A-Rod in Texas: Mr. 252

This article appears in the May 11, 2009 issue of Sports Illustrated magazine.

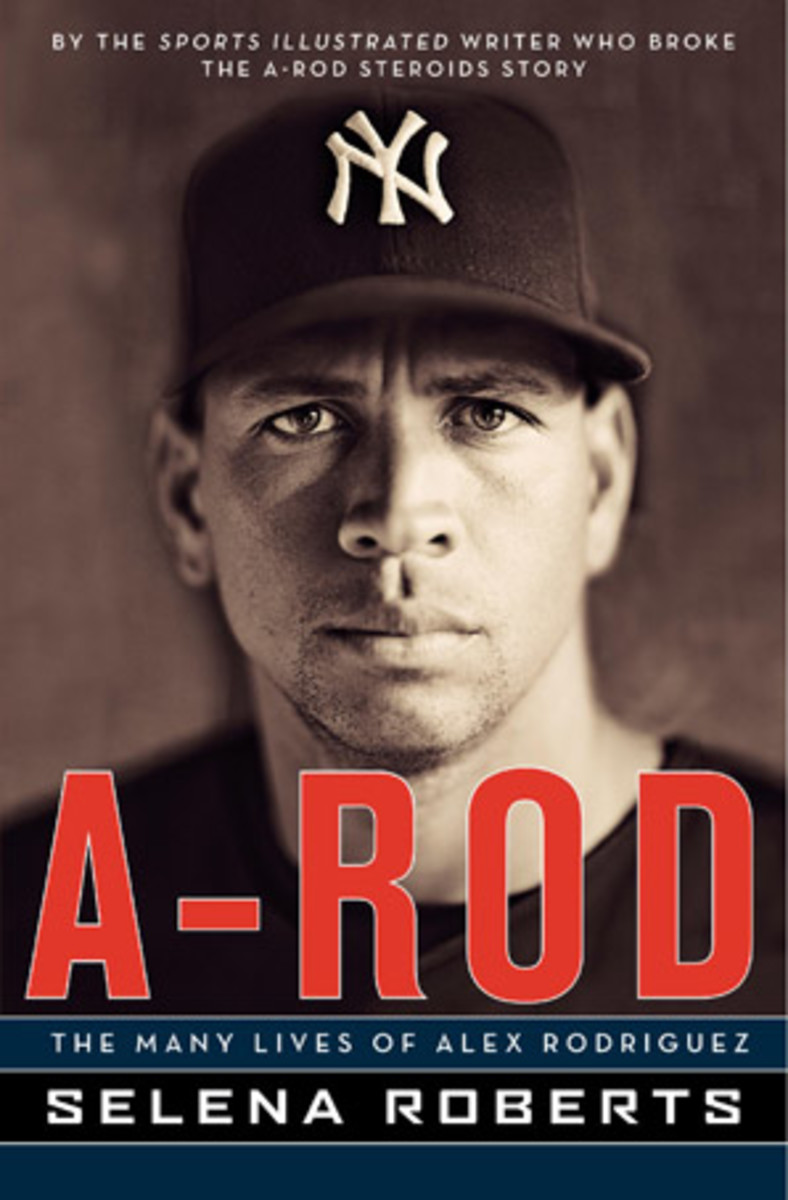

From the book A-Rod: The Many Lives of Alex Rodriguezby Selena Roberts (HarperCollins Publishers). Copyright (c) 2009 by Selena Roberts.

It was a splendid April 1 in San Juan, sunny and warm. Major League Baseball had come to Puerto Rico for Opening Day of the 2001 season, hoping to expand its Latino fan base. One day earlier Texas Rangers owner Tom Hicks stood in his soaked swimsuit at a resort hotel and declared his team a lock to win the American League West. ESPN was onsite to broadcast the debut of Alex Rodriguez with his new club.

The atmosphere was electric. Crowds formed on the roads leading to the teams' hotel, hoping to get a glimpse of the players. As the buses of the Rangers and the Toronto Blue Jays were escorted by police through the city, pedestrians clapped and cheered. "You felt like the President was coming," recalls Alex Gonzalez, who had played youth ball with Rodriguez in Miami and would start at shortstop for Toronto that day. "It was overwhelming."

A-Rod was visibly nervous as he took grounders before the game. He misplaced his batting glove, talked a little too fast and chewed his gum a million times a minute. "I think he was feeling the pressure to come out and make a statement on Opening Day," says Gonzalez. "He was under the magnifying glass."

Before the game, writers referred to A-Rod, who had left the Seattle Mariners to sign a 10-year, $252 million contract with the Rangers, as Mr. Two-Fifty-Two. After the game they would call him something worse: a flop. He botched a throw for one error, slipped on the artificial turf to foil a double play and then tripped on his shoelaces fielding an infield hit. The Fort Worth Star-Telegram summed up his fiasco this way: "The $252 million man wasn't even the best shortstop on the field Sunday. That distinction, at least for the day, belonged to the Blue Jays' Alex Gonzalez."

Afterward there were parties for both teams back at the resort hotel. But Rodriguez was a no-show. He was in shock. On the Mariners, his first major league team, he had played in the shadow of Ken Griffey Jr., and he suddenly missed that cover. "Alex Rodriguez is not a leader," says the Rangers' former closer, Tim Crabtree. "[He's] in his own world. There's no question about his work ethic, but as far as looking for a guy to lead a ball club, that's not him. He had too many things going on, too many priorities in his life."

That "252" became an inescapable reproach to everything Alex did. "How much is A-Rod making per strikeout? Per hit? Per trip over shoelaces? Per sunflower seeds spit or not spit?" asked Los Angeles Times columnist Diane Pucin after Rodriguez struck out three times during the Rangers' home opener two days later.

A-Rod had his motivational guru, Jim Fannin, on speed dial. Fannin, a mental coach who had worked with Orel Hershiser, Randy Johnson and Alex's Seattle teammate Joey Cora, used visualization techniques to help athletes reach what Fannin called "the zone," a perfect state of mind for performance. "Pressure is good. Pressure is fun," Alex kept telling himself, but the heightened expectations made him pace around the clubhouse, grip his bat tighter and rush throws. In his first 10 games he had only 11 hits, two RBIs and no home runs.

"He felt it," says his former Rangers teammate Bill Haselman. "He had the mentality of somebody trying to hit a three-run homer with nobody on base."

Alex had always worked hard, but he worked even harder now. He would often be in the batting cage for an hour after games. He studied all the scouting reports and exhibited a voracious appetite for the nuances of the game. From his position at shortstop he stole the opposing team's signs to detect when a hit-and-run was on. He practiced throws from every conceivable position, right down to a bare-handed dive for the ball followed by a twist and throw from his knees. "I'm like, 'Wow, dude, why would you even practice that?' " recalls former Rangers teammate Mike Lamb. "And then, that night, the exact play happens. You watch stuff like that, and it ruins it for us mere mortals."

In the Rangers clubhouse Alex was in constant motion from the moment he arrived -- at noon for a 7 p.m. game -- until well after the last out. He'd sometimes watch game film till 3 a.m. One ex-Ranger says Alex was "the only player I ever knew who would turn up the volume on a game tape to hear what the commentators were saying about him. If they said he was great, he'd hit the rewind button to listen to it again."

Alex's obsession had obvious on-the-field benefits. "He was aware of everything," says Haselman. "He was aware of guys trying to steal signs, of guys taking too big a lead. He was aware of how important it is to hold a guy on second with one out, not letting him steal third -- the little things that don't show up in stats. In that regard he was tremendous. He knew the pitches [that were] coming."

This attention to detail cut both ways, though. During his three seasons in Texas, former Rangers say, A-Rod would also use his insider's information against his own team. In games that were lopsided (and for the Rangers, there were plenty), Alex would occasionally violate a sacred clubhouse code: From his shortstop vantage point, he would tip pitches to the batter at the plate in a quid pro quo. It would always be a middle infielder, who could reciprocate -- "a friend of his, a buddy who maybe had gone 0 for 3 and needed a hit," says one former player. "Alex would see the catcher's signs. He'd signal the pitch to the hitter, do a favor for him. And down the line, Alex would expect the same in return."

According to ex-Rangers, here's how the pitch tipping worked: The game is out of hand -- say, one team has an eight-run lead in the late innings. Alex picks up the pitch and location signs being flashed by catcher Pudge Rodriguez. This is normal for shortstops, the quarterbacks of the infield, who often use the knowledge to align the defense. If a scouting report indicates a hitter will pull a curveball, a signal by a shortstop to his defense helps infielders adjust.

The key questions are: When is the signal given, and how is it delivered? A shortstop's cue to the defense is usually subtle -- a hand slipped over a kneecap, a jab step forward -- and it coincides with the pitcher's windup. This way, the hitter cannot pick it up. His eyes are on the pitcher's release.

Some Rangers say that at times Alex's cues appeared to be more conspicuous, suggesting that he was conspiring with the opposing batter. Before the Texas pitcher's windup Alex, with his left arm hanging by his side, would twist his glove back and forth as if turning a dial on a safe's lock. Then the hitter knew a changeup was on the way. Alex would also sweep dirt with his cleat to tip a slider to the batter. And he would stretch his back and lean left or right to let the batter know if the pitch was going inside or outside.

"It wasn't like he did it to throw a game -- that wasn't it at all -- but he did it to help himself," says a former Ranger. "He didn't care if it killed his own guys. It was about stats for Alex: his."

Alex expected the same courtesy. If he was having an off night near the end of a meaningless game, he could look to a buddy in the middle infield for a sign. "Here was the game's best player, and yet he felt he needed this," says a former player.

Neither Texas nor any opposing team was ever in on these tipping conspiracies. In fact they were detectable only because of repetition over many games and because Alex's mannerisms were so animated. The few Rangers who were aware of the tipping, however, were maddened by it. Even if the buddy-ball Alex was playing with a small circle of opposing players meant only a dozen extra hits for him and his pals during a long season -- a home run here, an RBI there -- that's a dozen moments when an inning might be extended or a pitcher's psyche might take a hit.

So if a small group of Rangers believed Alex was betraying his own guys, why didn't they do anything about it? Most saw a great risk in confronting Alex. They were certain Alex would go running to owner Tom Hicks to squeal on his accusers.

At least one Ranger did caution Alex. "I think you're signaling a little too soon out there," he said.

"What are you talking about?" Rodriguez said in reply.

"The batters, they see you."

The conversation continued, and on the surface Alex accepted the critique. Behind the scenes, however, he was enraged at being scrutinized by anyone in his clubhouse. But he didn't change his ways. "He talks about how pressure in Texas made him do certain things," one former Ranger says of Alex, who would later blame his steroid use in Texas on the expectations he felt because of his record-breaking contract. "Well, plenty of guys have faced pressure without undermining their own teams."

Often the pressure on Alex was self-induced. On April 6, 2001, nine days before he was to visit Seattle for the first time since he had dumped the Mariners, a letter addressed to officials at Boeing, which was contemplating a move of its base of operations from Seattle to Chicago or Dallas, was published in business journals. "I moved to Dallas-Fort Worth to improve my future," the letter began, "so should you." It was signed, "Alex Rodriguez."

The letter was a clever promotion for Dallas, but it incensed many Seattle fans, who didn't need much to stoke their A-Rod animus. "I don't care what comes out of their mouths," Alex said. "I still love them."

The feeling was not mutual. Alex arrived in Seattle on April 15 and was greeted graciously -- at first. When he went out for dinner that night, he braced himself for boos that never came. But when he walked onto Safeco Field the next day, the retractable roof was open as wide as the cranks and pulleys allowed. "Alex doesn't like to hit with the roof open," Mariners president Chuck Armstrong told reporters earlier that week. "If we can possibly leave it open, we'll leave it open."

Alex slept fitfully the night before the game and talked to Fannin several times the next day. When Rodriguez's name was announced in the first inning, it was greeted with a cascade of boos... and thousands of counterfeit bills that fluttered down to the field from the upper balconies. It appeared that every stack of Monopoly money within 30 miles of Safeco Field had been tossed his way. Signs written in Magic Marker, crayon and craft paint were flashed from the seats: ALEX, BUY ME A HOUSE and WHO LET THE DOG IN? and A-FRAUD.

After the game Alex tried to laugh off the boos, but they seemed to have affected him at the plate. In that three-game series in Seattle, he went 3 for 12 with two strikeouts and one RBI. The Mariners won two of three and led the AL West with an 11-4 record. The Rangers were second at 8-8, but they would go on to lose 20 of their next 26 games.

Not even A-Rod could lure people to watch a team this bad. As the Rangers' team ERA ballooned to a league-worst 6.38, fans turned their attention to the upcoming Cowboys season and local TV ratings slid. Johnny Oates resigned as manager after the first month. Alex shook off his slow start in mid-May and got his average up to .308, but skeptics delighted in pointing out that he was only .260 with runners in scoring position at that point in the season.

On June 8 the Rangers were 27 games behind the first-place Mariners and getting pounded on the field and in the papers. Thomas Boswell of TheWashington Post called the Rangers' lone-star plan built around A-Rod "idiocy." Jack Curry of TheNew York Times wrote, "This is the home of the Texas Rangers, the team that can't. Can't win, can't pitch and can't fathom how a season that they thought would be exciting, perhaps memorable, has been a disaster. Can't believe this debacle happened after they signed Alex Rodriguez for 10 years, for $252 million."

Alex Rodriguez is blessed with a museum-worthy swing, an angler's snap of the wrist on his throws and an impeccable instinct for damage control. He needed all three of those special attributes to survive another trip to Seattle, for the 72nd All-Star Game in July 2001.

He deftly defused the hostility of Mariners fans with a heartfelt -- not to mention ingenious -- plan he had hatched a week earlier. He told American League manager Joe Torre about it, but few others. In the first inning, as spectators were getting comfortable in their seats at Safeco Field, the "home team" AL players jogged out to take their positions. Alex was the starting shortstop, and beside him, at third, was Cal Ripken Jr. This was Ripken's final All-Star Game -- the 19th of a 20-year career -- but his selection had been based more on sentiment than on merit. One of the greatest shortstops in baseball history, he had switched to third base before the 1997 season to accommodate a changing of the guard in Baltimore. Ripken was stirring the dirt around third with his cleats when Rodriguez walked over and nudged him ever so gently toward his old position.

"Here, this is yours," A-Rod said. "Why don't you go play an inning at short?"

Ripken looked at Torre in the dugout waving him over, saw the Seattle fans snapping photos, felt Rodriguez's glove on his back, noted the TV crews shooting the scene -- and had one searing thought. "I didn't want to play short," he recalls. "There was a realization that I was miked and he was miked. I really wanted to tell him, Get out of here and stop bothering me with this."

Ripken had prepared himself to play third that night, not short, in front of millions of people. Cal and Alex were alike in their polish and poise, but they had another trait in common: Neither man ever wanted to look bad. "It's the focus, and no player wants to go out there, be unprepared and potentially be embarrassed," Ripken says. He had added length to his glove when he moved to third, to flag hot grounders to his right or left. And he knew the roomy webbing would make any fast-twitch double-play attempt from shortstop feel as if he were reaching into a mailbox for the ball.

Ripken looked at Alex in disbelief but knew what he had to do. As he walked over to short, he turned to AL starting pitcher Roger Clemens and yelled, "O.K., looks like you gotta strike everybody out."

Ripken wasn't tested at shortstop that inning, and he moved back to third base the next time the AL players took the field. "The deeper meaning was that it was a wonderful gesture," Ripken says. And, as he would later acknowledge, the switcheroo played well with the audience.

Everyone got what he needed. Ripken was rightly honored; the crowd got to savor an emotional moment; and Alex was feted for his generous spirit.