Tragedy at sea brings back chilling memories of Anthony Latham

That's the tragedy of it all. Not the drowning, not the funeral and not even the horrible memories of that fruitless search for life off the Gulf of Mexico in the fall of 1983.

No, the most haunting part, hands down, is that Anthony Latham should be here. He would be 47 years old, that much we know. But the rest, well, the rest is a painful game of What If? Perhaps Tony Latham, having completed a lengthy major league baseball career with the Boston Red Sox, would be managing a Triple-A team somewhere in the Midwest. Perhaps having fizzled out after a few mediocre minor league seasons with the Boston Red Sox, he would have completed his aerospace degree from the University of Virginia and gone on to work for NASA. Perhaps he would be contentedly single. Perhaps, somewhere out there, a woman exists who -- had fate called for calmer water or different decisions -- would be Mrs. Tony Latham right now. Perhaps they would have raised two children, or three, or four.

"I think about that," said Vickie Presley, a middle school principal and one of Latham's four older sisters. "Who would my brother be today? What did life hold for him?"

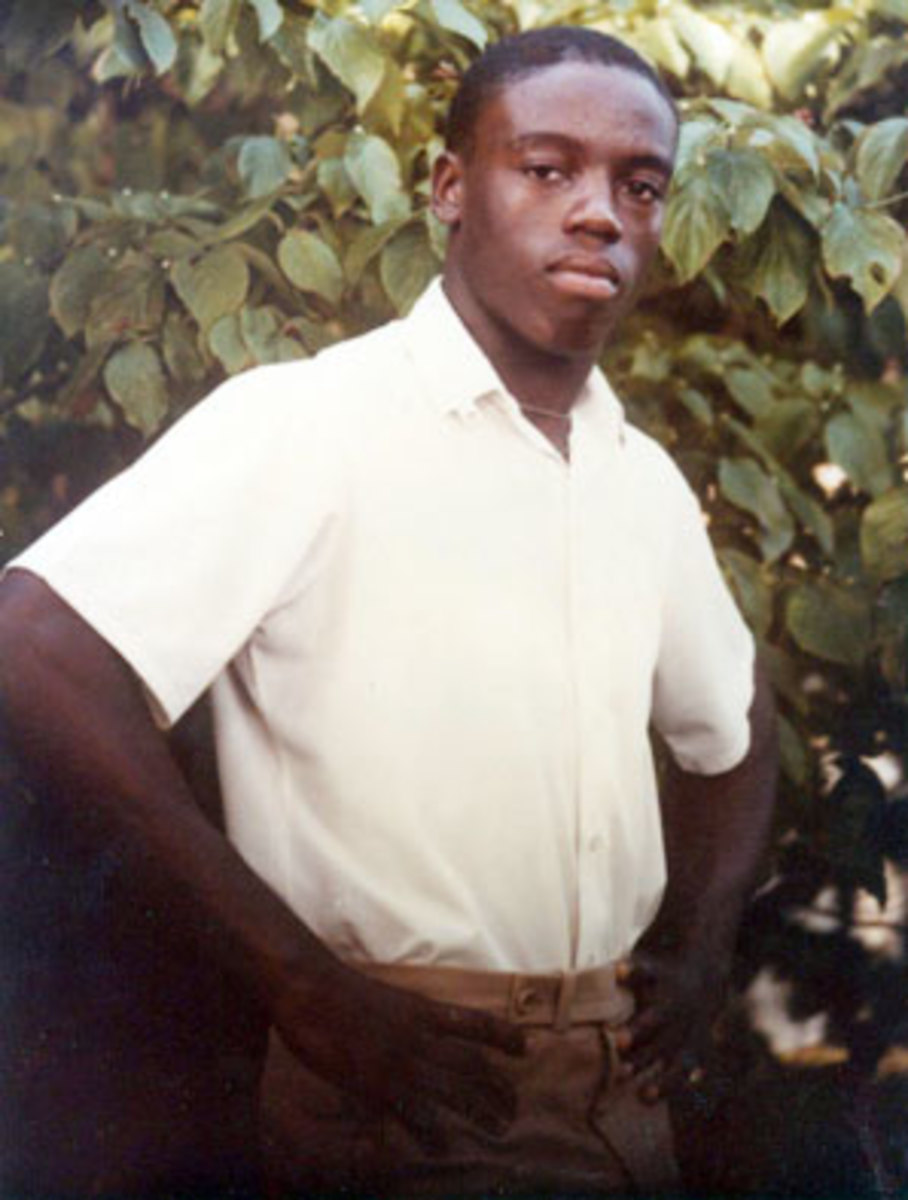

Presley pauses, then stops talking altogether. The questions, tragically, answer themselves. Tony Latham has been dead for 25 years. His fate is sealed. "He was a beautiful boy," said Shirley Latham, his mother. "Just beautiful ..."

Over the past few days, as news outlets relay the saga of the four athletes recently lost in the waters off of Clearwater, Fla., a handful of people have found themselves sent back through time, to a nightmare eerily similar in geography and circumstance to the one of present day.

On Feb. 28, 2009, two NFL veterans, Marquis Cooper and Corey Smith, along with former University of South Florida players Will Bleakley and Nick Schuyler, were anchored 38 miles offshore, fishing, when rough waters capsized their 21-foot boat. On Oct. 30, 1983, three Red Sox minor leaguers, Latham, John Mitchell and Scott Skripko, along with Mark Zastrowmy, a native Floridian and owner of the boat, were roughly 10 miles offshore, fishing, when rough waters capsized their 17-foot boat. In 2009 three of the men were apparently lost, while the fourth, Schuyler, survived by holding on to the side of the boat for more than 30 hours. In 1983 two of the men, Latham and Zastrowmy, were lost. Skripko, an outfielder, survived by holding on to a cooler for 20 hours, while Mitchell, a pitcher, survived by holding on to a bucket for 22 hours. In 2009 the pain experienced by the loved ones of the recently deceased is as raw and piercing as a knife wound to the gut. In 2009 the pain experienced by the loved ones of the long-ago deceased is as raw and piercing as a knife wound to the gut.

"It doesn't go away," said Shirley Latham. "You wish it would, but it doesn't. It just doesn't."

Especially now. When she first heard the news of the recent accident, Presley was frozen in her tracks. Though the framed photograph of Anthony that rests atop the piano in her Port Orange, Fla., home reminds Presley of her baby brother on a near-daily basis, the words emanating from a TV newscaster's lips -- LOST AT SEA; ATHLETES; FISHING TRIP; GULF OF MEXICO -- well, they were devastating. "It was like re-living the entire incident," she said. "Like having it happen all over again."

* * *

On the morning of Oct. 30, 1983, Tony Latham, John Mitchell and Scott Skripko, all members of the Class A Winston-Salem Red Sox, all stationed in Port Charlotte, Fla., for a couple of months of Instructional League baseball, decided to use a rare off day for a brief fishing excursion. Skripko, a recent third-round draft pick out of Middle Georgia College, knew a man, Zastrowmy, who owned a boat and would happily escort them out into the water. "That day the waves were choppy, and the boat was only a 17-footer," said Mitchell. "We weren't supposed to be out there, especially without life jackets. But it was our one day off, and we really wanted to fish."

Mitchell, a Nashville native and one of the Red Sox's top pitching prospects, was comfortable in the water, as were Skripko and Zastrowmy. Latham, however, was not. In high school and college, teammates had jokingly nicknamed him "Lakeside" for his inability to swim. A gregarious young man with high cheekbones and an infectious laugh, he never took the ribbing to heart.

Born and raised in the lower-middle class town of Robersonville, N.C., Latham was a clean-living kid who played the saxophone and excelled in every imaginable sport -- tennis in the fall, basketball in the winter, baseball in the spring. "Oh, did he love baseball," said Presley. "That was his first passion."

A natural outfielder, the speedy Latham earned an athletic scholarship to the University of Virginia, where he was the only African-American on a roster of 33 players. The year was 1981. There was still a good amount of racial hostility in the south. Many Virginia players had never befriended a black man before.

"Forget it -- he fit in perfectly," said George Priftis, the team's star second baseman. "People were naturally attracted to Tony, because he just had this infectious way about him. He was an excellent baseball player -- he could run, he hit for power and he had a powerful arm -- but that had nothing to do with why we liked him. He was just a great human being. Someone who always had a smile on his face."

With a laugh, Priftis recalls the time the Cavaliers played a fall road game at James Madison, and Latham forgot to bring his bat. "We had this weighted 54-ounce bat, so Tony dragged it up to the plate," he said. "We were all cracking up, and then Tony hit a single with it."

Latham was selected by Boston in the fourth round of the 1983 draft, and hit .275 with two home runs and nine RBIs in 40 games at Winston-Salem. Considering he had gone straight from college to the minors to the instructional league, it had been a long year of baseball, and the fishing trip seemed like an ideal chance to relax and take his mind off the game.

"So we go out there, and before too long the boat starts holding water," said Mitchell. "It was a slow leak, and [Zastrowmy] told us we had to take the boat in. I don't think anyone was overly alarmed, because the water wasn't coming in too fast, and we figured we had time."

The ballplayers were so casual, in fact, that the man at the wheel was the inexperienced, sea-fearing Latham. The boat was rolling along, heading closer to shore, when a wind blew Zastrowmy's baseball cap into the waves. "Do you want me to stop so we can get that?" Latham asked.

"Sure," said Zastrowmy. "It'll only take a minute."

Not knowing how to deftly handle a boat in choppy waters (or, for that matter, a boat in any waters), Latham shifted to full throttle, crossing his own wake in the process. Boom! Waves slammed over the side. Latham slowed down, and the water came even higher, faster, harder. "Maybe we had too much weight up front," said Mitchell, "but the boat nosedived. The thing went straight down. There was no delay -- just down to the bottom, like a rock."

The four men plunged into the water, then bobbed to the surface. "I can't swim! I can't swim!" Latham screamed. Mitchell grabbed a nearby life preserver and tried throwing it to his teammate, but the wind blew it away. He then made his way to Latham, grabbed his arm but was unable to keep him afloat. Mitchell saw Skripko and yelled, "He's got to have something, he's going to drown!" Skripko threw a small cooler toward Mitchell, who placed it below Latham's chin to use as a flotation device. "Then I let go of Tony and turned my head," Mitchell said. "When I looked back, he was gone."

* * *

For the ensuing 22 -- yes, twenty-two -- hours, Mitchell lived by grasping a five-gallon minnow bucket. "I held it upside down to trap in the air," he said. "I kept it under my chin throughout the night, just trying to kick my feet and stay awake."

Mitchell thought he was destined to die. Knew he was destined to die. One hour turned into three hours. Three hours turned into 10 hours. Ten hours turned into 17 hours. At first, he was able to keep in contact with Skripko and Zastrowmy, both of whom were holding on to coolers. But over the course of the night, when the sky turns pitch black and the imagination does cruel things, the three were separated. "I actually fell asleep a few times, with my head on the bucket," said Mitchell. "But then a wave would come ..."

What is it like, being alone in the ocean, left to die? Mitchell does not have the words. Scary, for sure. But more than that. His mind wandered. To his family. To his friends. To Tony Latham. Was this how it was supposed to be? Mitchell was 23 years old, with a long baseball career ahead of him; a long life ahead of him. "I never gave up," he said. "I couldn't."

At one point, Mitchell saw a boat in the distance. He screamed for help. Screamed again and again. Nothing. "He didn't hear me," he said. "Help wasn't coming."

Finally, at 12:30 Monday morning -- nearly a full day after the boat had capsized -- Skripko, bobbing five miles away from Mitchell, spotted fishermen 150 yards in the distance and was able to attract their attention by whistling. Two hours later Mitchell was picked up, too. He was suffering from hypothermia but otherwise OK. Like Latham, Zastrowmy had drowned. He was 35 years old.

"I don't think about that experience all the time anymore," Mitchell said. "But it will never leave me. Never."

* * *

Much like the recent tragedy, when Schuyler's rescue gave optimism to the families of the three other victims, Tony Latham's parents and sisters learned of the disaster and drove straight to Sarasota, where they hoped good news awaited.

"We prayed for the best," said Shirley Latham. "We prayed and prayed. But in my heart, I knew. I knew from the first time they called to tell me what happened, when I just dropped the phone and started crying. That was my baby. My baby boy."

As the days passed and Tony Latham remained lost, hope turned to dread, and dread turned to crushing acceptance. Finally, after waiting for more than a week, Shirley, her husband Josephus (who died in 2003), and their daughters decided to return to Robersonville.

"That's when they called me and said they had some good news and some bad news," said Presley. "The good news was they had found Anthony. The bad news was that he was dead."

The family went to a dock, where they were shown a black bag containing the body of Anthony Latham. Josephus looked at his son's face, an image that surely remained with him until the day he passed. "But the rest of us didn't want to see him, so we chose not to," said Presley. "We wanted to remember him the way we last saw him."

As the days turned into months, and the months turned into years, the pain gradually dissipated. Horrible memories are replaced by funny stories; the mental images of Anthony Latham dying are locked away, replaced by the mental images of Anthony Latham living. When people ask about her brother, Vickie likes to share a poem he once wrote, titled, I Am.

As an athlete, I am quite talented.I can participate and accomplish almost any feat in any sport.As a student, I am quite regular.I enter each course with an open mind and with the thoughts of trying to comprehend the course as quickly as possible. The sooner I do, the better my grades.As an everyday person, I view all problems with an open mind. When problems, whether personal or not personal arrive, I try to solve them with the most reasonable and logical answer. At times, I find myself to be quite impassive in my reasoning.I am not an egotistical person.

One of Shirley's grandsons is named Anthony Williams. He took lessons on his late uncle's saxophone; followed his athletic path and played second base for Mount Olive College in North Carolina before recently graduating. "I have a 19-year-old daughter named Tai," said Presley. "She's a sophomore at Bethune-Cookman, and I always think how proud her uncle would be of her."

Skripko, who declined an interview request for this story, went on to play five seasons in the minor leagues, compiling an 18-19 record but never rising above Class AA. He lives in New Jersey. "The last time I saw him was years ago in Atlantic City," Mitchell said. "The accident never came up. I don't think it's something we want to talk about."

Mitchell, Boston's seventh-round pick in 1983, spent parts of five seasons in the major leagues, earning a World Series ring with the 1986 New York Mets by appearing in four games, and winning a career-high six games with the 1990 Baltimore Orioles. He now lives in Nashville, where he works for a company that makes municipal castings. He is married with three children.

His 13-year-old son is named Johnny Mitchell.

Johnny Latham Mitchell.