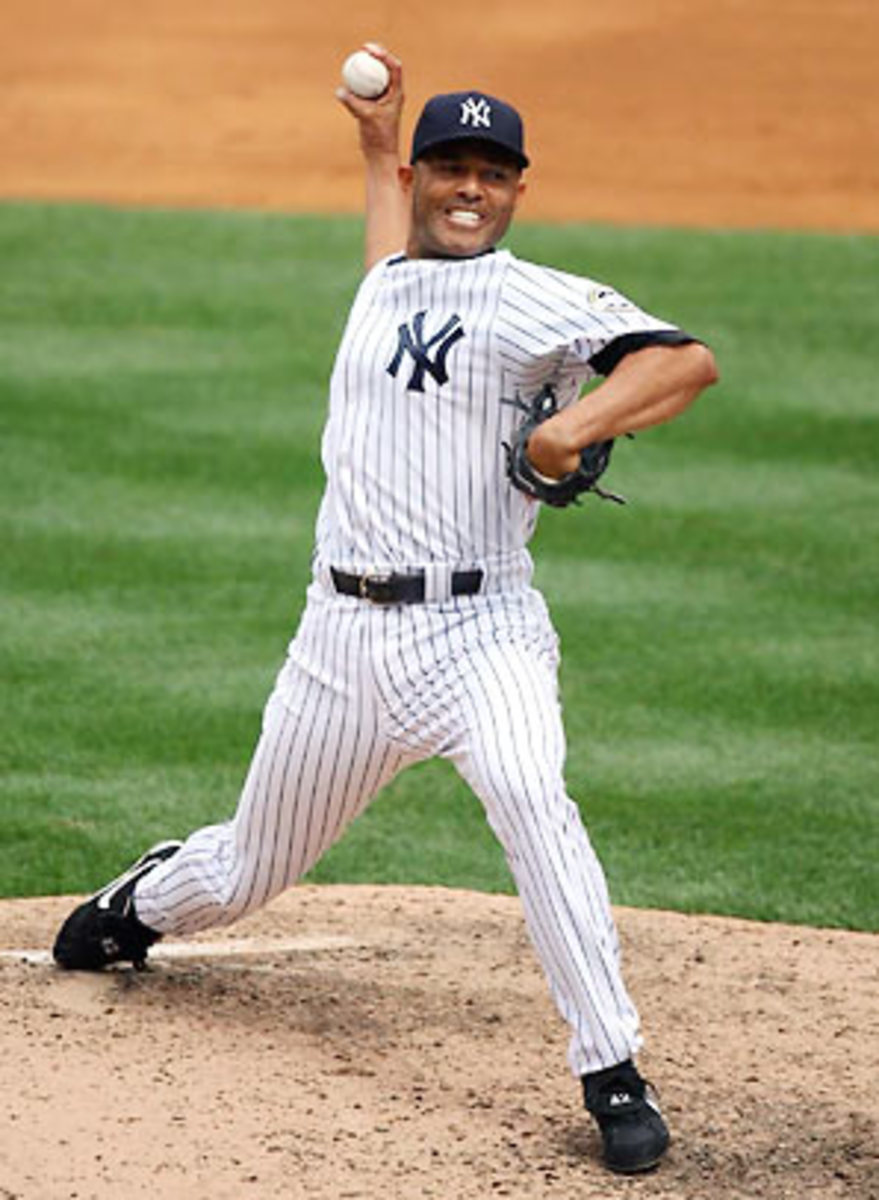

Mariano Rivera's a true Yankee, almost mythical in his dominance

There is a Yankee mythology that sustains New York fans and drives everybody else crazy, and it goes something like this: To play for the New York Yankees, you need to have a certain quality -- quiet dignity, maybe, that's part of it, or valor or a sense of the moment. All of that. More. To be a Yankee, the mythos goes, you should suffer your pain in private like Mantle, and keep hitting home runs even when your hair falls out like Maris, and find your true self in October like Reggie. You can be larger than life, like the Babe, and call yourself lucky when dying like Gehrig, and see the world through your own eyes like Yogi. You can even punch out marshmallow salesmen like Billy Martin. As long as you win almost every time out, like Whitey, and make perfectly timed moves, like Casey, and are willing to dive headfirst after victory like Jeter.

No team has so many legends ... and no team celebrates their legends to New York Yankee excess. This is what makes the Yankees so beloved and despised, depending on which side of the pinstripes you stand. And the man who probably represents the Yankee mythology better than anyone is the man who, according to the Yankee legend, never threw to the wrong base. "I thank the good Lord for making me a Yankee," Joe DiMaggio famously said, and he hit in 56 straight games and made plays with grace. People wrote songs about him. Hemingway wrote literature about him.

"I must have the confidence," Hemingway's old man says to the sea, "and I must be worthy of the great DiMaggio, who does all things perfectly even with the pain of the bone spur in his heel."

The funny part is there is actually a Yankees player who, perhaps even more than DiMaggio, lives up to the Yankee mythology. He too is the son of a fisherman, and he grew up poor enough to understand. His career almost ended before it began, and he was almost traded (twice) before the Yankee pinstripes looked right on him. On the field, he has triumphed under the most intense glare in American sports. Off the field, he has been quiet to the sound of invisible. And all the while, he has looked calm, stunningly calm, the sort of superhuman calm that Hollywood gives its heroes.

Yes, if there is an expression that conveys the Yankee myth, it would be the countenance of Mariano Rivera in the ninth inning.

"Have faith in the Yankees, my son," Hemingway's old man says to the boy. "Think of the great DiMaggio."

If Ernest Hemingway was alive and writing today, those words would be: "Think of the great Rivera."

*****

One pitch. Think about that. Mariano Rivera has saved 502 baseball games by essentially throwing one pitch, that same cut fastball. And, of course, he has done much more than save 502 baseball games with the cut fastball ... you can choose a thousand numbers to show his eminence. Consider ERA+, a statistic that measures a players ERA against the pitchers of his own era. In ERA+, 100 is exactly league average.

Here are the greatest ERA+ in baseball history (more than 1,000 innings pitched):

1. Mariano Rivera, 198 2. Pedro Martinez, 154 3. Lefty Grove, 148 4. Walter Johnson, 147 5. Five pitchers tied at 146

Look at that -- Rivera's ERA+ is more than FORTY POINTS higher than anyone else in baseball history. How about WHIP -- walks-plus-hits per inning pitched?

1. Addie Joss, 0.968 2. Ed Walsh, 1.000 3. Mariano Rivera, 1.02 4. John Ward, 1.044*

*You will note the other three on the list are all pitchers from the Deadball Era.

How about number of seasons with an ERA under 2.00? Walter Johnson did it 11 times -- all in the Deadball Era. Mariano Rivera did it eight times during the biggest explosion of offense since the 1930s. Of course, you can't compare Rivera to Walter Johnson or any other starter; Rivera has not even thrown 85 innings in a season since he became a closer in 1997.

Then again, you cannot compare Walter Johnson or any other starter to Rivera either because of the 1,055 innings the man has pitched, about 900 of them were eighth inning, ninth inning or later, with the game on the line, with the crowd freaking out, with the metropolis tabloid editors holding the back pages (How's this for the headline: "Cry Me A Rivera?" Or "Oh no Mariano!"), with the opposing team, as it says in Casey at the Bat, clinging to the hope which springs eternal in the human breast.

And with Rivera on the mound, Mighty Casey did strike out time and time and time again. Rivera struck them out and busted their bats on that same pitch over and over and over, one pitch, a low-to-mid-90s cut fastball. One pitch. It seems impossible.

But what a pitch. Jim Thome calls it the greatest pitch in baseball history, and who could argue? There's Sandy Koufax's curveball, Satchel Paige's fastball, Steve Carlton's slider, Carl Hubbell's screwball, Bruce Sutter's splitter, Gaylord Perry's spitter, Pedro Martinez's change-up, but all of them threw other pitches, set-up pitches. Rivera has no opening act. He comes at hitters with the same pitch, one pitch, again and again, hard fastball, sharp break to the left at the last possible instant, that pitch has undoubtedly broken more bats per inning than any other, it has left more batters frozen per inning than any other, it has broken more hearts than Brian's Song.

Rivera says he learned the pitch while fooling around one day in 1997, playing catch with his friend and Panama countryman Ramiro Mendoza. By then, Rivera was already the Yankees closer. And he was already terrific -- he was coming off a superhuman 1996 season. That year, as a setup man to John Wetteland, he had pitched 107 innings, struck out 130, and allowed the league to hit only .189. But he had done that with pure power -- a high-90s fastball and impeccable control. And such things don't last.

Rivera remembers playing catch with Mendoza, coming up with a new grip, and coming out of it with this monster -- "A gift from God," he always says -- a cut fastball that bore in on lefties and made righties give up.

And suddenly, he was even better. That year, 1997, he finished with his first sub-2.00 ERA. And from that point on, Mariano Rivera threw that one pitch in ballparks across America, to the best hitters of his generation. The best hitters of his generation could not catch up. They have not caught up still.

"You know what's coming," a five-time All-Star Mike Sweeney once said. "But you know what's coming in horror movies, too. It still gets you."

*****

Mariano Rivera grew up in Puerto Camito, Panama, and he happily will admit that he did not grow up with big dreams. He never expected to leave. He worked as a fisherman as a young boy -- cleaned fish, pulled up nets, like the boy in Hemingway's vision. He wanted to play ball. The Yankees signed him for $3,000, Rivera promised his mother he would always come home, and when he was 22 years old he had Tommy John surgery. Nobody was predicting great things.

His first game in the big leagues in 1995 -- Rivera was 25 already -- he started against the California Angels and lasted just 3 1/3 innings. After four starts, his ERA was 10.20, and he didn't pitch again for more than three weeks. Then, on the Fourth of July, he threw eight innings, allowed two hits and struck out 11 against the White Sox. The Yankees were not entirely sure what they had.

They would not really know what they had until (fittingly) the playoffs -- the Yankees first playoff appearance in 14 years. Rivera pitched 5 1/3 scoreless innings in relief against the Seattle Mariners. He dominated those innings too, something seemed to light up inside him when the pressure was its heaviest. The next year, with Joe Torre as the new Yankees manager, Rivera was moved to the 'pen, and he was immediately so awesome that in late April, Twins manager Tom Kelly made his statement: "He needs to pitch in a higher league, if there is one. Ban him from baseball. He should be illegal."

Of course, quite a few closers have been virtually unhittable for one year, two years, three years. But sooner or later, something happens. Hitters figure something out. The constant duress wears the pitcher down. The closer's money pitch loses one mph of speed or one millimeter of break. And then, like an NFL cornerback who loses a half step, the closer is lost.

But Rivera's one pitch has never lost its power. He just keeps going, year after year. Here's a challenge for you: pick out Mariano Rivera's best year. Do you want 1998, when he saved 36 games for the almost unbeatable Yankees and posted a 1.91 ERA? Or do you prefer the next year, when he led the league with 45 saves and opposing batters hit .176 against him? Do you like 2004 when he saved 53 -- 32 by the All-Star Break -- or 2005 when he had a 1.38 ERA and had an absurd 38 1-2-3 innings?

Then again, you could always choose last year, when Rivera had a 77-to-6 strikeout-to-walk ratio and punched up a .665 WHIP -- only Dennis Eckersley in his heyday had ever put so few batters on base.

He has always looked so comfortable in the moment. It isn't that Mariano Rivera has never failed -- he actually has three of the most famous defeats in recent memory. In 1997, he gave up an eighth-inning home run to Sandy Alomar with the Yankees just four outs away from clinching a spot in the ALCS. In 2001, he gave up two broken bat singles -- Rivera breaks bats the way Chuck Norris breaks bones -- and committed an error and allowed two runs in the ninth in Game 7 of the World Series. In 2004, he blew two saves against Boston, a performance so shocking that the next year Red Sox fans wildly cheered him when his name was announced.*

*Rivera just smiled, of course. "I felt honored," he said. "What was I going to do? Get upset and start throwing baseballs at people?"

No, it isn't that Rivera never failed, it's that he never let that failure define him or knock him off course. Even with those three defeats, he's the greatest postseason closer in baseball history, maybe the greatest postseason pitcher ever. He is 8-1 in the postseason with 34 saves (nobody else has even half of that) and a ludicrous 0.77 ERA. Sixty-six times in his postseason career, Mariano Rivera has appeared in the late innings of a playoff or World Series game and not given up a run -- nobody else is even close.

Rivera does not talk much about it, at least not publicly, but he will say that to pitch well in those heart-pounding moments you have to enjoy the heart-pounding moments, you must have balance in your life (the moment is important but not THAT important; losing is difficult but it won't kill you), and you have to forget the failures and successes of the past. Rivera does not seem the type to write a book, but if he ever did it should be something about peace -- Zen and the Art of Closing Out A Baseball Game -- because that seems to be his greatest gift of all. Mariano Rivera always seems at peace.

*****

It's probably worth noting here that Mariano Rivera has not written a book. Other Yankees have -- Derek Jeter has written two, Paul O'Neill wrote one about his father, Jorge Posada has written a children's book and so on. Rivera doesn't claim to have anything to say. He seems happiest in the stillness of the background, a hard place to find in New York City.

But he has found that quiet place in New York. And this, perhaps, is the most remarkable thing about Mariano Rivera. He's the ultimate Yankee, the embodiment of the Yankee myth, and yet for 15 seasons now he has not sparked a controversy, not been caught in the bright lights, not inspired the boos anywhere in America.

Oh, every so often, for a couple of weeks or a month, he will give up a few runs and look to be human, and there will be some who will start to prepare the eulogy, most recently a few weeks ago after a rough patch, but then he will emerge again, throwing that one matchless pitch. He's 39 years old now. He has saved 48 games in his last 50 chances. This isn't to say that Mariano Rivera is underrated -- everyone knows. Yankees fans love him. Opposing fans respect him. It's just that as good as people think he is, he might even be better.

He comes into a game -- Metallica's Enter Sandman blaring over Yankee Stadium -- and he begins to warm up, and the crowd's going wild, and the opposing players are psyching themselves up, and he has that look on his face, that placid look, that look that says that everything will be all right.

"They have other men on the team," the boy said to Hemingway's old man.

"Naturally," the old man said. "But he makes the difference."