The trend of players choosing a college before a high school

Howard Avery uttered those two words into his phone last Monday after Kentucky basketball coach Billy Gillispie offered Avery's son, Michael, a scholarship. Avery had called to follow up on an encounter with Gillispie at a LeBron James-sponsored tournament in Akron, Ohio, the previous weekend. NCAA rules forbade Gillispie from discussing Michael's play with Avery at the tournament site.

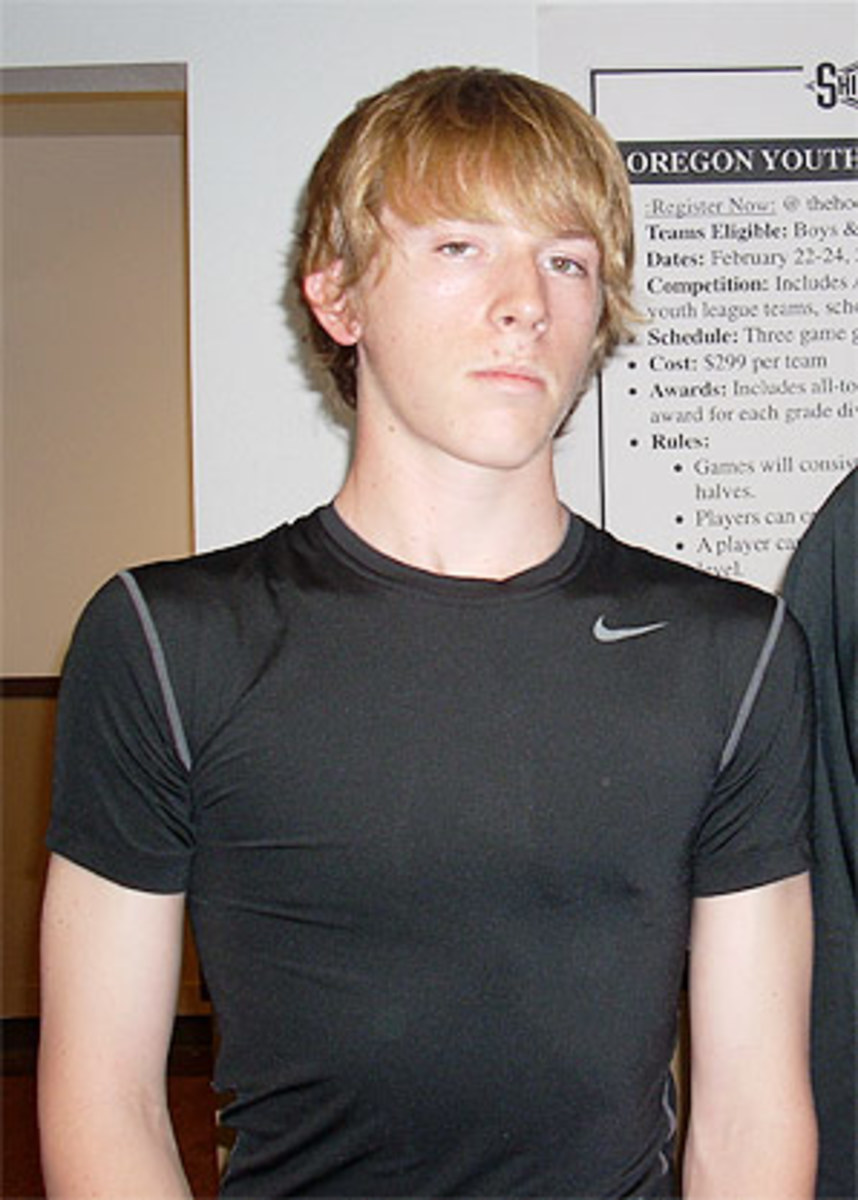

Gillispie could, however, field Avery's call two days later, after the family had returned home to Lake Sherwood, Calif., Gillispie told the proud papa that after watching Michael, a 6-foot-4 combo guard with a sweet shooting stroke, play in a pair of games with the Indiana Elite travel team, he had seen all he needed to see. Gillispie wanted Avery's son to come to Lexington. The brevity of the evaluation didn't cause the elder Avery to question Gillispie's tone, though. Neither did the fact that such a momentous occasion was taking place during a phone call instead of during a campus visit.

Avery simply couldn't believe the University of Kentucky head coach had just offered a scholarship to an eighth grader who had never set foot on campus and who still had yet to decide where he would attend high school. By now you know Michael Avery accepted that scholarship offer. When the news hit the Web shortly after Avery committed last Thursday, criticism rained on Gillispie and Avery.

The questions were pointed but predictable:

1. How could Kentucky -- college basketball royalty -- stoop to offering a scholarship to an eighth grader?

2. How could that child's parents allow him to accept a scholarship offer 40 months before he can sign a Letter of Intent?

3. Will this turn into college basketball's version of the subprime mortgage crisis with coaches (banks) trying in four or five years to excavate themselves from the wreckage of a series of bad offers (loans)?

Here are the answers:

1. Gillispie offered because he was worried someone else would beat him to the punch. In this case, "someone else" translates loosely to USC coach Tim Floyd, who accepted commitments in consecutive years from players who had yet to suit up for a high school team.

2. After three days of deliberation and discussion, Avery's parents were quite comfortable with their son's choice. Howard Avery -- who said he wasn't comfortable allowing his son to be interviewed for this story -- will explain further in a few paragraphs.

3. Possibly, depending on how well coaches can project 13- and 14-year-olds. For the time being, get used to the early offers. "These aren't aberrations," Rivals.com national recruiting analyst Jerry Meyer said Monday night, minutes before he called Greenfield, Ohio, ninth-grader Vinny Zollo for a story about Zollo's commitment to Kentucky. "It's like an arms race," Meyer said. "You've got to offer first."

Sometimes early commitments pan out. Sometimes they don't. Huntington Beach, Calif., forward Taylor King committed to UCLA prior to his freshman year at Mater Dei (Santa Ana, Calif.). Two years later, he told the Los Angeles Times, "I made my decision way too early. It was too early to know what I wanted." King eventually signed with Duke. After spending much of 2007-08 on the bench, King announced last month he would transfer to Villanova.

Meanwhile, near Chicago, guard Cully Payne still plans to sign with DePaul. Payne, a rising senior, committed to the Blue Demons prior to his freshman year in 2005, and since then he has filed occasional diaries for the Rivals site that covers DePaul.

For some, the early commitment eliminates the often stressful and chaotic recruiting process. Howard Avery hopes his son will enjoy four years of peace of mind, but from now on, his son will be known as Kentucky's Michael Avery. Opponents will try to show him up at every turn. Outside criticism will intensify.

Howard Avery got a taste of that last week, so he consulted Malume Moye, who coached Michael the past two years at Ascension Lutheran in Thousand Oaks, Calif. Moye, whose son, A.J., played at Indiana before playing professionally in Europe, reassured Howard that Michael's natural ability combined with his work ethic would make him a prime candidate to succeed.

"He was sincere in his concern," Moye said. "People had been hitting him in the head with so much negativity."

So why do some coaches feel as if they must make players choose a college before they need to choose a brand of razor?

Instead of waiting for players to mature into blue-chippers, some coaches gamble. They offer early and hope puberty, girls or grades won't keep the player from developing into a blue-chipper in high school. They also hope they don't get fired before the recruit makes it to campus. It's a risky proposition.

If the player falls short, the coach must find a way to slither out of the scholarship offer and recruit a better player without staining his reputation. Remember, coaches are the ultimate adopters. If one coach enjoys even a modicum of success after locking down middle schoolers, other coaches will start offering kids who still watch Spongebob Squarepants after practice.

That's why Floyd feels he must offer players early. Two years ago, Floyd landed a commitment from Los Angeles forward Dwayne Polee Jr. prior to Polee's freshman season. Last year, Floyd famously offered Aurora, Ill., guard Ryan Boatright, and the eighth grader quickly accepted. "What am I supposed to do?" Floyd asked in an interview with Time last year. "Should I wait until another school offers and then come in? I can't do that. Because they're going to say 'Well, you're late.'"

One man believes Floyd and Gillispie could have waited a few years and still landed Boatright and Avery. Clark Francis is the founder and publisher of Hoop ScoopOnline -- the only publication that routinely evaluates and ranks middle schoolers.

"That's where the trend is," Francis said. "You have no idea how much interest there is. Those are ($499 annual) subscriptions."

Francis doesn't believe the 5-10 Boatright will develop the game to compete in the Pac-10, and he said that while Avery is a "great kid" who "may turn out to be a very good player," Avery remains at the mercy of his DNA.

Avery will graduate with the class of 2012, but he is the same age as the members of the class of 2011. If Avery grows taller, Francis said, he could be a high Division I player. "He's very skilled," Francis said. "But at 6-4, if what you see is what you get, he's a Missouri Valley Conference player."

Howard Avery respectfully disagrees. So does Moye, who believes Michael likely will play shooting guard or small forward at the college level. While Moye isn't sure Michael can develop the quickness to guard a power-conference point guard, Moye seems certain Michael's shooting range, his quick release, his aggressiveness and his work ethic will allow him to succeed at Kentucky even if Michael -- who wears a size 15 shoe -- doesn't grow another inch.

"If he's taking a three from 22-23 feet, I feel as comfortable with him taking that shot as I would if he was standing under the bucket shooting an uncontested layup," Moye said. "He's that efficient."

So why commit now? Certainly, if Avery is as good as Gillispie and Moye think he is, he will have plenty of scholarship offers. Howard Avery, whose accounting firm bears his name, admitted he isn't much of a basketball fan except when his son is playing.

The younger Avery, however, is a basketball nut. When he finishes his two to four hours of daily training, he watches hoops. No customer of ESPN's FullCourt package got more bang for his buck than Avery. Howard said Michael watched about a dozen Kentucky games this season. Also, because he is a student of the game, Michael understands Kentucky's place in college basketball's hierarchy.

"When that kind of offer comes along, I don't care if the kid's in the third grade, the eighth grade or the 12th grade," Avery said. "You take it as a parent who is interested in getting a good education for their child."

Some may scoff and say that only a scholarship to Harvard or to a similarly prestigious institution would require such early acceptance, but remember this. Michael Avery wants to pursue a career in basketball. When it comes to basketball, Kentucky may not be Harvard at the moment, but it's at least Yale, Princeton or MIT.

"What kid who loves the game wouldn't want to play for Duke, North Carolina, Indiana, Kentucky, UCLA?" Howard Avery said. "And what parent wouldn't want to at the earliest possible time provide for the full education for their kid?"

Howard Avery's statement sounds strikingly similar to those made last year by Boatright's mother, Tanesha, who told reporters that she couldn't in good conscience tell her son to decline an offer of a $35,000-a-year education.

Parents who would prefer that their kids wait until they've at least experienced one Homecoming dance before choosing a college shouldn't worry about coaches applying undue early pressure. NCAA rules regarding contact make it somewhat easy for parents to shield their youngsters from the perils of recruiting. Even though the NCAA doesn't consider a player a "prospective student-athlete" until he enters ninth grade, coaches must abide by rules that prohibit them from initiating contact with players until the summer between their sophomore and junior years.

So while Polee has been committed to USC for almost two years, Floyd won't be allowed to call Polee or his parents until June. That's fine with the NCAA, which doesn't recognize scholarship offers until they are accompanied by a National Letter-of-Intent. Basketball players may sign a NLI no earlier than November of their senior year of high school.

"We always stress that verbal commitments are non-binding and young people can't make a formal commitment until they are old enough to sign an NLI," NCAA spokeswoman Stacey Osburn wrote in an e-mail.

Most face-to-face contact between coaches and young recruits comes at elite camps on each coach's campus. Otherwise, the player or his parent must call the coach, or the college coach must use an intermediary such as an AAU or high school coach.

Bryan (Texas) High coach John Reese, whose son, J-Mychal, is one of the top guards in the class of 2012, said his son received two scholarship offers -- from Arizona and Texas Tech -- during the summer between seventh and eighth grade, but otherwise J-Mychal has been allowed to enjoy a relatively normal early adolescence. "Nobody's beating down our doors or calling us daily," John Reese said.

Reese said he has advised J-Mychal to pare down his list of potential suitors, but the elder Reese hopes his son will hold off on a decision. Some parents of young elite prospects are curious about the trend of early offers because they don't know how it might affect their child.

Tim Peters, a Plano, Texas, tech firm CEO whose son, Zach, is a 6-8, 220-pound eighth-grade power forward, said nothing can prepare a parent for the unique challenge of negotiating a rapidly accelerating recruiting process.

"There's not a how-to book that lays it out for you," Peters said.

The problem -- critics of the early offers say -- is that unless the player has Greg Oden-type talent, the plan can change. In other cases, a coach may get fired and the new coach may cut loose all his predecessor's committed players, leaving them scrambling to find scholarships.

Howard Avery said Michael accepted Gillespie's offer with his eyes open. If Kentucky upholds its end of the bargain, Avery intends to uphold his.

"Commitment means commitment, at least in my mind," Avery said. "If facts change, that's a different story."