Talkin' about baseball, and watching a game, with Bill James

One of the many things that strikes me about Bill James -- who is just one month away from his 60th birthday -- is that his mind never stops whirling. Here we are watching an astonishingly boring game between the Cleveland Indians and Kansas City Royals last week, and suddenly, out of nowhere he says this:

"You know one little way in which baseball changes us? We don't even think twice about Japanese names anymore. You know what I mean? Remember how foreign those names used to sound to us a few years ago? But now I can think about Masahide Kobayashi and it just feels familiar, you know what I mean?"

I do know exactly what he means. And yet ... I look down on the field and notice that there are no Japanese players in this game. So where does this thought come from? What is it that sparks this particular musing at this particular time? Bill doesn't know and doesn't particularly care to think about it. It's just how his mind works.

Pretty much everyone knows Bill James by now. He is the only writer ever to be hired by a major league baseball team, featured by 60 Minutes, studied by the U.S. military and named by Time magazine as one of the world's 100 most influential people. You know the old line that only a few thousand people bought a Velvet Underground album, but every one of them started a band. So it goes with Bill James. He always had more popularity than people expected -- he's a multiple-New York Times best-selling author. But his influence trumps his popularity. Bill James has changed the way people think about baseball in a hundred different ways.

"I don't know," he says about all that. "Maybe a few less people say that pitching is 90 percent of baseball." This was one of his breakthrough observations. For years, people around baseball would utter this mathematical piece of nonsense -- pitching is 90 percent of baseball -- and it took Bill James to ask: "What the heck is THAT supposed to even mean?" He then destroyed the concept, brick by brick, but just in asking the question he got people to smile and realize that, wow, pitching as 90 percent of baseball is one ridiculously stupid concept.

"You know what I wish people would stop saying?" he suddenly asks ... and once again his mind goes in a whole other direction. Bill has just finished writing a true crime book -- a million thoughts on crimes from Elma Sands to the Kennedy assassination to JonBenet Ramsey -- and his mind has locked in on another seemingly ridiculous thing: People always talk about the eyes of serial killers. The eyes. You can see it in their eyes. There's horror in their eyes.

"That's just nonsense," Bill says. "Nonsense! Do people really believe there's something different about the eyes of murderers? Their eyes look like everyone else's eyes. And this is dangerous nonsense because it makes people believe that they can look in someone's eyes and determine guilt or innocence."

Yes, the mind never stops working. The questions never stop coming. This seems to be one of the things that makes Bill different ... most of us hear a cliché like "There was something dark in the murderer's eyes," and it just rolls right over us. We don't -- or at least I don't -- stop to ask what it means.

But for Bill James -- who has spent his life asking questions -- it's just natural to heard him ask, "Are you saying that there was a black spot in the eyes of the guy who committed the murder? Or was it a gray cloud?"

* * *

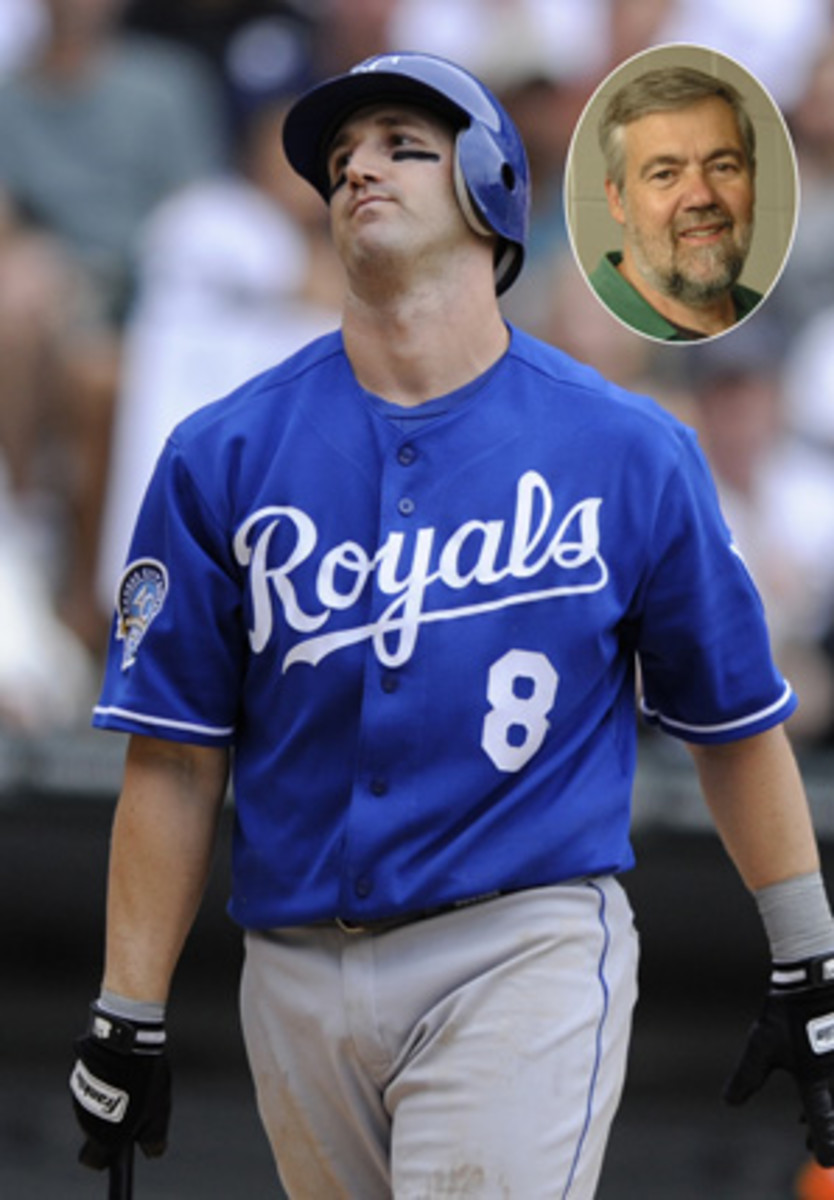

The Cleveland-Kansas City game has little action, which is not unexpected. The Royals -- Bill James' favorite team until he started to work for the Boston Red Sox back in 2003 -- are a million games back and are well on their dead-man walking march to 100 losses. The Indians -- my favorite team when I was young -- are only a few games ahead of the Royals and seem only slightly more interested in the ongoing season.

"The problem is the idea of professionalism," Bill says, while we watch Kansas City's Willie Bloomquist ground out to second. This has been an overpowering thought for Bill the last few years -- his idea is that for all the good that has come from it, "professionalism" has taken a heavy toll on American society. "Cops became police officers, but the crime rate soared," he wrote in the New Historical Baseball Abstract. "Professionalism in law has brought us the O.J. Simpson case in lieu of justice. ... Professionalism in medicine has given us medial miracles for the affluent but hospitals that will charge $35 for aspirin."

In baseball, he thinks the pursuit of professionalism has made teams like the Kansas City Royals second-class. The Royals don't have enough money to compete the same way as the Red Sox, Angels or Tigers. A short boxer cannot win using the outside jab. A quarterback with a weak arm will not win by throwing deep. A 5-foot-10 basketball player cannot make it to the NBA with a back-to-the-basket game. The one sure way that the Royals will lose is by using the same blueprint as the New York Yankees.

And yet ... that's what the Royals (and other small market teams) do. They play the game conventionally. They fall back on old ideas. They hire old school managers and preach old school baseball values and scout players on the same 20-80 scale that players have been scouted for 50 years. Bill pulls out his spiral notebook -- he always brings a spiral notebook to games -- and on a page he draws two ladders, one on top of the other. The higher ladder is the "professional" ladder. The lower ladder he calls the "amateur" ladder. He then draws a picture of someone dangling from the bottom rung of the professional ladder. That, he says, is the Kansas City Royals.

"It's so important for them to be considered professional," he says, "that they are unwilling to try anything that might make people think they're amateurish."

Bill then says he could come up with 10 unconventional questions right on the spot that a team like the Royals should at least ask themselves. What would happen -- for instance -- if the Royals decided that they would get rid of every pitcher in their system that threw 90 mph or faster? Ludicrous? Sure. But what would happen? Bill didn't claim to know what would happen, but he's quite certain that nobody else knows, either. Maybe the Royals would find that guys who top out at 83-mph cannot get out big league hitters. But maybe instead they would find a whole new way of scouting pitchers because they would have a virtual monopoly on those slower-throwing pitchers. They would be able to sign THE BEST 83-mph pitchers (rather than the 95-mph pitchers that other teams don't want). Maybe they would find all these pitchers with incredible command, pitchers with a wild assortment of pitches, pitchers who have figured out how to get hitters out because they could never rely on simply overpowering them.*

*A few days later -- after Paul Byrd shut out the Blue Jays on Sunday -- Bill sent along this e-mail: "Red Sox called Paul Byrd out of retirement to make a start this afternoon, and he was dynamite, throwing about 84. Had the Blue Jays hitting off the wrong foot all day."

Is Bill saying that the Royals or the Reds or the Pirates or the Nationals really should do such a thing? No. He's saying that they would never even THINK about doing such a thing because it would look unprofessional. People would laugh. And that potential laughter keeps teams like the Royals locked in their boxes, a permanent baseball underclass clinging to the ever-fading hope that (through luck and instinct and, yes, professionalism) they might collect enough good players to contend for a little while.

The Royals are on pace to lose 100 games for the fifth time in eight years. The Pirates have had a losing record every year since 1993. The Reds will have their ninth consecutive losing season this year. The Baltimore Orioles lost the American League Championship Series in 1997 and have not won 80 games in a season since.

To Bill: That's professionalism at work.

* * *

Kansas City's Miguel Olivo grounds into a double play, and I'm reminded that a day earlier Olivo had run off the field with two outs in an inning. It was the sixth or seventh time this season that I had seen a Royals player forget the number of outs -- I suspect the Royals lead the league -- though this one time was particularly funny because Olivo is a catcher ... and only two batters had come to the plate.

"You know," Bill says, "if I was a player, I'd forget the number of outs all the time. I'm amazed at how focused these athletes are over a long season."

This is a part of Bill that people can miss. He has come up with so many baseball concepts -- win shares, runs created, range factor, the Hall of Fame monitor, the Pythagorean win percentage, secondary average, similarity scores, on and on and on -- that people tend to think of him as a slide-rule-in-the-front-pocket nerd. And he has written so acerbically about players and managers (some of this embarrasses Bill) that people tend to think of him as a grump.

But Bill doesn't love baseball statistics. And he isn't cynical, either. No, it's just that Bill doesn't accept anything at face value. He believes every single thing should be questioned and then questioned again and then questioned again. The world is a big and complicated place. Baseball is a big and complicated game. We can't understand it all ... and what has driven Bill James for most of his life is just that, bursting the arrogance of anyone who thinks (even for a moment) that they have it all figured out.

Still ... he does love baseball. He loves the stuff that some people might not think he loves -- the smell of the grass, the crack of the bat, the nicknames, the chatter on the field, the way strangers talk to each other in the stands. He figures baseball statistics because he would like to get a little closer to the truth. And on occasion he can come across as harsh because he does not suffer fools, and he is allergic to the stuff my father always called "baloney."

But he still gets a thrill out of baseball games, even lousy ones like this game. He likes to observe different batting stances. He likes to think along with a pitcher. He likes the rhythm of a game that just goes along, slow drumbeat, and then suddenly crescendos with a fantastic moment.

"That was a great play," he says as he applauds the Royals throwing out Cleveland's Jamey Carroll at the plate. Kansas City's center fielder Mitch Maier had made a nice throw to shortstop Yuniesky Betancourt who had made a solid throw to catcher Olivo, who placed the tag on Carroll. You would mark it 8-6-2 in your score book, but that's the thing. Bill isn't keeping score.