Like in politics, many have paved the way for change in sports

Buck O'Neil believed in this America. He talked about it all the time, this America, the America they show on television now at 11 o'clock at night, 10 o'clock in the prairie, 9 o'clock in the mountains, 8 o'clock on the West Coast, where they always show 60 Minutes at its regularly scheduled time.

On television, a huge crowd crams together at Grant Park in Chicago -- young and old, men and women, famous and anonymous, black and white and every shade -- and they cheer for Barack Obama, seconds ago projected to be the next President of the United States. Only, Barack Obama isn't here yet. So, really, they cheer for America.

And I wish ol' Buck could have lived to see this moment, because this is a picture of the America he always talked about, day after day, night after night, at every Elks Lodge, at every VFW hall, at every Optimist Club, Kiwanis Club, Shrine Club, Rotary Club, on every radio talk show, at every Little League dinner. Buck O'Neil was born in 1911. He was the grandson of a slave. He was the son of a man who had to skip town after fighting off a white police deputy who insulted his wife. Buck cried when told he could not go to Sarasota High because the school was for white kids only.

"Don't cry," his grandmother told him. "Someday, everyone will get to go there. I may not live to see it. But you will."

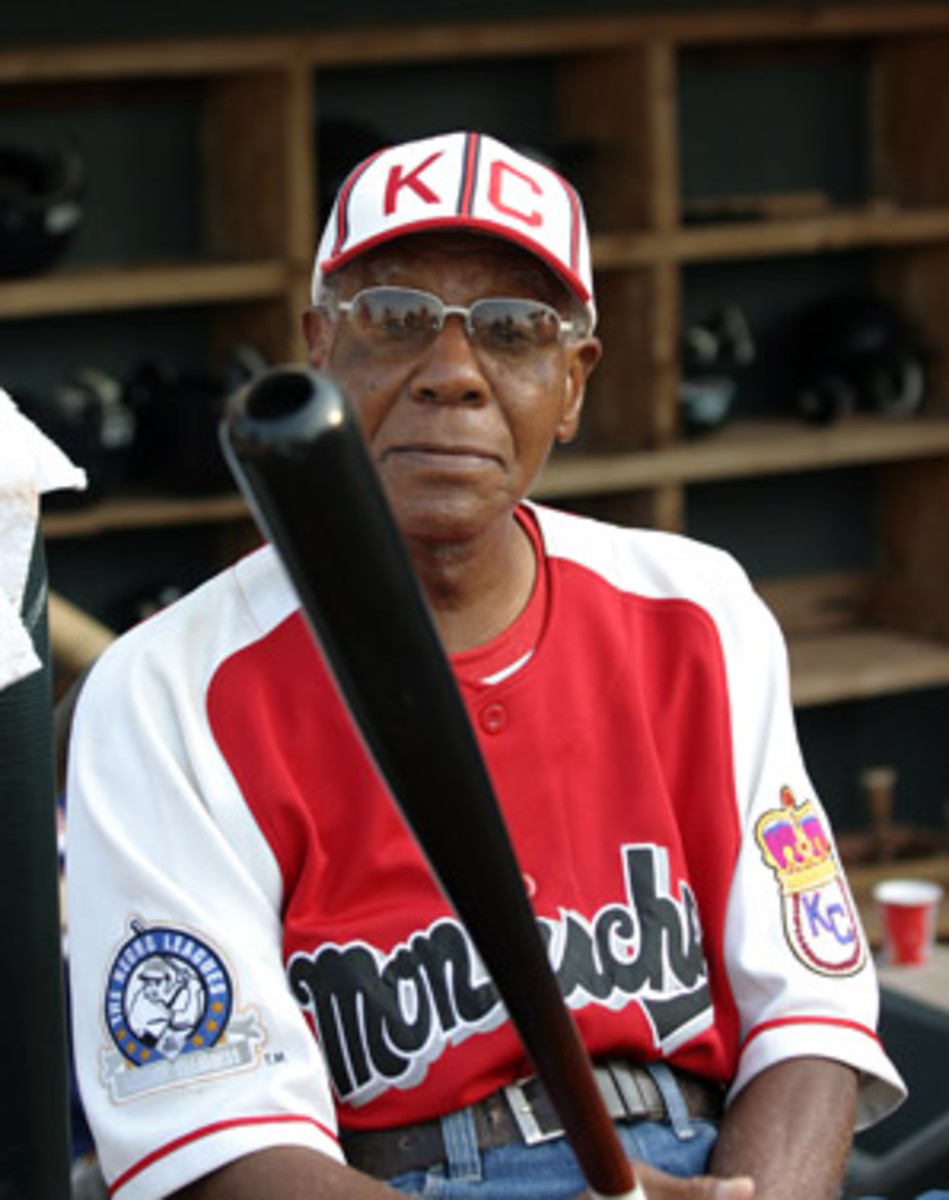

He did. He went back to Sarasota late in his life. That was after he played baseball in the Negro leagues, after he served in the Navy during World War II, after he managed the Kansas City Monarchs with greats like Satchel Paige and Ernie Banks and Elston Howard, after he coached the Chicago Cubs, after he had criss-crossed the country scouting baseball and talking baseball. After all that, Buck went back and got his high school diploma from Sarasota High.

Buck lived to see so many things, so many firsts. It's funny: Watching Election Day coverage is so much like watching a sporting event, so much like watching the pregame NFL shows. You have all these experts sitting behind desks with fancy graphics on the screen below and they argue and pontificate about what will happen or why something happened or why something didn't happen or what it all means. The only differences seem to be that Election Day folks get cooler gadgets and touch screens, while NFL pregame shows don't get as many partisan analysts.*

*You have to wonder when sports coverage will go political and start hiring boosters and zealots to give their opinions. Seems like there will come a day -- and soon -- when the pregame shows will get a really big, almost delusional Cowboys fan and a lifelong, violently loyal Eagles fan to give us some real analysis before a Dallas-Philadelphia game. Maybe it's just me, but I don't see how this is much different from having Bill Bennett and Paul Begala breaking down the election for us.

Tuesday's election, though, felt even more like a sporting event because they kept using the word "first." Well, sure, Barack Obama will become the first African-American president. If you think about it, that's really a sports thing -- in athletics we keep a close tab on the firsts. Sports celebrate the trailblazers and the pioneers. I'm not sure many people could name the first African-American millionaire or the first woman to graduate from Harvard or the first minority* to serve in the Senate or the first to write a best-selling book.

*One of the great election moments came when someone on one of the netwoks said, with amazement in his voice, that "Forty percent of America are minority voters." So true. Forty-eight percent makes up a minority too. Also thirty-six percent.

But everyone knows Jackie Robinson was the man to break the color barrier in baseball in 1947. And, after Robinson, every step of progress has been painstakingly marked in sports. Althea Gibson became the first black woman to win Wimbledon. Bill Russell became the first black coach of an NBA team. Arthur Ashe became the first black man to win Wimbledon. Frank Robinson became the first black baseball manager. Art Shell became the first black coach in the NFL (or the first since Fritz Pollard, who coached the Akron Pros in 1921). Bob Watson became the first black baseball general manager. Tony Dungy became the first black coach to win the Super Bowl. Tiger Woods, of course, changed everything about golf.

Somewhere in the middle of all that, Buck O'Neil became the first black coach in Major League Baseball -- that was in Chicago, for the Cubs, in 1962. He was, in too many ways, a token hire; he was as qualified as anyone to be a big league manager, much less a coach, but realistically they brought him in mostly to serve as a bridge to Lou Brock and Ernie Banks and Billy Williams and the other African-American players. The Cubs never let O'Neil on the field, not even to coach first or third base. "I would have liked to do that, even if it was for only one game," Buck said. "But it just wasn't time yet."

He said that with no bitterness -- Buck just seemed to have no bitterness in him. He believed in the passing of time and in the slow but steady rhythms of change. He had seen so much of it in his life. One of the first paying gigs he ever got playing baseball was with the Zulu Cannibal Giants, a minstrel show of a baseball team in which the black players wore grass skirts and war paint on their faces and swung giant clubs in place of baseball bats. "So degrading," Buck said on those rare occasions when you could get him to talk about it.

One of the last things he did before he died was to speak at the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, N.Y. They now have a statue of him there, unveiled just this summer.

And along the way he saw so many little changes, small moments mostly, a young boy in North Dakota who promised to never call anyone the "N-word" again, a white woman in Kansas who held his hand in church, a gas station owner in Oklahoma who desegregated his Whites Only bathroom because he could not afford to lose the business, a white high school baseball player in Alabama who would knock his hat off as he ran so that he could look a little bit like Willie Mays.

Buck loved those small moments even more than the big ones, the breakthroughs, like Tiger winning the Masters or Nolan Richardson coaching Arkansas with its 40 minutes of Hell to the national title or even Buck himself shaking hands with presidents. I think I know how proud he would have felt Tuesday night. But I'm not sure he would have felt any prouder than he felt when a little boy in Seattle said that his favorite players were Sammy Sosa, Ken Griffey and Greg Maddux. That boy could have been white or black. It didn't matter.

One of the great thrills of my life is that for about 18 months before Buck died in October 2006 -- he was almost 95 years old -- I traveled the country with him for a book I wrote, The Soul of Baseball. Again and again, I saw him light up with joy as he saw what America had become. "Yeah, we have a way to go," he would say to those people who sounded discouraged. "We'll get there, man. I wish you could see what I've seen."

He could not get enough. He spoke in classrooms and chatted with people at ballgames and went up to complete strangers in restaurants and at airports, and he believed in this America. It isn't perfect, of course, nothing close to perfect, and there's always a lot to do. Buck said that plenty. But, more, much more, he said: "Look how far we've come. Look how much we've grown. Look how much closer we are."

"How old are you?" he asked me once along the road. I told him.

"Just think," he said. "You will live long enough to see a black president."