Thigpen: 'I'm happy for him'

Perhaps as early as this weekend, Francisco Rodriguez of the Los Angeles Angels will snuff out yet another team's hopes for victory, save another win for the AL West champs and in the process, erase a name from the record book that would already have been forgotten by most fans had it not endured atop a significant, albeit misunderstood, statistical category for nearly two decades.

And when that happens, and the name "Bobby Thigpen" can no longer be linked with the words "baseball's single-season saves leader", the man who has just become a historical footnote will tip his cap to his successor, think again of his own journey to that record, and recede into the cluttered wilderness of baseball's forgotten names.

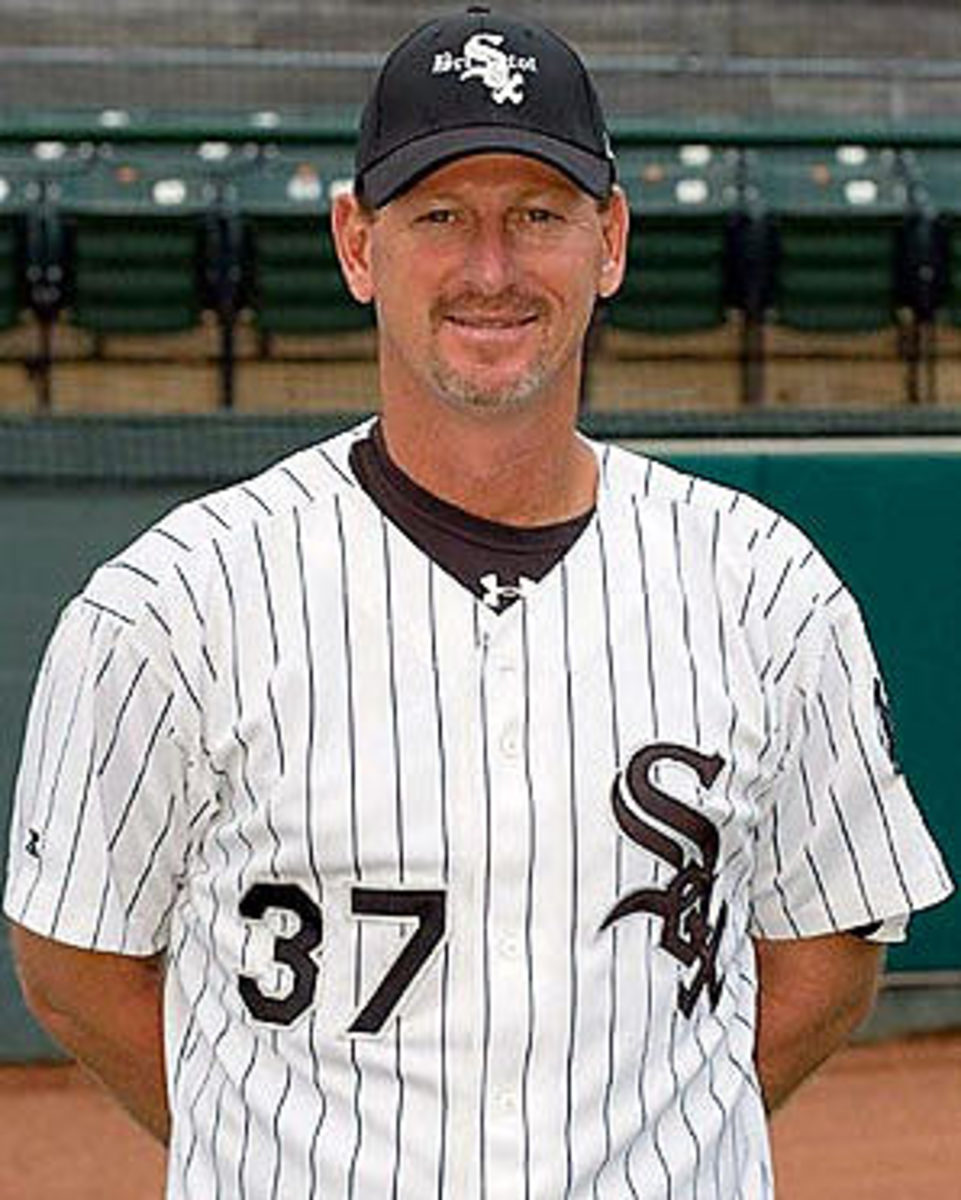

Truth be told, it won't take long for Thigpen to be forgotten by all but a small group of fans. Even during and after his record-breaking 57-save season of 1990, Thigpen was never a star on the magnitude of K-Rod, and he has remained largely out of view throughout K-Rod's pursuit of his record, just as he has since retiring from baseball in 1996. In March 2007, after a decade of coaching high school baseball, Thigpen finally got into pro ball as the manager of the Bristol White Sox, Chicago's Rookie League team in Virginia. There he guided men, kids really, for whom Bristol would barely register in their memory bank of baseball memories as they moved on to bigger and better things, and others for whom Bristol would be their one chance to say they played professional baseball.

But if there's one trait those kids had in common, it was this: None of them knew their manager held a significant major league record. "Absolutely no idea," says Thigpen, 45, with a laugh during a recent phone call from his home in Florida. His season in Bristol was already over by late August, and he had returned to the St. Petersburg area to be with his family and watch K-Rod's assault on his record continue. "They were barely born when I broke it. But this year kids came into the clubhouse and said 'I saw you on TV last night'. Even the Latin kids that don't speak much English."

It has been Thigpen's fate to hold a record that is paradoxically famous and yet not completely respected. Hit a home run and everyone knows what that means and appreciates its impact. Get a save and very often the response is a shrug and a comment like, "Anyone can do that."

But if anyone can -- and certainly the number of those calling themselves closers since Thigpen set the record in 1990 doesn't do anything to add to the record's mystique -- then why hasn't anyone been able to accrue enough saves in one season over the last 18 years to knock Thigpen from the record books? As the save has become more common, the closer's role more narrowly defined, and its practitioners more trained for their unique task, it seems Thigpen's record should have become as much a relic of the early 1990s as MC Hammer.

Instead it endured, withstanding attacks by Cy Young winners and future Hall of Famers alike. Until K-Rod, no pitcher had topped 55 saves since Thigpen's 57. "I thought if I got to 60 it would never be broken," says Thigpen. "If he gets over 60 he could actually keep it out of reach."

Unlike K-Rod or most of today's star closers who are groomed for their one-inning stint, Thigpen didn't set out to be a closer. He didn't even set out to be a pitcher. An outfielder at Mississippi State, he moved full-time to pitching after joining the White Sox organization, and it wasn't until he reached the major leagues in 1986 that he became a reliever. In fact, says Thigpen, "I had no clue why I was being called up because I wasn't doing that well."

The next year Thigpen recorded 16 saves, and by 1988 he was the anchor of the White Sox's bullpen, notching 34 saves, a total he would match in 1989.

A lockout delayed the start of spring training in 1990 and Thigpen gave no indication he was headed for a historic season. "I always struggle in spring and I had a typically unsatisfactory spring that year," he said. "But when we opened up, I got a save on Opening Day and it kind of snowballed from there."

By the All-Star break that July, Thigpen had a first-half record 27 saves but still wasn't recognized as his league's preeminent closer. Even though the All-Star Game was in Chicago, AL manager Tony La Russa used Thigpen (in his only All-Star appearance) in the seventh inning, choosing his own closer, future Hall of Famer Dennis Eckersley, to nail down the AL's 2-0 win.

As the season resumed and Thigpen's saves total piled up, there was little attention paid to the existing record of 46 in a season, set just four years earlier by Dave Righetti of the Yankees. Part of that was due to a lack of historical significance and part to Thigpen's underwhelming career and standing in the game. With a modest 6'3" frame, Thigpen didn't strike fear in opposing batters the way hulking closers such as Lee Smith, Tom Henke or Goose Gossage did, and with only a single All-Star Game appearance and no postseason experience, Thigpen was a relative unknown in the sporting world.

Yet he was one of the biggest reasons why the overachieving White Sox managed to hang in the AL West race. The Sox seemed to always be good enough to give Thigpen a lead to work with in the ninth inning, and rarely good enough to blow a team out. As a result, Thigpen had a major-league record 65 save opportunities in 1990, 22 more than he did the year before and 26 more than he would have in '91.

"If anything, I was underused," says Thigpen, who pitched 88.2 innings that season. "I got better the more I played." When detractors pointed out that he never again reached the heights of his 1990 season, Thigpen had a ready answer. "How can I get 45 or 50 saves if I only have 37 opportunities?"

Thigpen entered September with 45 saves, one behind Righetti. On Sept. 3 he took the mound at Comiskey Park against the Royals, trying to protect a 4-2 lead. With one on and one out, Thigpen got future Hall of Famer George Brett to ground into a game-ending double play. There was no ceremony, no fanfare. The White Sox were still in a pennant race (they would finish second in the AL West to the A's) and Thigpen's season was far from over.

But the magnitude of the moment was not lost on the man of the hour. "I couldn't talk, and needed to go compose myself," he says. "There's so much emphasis put on that one inning and if you don't do the job you feel the weight of it and you feel you let the team down."

Thigpen took the ball from the final out and gave it to his mother. In fact, he gave away most of the balls from his record-breaking season. But there was one memento he wanted: an autographed bat from Brett, and he got it during the White Sox' first trip to Kansas City the next season.

By then, Thigpen was already on the downside of his career. He saved 30 games in 1991 and 22 in '92, when he lost his closer's job to Roberto Hernandez and Scott Radinsky (the trio each saved at least a dozen games).

By 1993 Thigpen was gone from Chicago and he pitched his last major league game in '94, the year he turned 31. He retired two years later and since then has watched a steady progression of baseball's best relief pitchers attack his record, only to watch it endure one more year.

With his milestone finally destined for extinction, Thigpen has no regrets that his tenuous grip on his place in history will be, for all intents and purposes, lost forever. "Obviously I would have liked to have kept the record," says Thigpen, who says he has no plans to go to Los Angeles to watch K-Rod break his record but does plan on sending him a congratulatory note. "I don't want to take anything away from K-Rod. He's the one having the great year and there are only a handful of guys that know the type of year he's having and what he has to do to get those numbers. I look for him to break it and add to it. I'm happy for him."