IndyCar driving star Castroneves living out the dreams of his father

That decorative touch foretold little Hélio's lifelong passion for driving, which would propel him to victory in 18 professional races, including the 2001 and '02 Indianapolis 500s, and -- as driver of the No. 3 car for Team Penske -- an IndyCar record seven poles in '07. A checkered flag at the Brickyard this Sunday would make him the first non-American to conquer Indy three times. "I want to win it more than anything," he says. What's more, "It's an experience I could give my dad."

Racing and music were the twin passions of the Castroneves family during Hélio Sr.'s youth, in southern Brazil in the 1960s and '70s. While his cousin Oscar was developing into an accomplished jazz guitarist who would one day help create the bossa nova sound, Hélio Sr. favored the sonorous note of exhaust -- so much so that he once traveled with his brother to the São Paulo racetrack Interlagos to turn laps in a street car. But Hélio Sr. didn't have the money to finance a driving career, so he decided to work and save toward building his own team. He sold cars in São Paulo and then industrial piping in Ribeirão Preto, an agribusiness hub about 200 miles to the northwest.

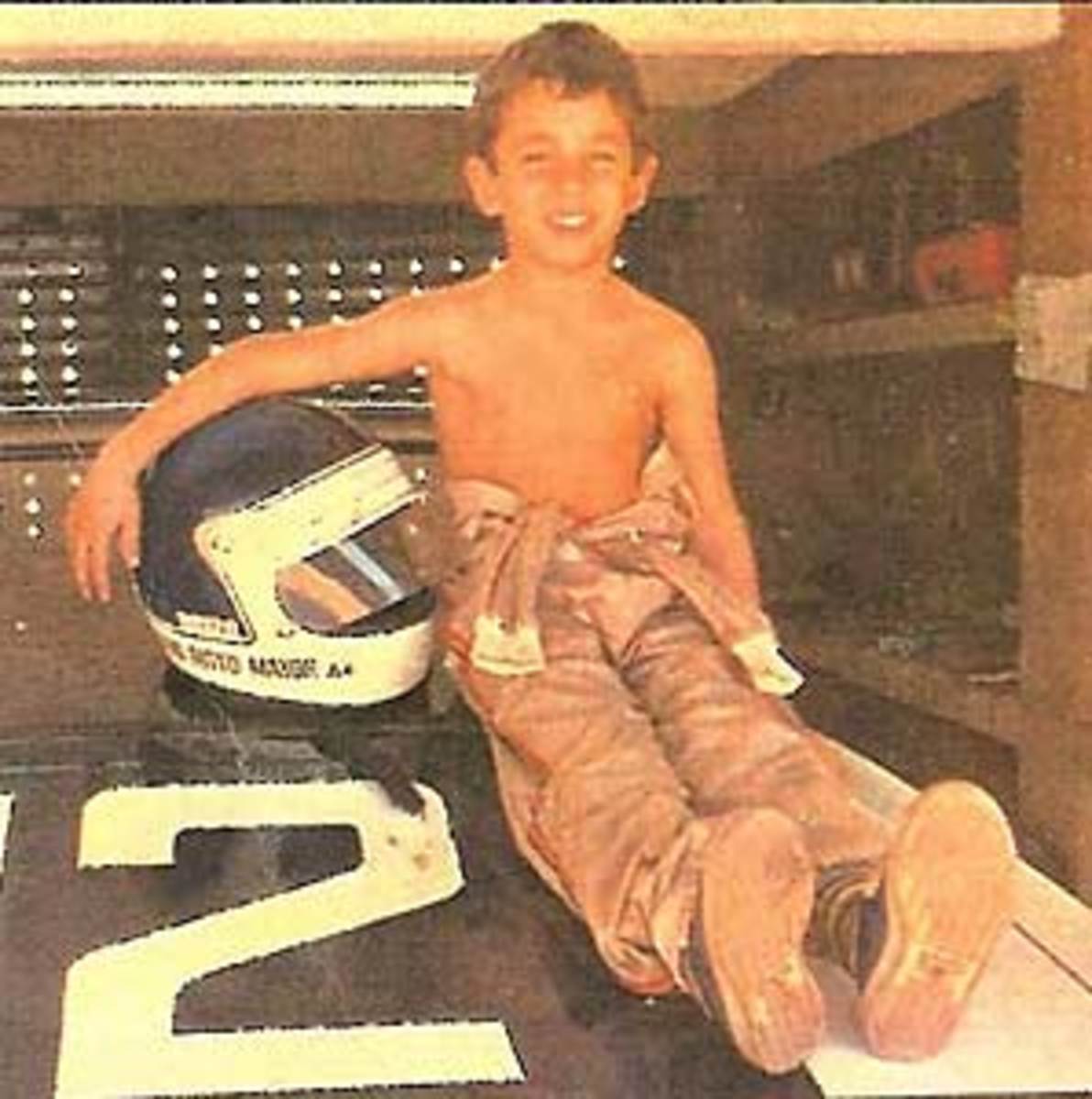

By 1980 Hélio Sr. had earned enough to launch a small stock-car team. Hélio Jr. was born in '75, and by the time he was five his dad was stashing the boy -- outfitted in a bespoke fire suit and matching helmet -- in the trunk of his car and smuggling him onto pit lane. By age 10 little Hélio was turning laps at a go-kart track in São Paulo where many of the Brazilian racers he idolized, such as the Formula One star Ayrton Senna, had honed their craft. A year later he joined a national go-kart series and won rookie of the year honors. Soon after that he told his family that he intended to pursue his father's unrealized dream.

The career choice shook his mother, Sandra, who had labored to keep her son engaged in school and to spark his interest in safer sports. ("She would sign me up for swimming, soccer or judo," Hélio recalls, "and I'd only last a week.") But Hélio Sr. was determined to give his son the backing he himself had never had. "When Hélio told me he really wanted to be a racecar driver, I felt obligated to do everything that I could to help," he says.

With teams at the Kart, Formula Vauxhall and Formula 3 formative levels all demanding $200,000 to sign his talented but unsponsored son, Hélio Sr. launched his own series of ragtag teams. In '93 he formed an F/3 team that consisted essentially of his 18-year-old son and a five-year-old, $60,000 battlewagon held together by duct tape and emblazoned with a giant white question mark -- an artful plea for sponsorship. With no money left over for a radio communication system, Hélio Sr. relayed instructions to his boy by writing on placards attached to a length of pipe that stretched from the pit to the track wall.

After the car broke in half in a disastrous early-season qualifying run, Hélio Sr. got an airline mechanic to put it back together. In his refurbished ride, Hélio stalked the points lead with three races to go -- then his beater broke down again. A rival team offered to fully sponsor him for the remainder of the season, but Hélio resisted out of loyalty to his father, but he ultimately exhorted him to "cut the umbilical cord." With his new team Hélio drove to victory in the season finale, but fell short of winning the points race.

As the demands of racing pulled Hélio away from home, he became, ironically, more dependent on his family. When he moved to England in '95 to drive for the Paul Stewart Racing in British F/3, his mother accompanied him his first three months, and his father flew in from Brazil on race weekends once a month.

When Hélio's sponsorship money dried up midseason, his father sold his business assets and private property -- including the São Paulo apartment where Hélio's sister, Kati, lived as she pursued an MBA and her own dream career as a ballerina. She had no qualms about having to find a roommate and solicit sponsorship money for her little brother from her marketing professors. "We always thought the four of us were going to make it somehow," says Kati, who is now Hélio's business manager. And even if Hélio had not succeeded as a driver, his father says, "Our efforts would have never been in vain, because he is my son."

That trying season in England paled in comparison to Hélio's first frustrating years in the U.S.-based Indy Lites series, after Tasman Motorsports signed him in '96. He struggled through a spate of crashes and race disqualifications that made him few friends inside the team garage. It didn't help that he was slow to master English (his speech was confined mostly to racing argot like understeer and oversteer). By midseason of '96 he was so frustrated that he briefly sought the help of a sports psychologist. In a tearful phone call he told his father, "My racing career is over." Hélio Sr. urged his son to keep fighting.

The following year Hélio rose to the Champ Car series, where he spent two seasons chasing his first victory. But this time, rather than sulk, he decided to learn from his mistakes and carefully analyze his poor results. When he finally broke through, achieving his first major open-wheel victory in Detroit in '00, Hélio bounded from his cockpit and scaled the trackside fence at The Raceway at Belle Isle in what would become his signature victory celebration and earn him the nickname Spider-Man. "Racing is full of more frustrating times than happy ones," he says, "so when I achieve happiness, I really enjoy it." Eleven months later he climbed a fence again at the Brickyard after taking the first of his two checkered flags at the Indianapolis 500.

* * *

Castroneves was two hours away from the start of last year's Indy 500 when a friend, U.S. speedskater Apolo Anton Ohno, approached him about competing in the hit TV series Dancing with the Stars. Ohno's '07 win on the ballroom dancing show, in which celebrities and sports figures compete for call-in votes, had made him exponentially more famous than the two Olympic gold medals he had won in Salt Lake City in '02 and Turin in '06.

Eager for similarly mainstream stardom, Castroneves signed with Dancing and moved to Los Angeles in the racing offseason to learn his steps and tape the show. He practiced for six to 10 hours a day with Ohno's former partner, 19-year-old professional dancer and country music artist Julianne Hough. At first they struggled to develop a chemistry. "When I'm driving, I only have to depend on myself," Hélio says, "and it was hard to give power over to Julianne."

By his own admission Castroneves is still not the most skilled hoofer. He approaches each routine as he would a circuit course, following an imaginary footpath from start to finish instead of heeding the musical tempo. In the end it was his dimpled smile and natural charisma that endeared him to the U.S. public. "My grandmother absolutely adores him," says fellow driver Danica Patrick.

Patrick herself was one of Castroneves' many enthusiastic backers in the racing community. To drum up support for him in Indianapolis for his Dancing bid, IndyCar funded taped endorsements from Colts coach Tony Dungy and Indiana Pacers star Jermaine O'Neal to be shown on TV, and series employees placed VOTE FOR HELIO signs on lawns. NASCAR's Mark Martin called Castroneves in the middle of a pre-race briefing to promise votes from him and his wife.

That campaign helped propel Castroneves to victory on the show and make him a national celebrity. Since his dancing triumph he has appeared on Oprah and analyzes the current season of Dancing with the Stars for Entertainment Tonight. Off-camera he makes cameos with a crowd that includes Dancing alums Wayne Newton and Floyd Mayweather, Jr., an honorary starter at this year's 500.

But the true measure of Castroneves's household fame became clear when his love life became grist for the supermarket tabloid mill. News of the dissolution of his engagement to Cuban jewelry designer Ali Vásquez broke on the heels of his Dancing victory, which he punctuated by kissing Hough on the lips in a closing number that drew inspiration from the swing dance scene between Jim Carrey and Cameron Diaz in The Mask. (Even the banana yellow zoot suit and matching wide-brim gangster hat that Castroneves wore for the routine borrowed from the '94 flick.)

The finishing move gave rise to rumors that Castroneves had jilted Vásquez for his dancing partner -- who called off her own engagement after the show. In the tried and true manner of celebrities rumored to be dating, however, Castroneves and Hough insist they're just good friends.

Still, there's no denying the fact that Castroneves has also emerged as a crossover star in his own sport in his ninth season of North American open-wheel racing. Seeking to recover the cachet it long ago ceded to NASCAR, open-wheel began an earnest resurgence in February when the sport's two rival series -- Champ Car (where he got his major start a decade ago) and IndyCar (his home for the last seven years) -- reunited after a 12-year rift.

So far, new challenges that have included an influx of new drivers and the addition of four races haven't diverted Hélio from his lifelong goal of winning his first ever points championship. He has finished no lower than fourth in his first four races this season and leads the points standings heading into Indy, where another of his challenges will be fulfilling the lofty expectations of his legion of Dancing fans. "My initial goal in doing the show was to reach fans who had no idea about racing," says Hélio, who started on the pole in '07 and finished third. "Now it's up to me to deliver a great experience."

Whether or not he climbs the fence at the Brickyard a third time, he has already soared immeasurably in the eyes of his most ardent supporter. "I couldn't realize my dream of becoming a racecar driver," says Hélio Sr., "but seeing my son succeed was even better."