for years of shallow, interrupted sleep.

All the sudden, says Connie, "he's got all these muscles firing that haven't been firing for awhile. He's not used to it."

What had Davis done to tax those long dormant muscles? He'd been out on a bike ride.