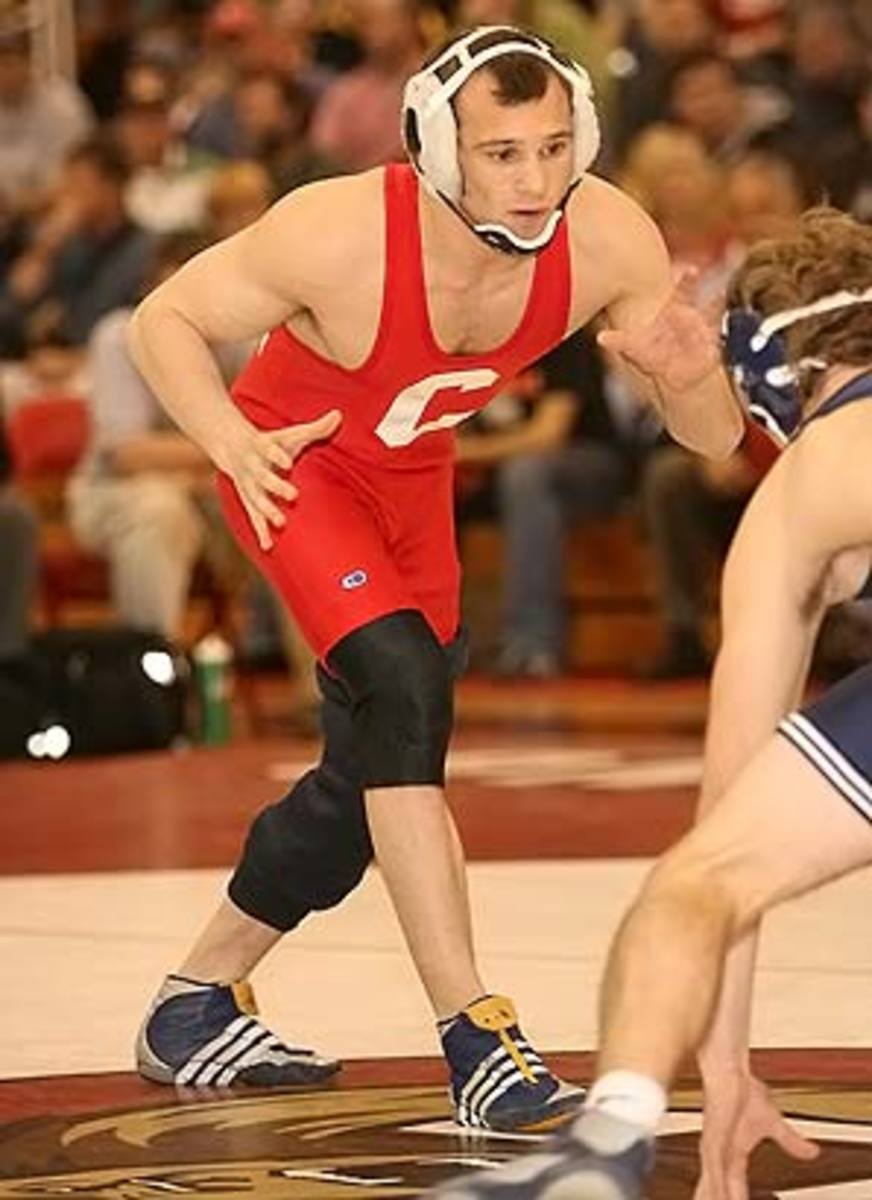

Adam Frey is grappling with his toughest foe, and holding his own

Adam Frey, the 2005 national junior Greco-Roman champion and the 2007 Ivy League wrestling rookie of the year, is wearing a long-sleeved sweatshirt and ski cap, standard garb for the weight-cutting jock. Indeed, for much of his young life 23-year-old Adam has spent the off-season shedding avoirdupois to one degree or another. But these days calories are the last things he wants to lose. He is bundled up because he feels cold, even though it's summer in his hometown of Pittsburgh.

That's no more unpleasant, though, than when he finds himself sweating profusely, which happens often during the night. "Some mornings after he gets out of bed," says his mother, Cindy Frey, "I just wring his sheets out." Adam, who now carries about 140 pounds on his 5'6'' frame, has lost as much as eight pounds as he tosses and turns, and sometimes he just gets up and sleeps somewhere else.

He has mouth sores. His fingertips are extremely sensitive to hot and cold. Often he feels disoriented, "not myself." Sometimes he has an intense desire to eat, but, when food is placed in front of him, he gets nauseous. Egg whites are about the only comestible that he can truly depend on. He has lost hair on his head and face. He despises the button-sized mediport that protrudes from the right side of his chest -- "I used to find every excuse in the world to take my shirt off," Adam says -- but the worst part is what people can't see: The mediport has a long tube that goes over his collarbone into his jugular vein.

Yes, Adam's twin set of cauliflower ears, the wrestlers' gladiatorial badge, don't seem like much of a problem these days, not while he's fighting a multiple-front battle with germ cell testicular cancer, taking it on with a brutal regimen of chemotherapy, one kind of poison trying to beat back another.

The war within him has been going on for about a year-and-a-half now, and, through it all, Adam has remained fist-shakingly, defiantly positive. "I'm going to beat this thing," he says. "The odds are long. But I'm going to beat it."

On March 25, 2008, a few days after his sophomore wrestling season at Cornell had ended with a loss in the NCAA championships, Adam walked away from a bad car accident in Ithaca only to discover, after the routine CAT scan, that his body was racked with cancer. Lesions were found on his lung and liver and in the lymph nodes of his abdomen, along with a bowling-ball-sized tumor between his kidneys. He had never smoked, chewed tobacco or done street drugs. "My body was what I depended on," he says. He was declared to be at Stage 3 -- inoperable and radiation-resistant. "All things considered," says Adam, "the prognosis couldn't have been much bleaker."

Sixteen months later, Adam is still here, his life an endless cycle of hospital visits, chemo treatments, cancer counts, injections and medical consultations. "I know way more than I ever wanted to know about cancer," says Adam. It goes without saying that someone this young should not have to endure such agony, but an older someone shouldn't have to, either.

Adam will admit to some why-me? moments along the way. But they don't last long. "He's hard-wired to compete," says his father, Jerry. "He doesn't know how to do anything except all-out." Adam has started the Adam Frey Foundation to raise money for cancer research -- the Adam Frey Classic held in July at Rider College raised about $15,000, and he hopes it will be an annual event. He reaches thousands of readers on his blog (adamfrey.us), on which he rarely sugar-coats the agony of his treatment but also manages to find some humor, as when he wrote of the day that he had to provide a sperm specimen at a women's hospital. "So there I was, the only male patient in a woman's hospital," wrote Adam. "You might as well put a sign on my head saying, 'Only here to masturbate.'"

Each entry brings hundreds of heartfelt responses. "He has touched many of us in ways that being an NCAA champion or multiple time AA [All-American] never could," wrote one reader. "... Everyone who reads it will be moved by his journey."

With his cancer counts in check of late, Adam has begun working out again, though muscle pain and the necessity of taking it easy have hardly made the experience pleasurable. "I'm an all-or-nothing person," he says, "so if I go into the gym, next thing you know, 225 pounds is on the bar. I have to watch that."

He talks of returning to Cornell for the spring semester of 2010, and, at times, has even contemplated a comeback to the mat, where he virtually lived from the age of six. He knows it might be a pipe dream, but, well, look at the odds he's already defied. "I'm supposed to be dead," says Adam. "In fact, I was dead." In October of 2008 he was suffering from full-body staph infection, his temperature at 107.9, most of his vital organs shut down. But back he came, and he hasn't come that close to death again.

* * *

Germ cell testicular cancer accounts for only about one percent of all cancer in men, but it is by far the most common type for men between 15 and 35. It is quite curable, but what made Adam's cancer so problematic was the degree to which it had spread by the time it was detected. In all likelihood, his near-imperviousness to pain kept him from recognizing symptoms. "Hey, when you wrestle," says Adam, "something always hurts."

From the beginning of his diagnosis, Adam wanted to attack his cancer aggressively, "to go down swinging if I was going down." He is now on his fifth different kind of regimen; three of them have been experimental, either in the prodigious doses of chemo he was given or the combination of drugs that were used. "Whatever happens with Adam, he has been immensely helpful to other patients," says Dr. Leonard Appleman, an oncologist who supervises Adam's treatment at the Hillman Cancer Center in Pittsburgh.

Anyone who knows Adam isn't surprised that he's handling the treatment well. "What we can say for sure is that he tolerated high doses of chemo very well because of how fit and in shape he is," says Dr. Darren Feldman, an oncologist who specializes in testicular cancer at Memorial Sloan-Kettering in New York City, where Adam has also undergone treatment. (Feldman and Appleman are in constant communication about Adam, a team approach to treatment that is becoming increasingly common.) "And as an athlete Adam has more control over his body than the normal person and more discipline. That makes him adherent to medical recommendations. He's always told himself, 'I can do this. I can do this.' So he goes out and does it."

Adam could feel something coming long before the diagnosis. Entering Cornell in the fall of 2005 after an outstanding scholastic career at Blair (N.J.) Academy -- he was the nation's No. 1 recruit at 130 pounds -- Adam red-shirted because of a shoulder injury. He got off to an excellent start in his first competitive season in 2006, beating three ranked wrestlers in the 133-pound class. He finished 2006-07 with a 16-4 record and was named the Ivy League's top rookie. His goal as a sophomore was an NCAA championship.

But the '07-08 season was a struggle from the beginning. No matter how hard he trained -- and few trained harder than Adam -- he had trouble cutting weight. "Why do you have a gut?" his teammates and friends would tease him. "Hearing that was hard," says Adam with a smile. "I always liked the way I looked in a singlet."

It was the tumor growing. "We knew something was wrong," says his mother, "but nobody could find anything." He still won more than he lost (15-9) and qualified for the NCAAs, where he didn't place but went 2-2. But he didn't look right and he didn't feel right.

Then came the morning when he climbed into his SUV and decided to stop at McDonald's on his way to class. On a wind-blown road in Ithaca, he suddenly saw another vehicle coming toward him, veered right hard to avoid it, fishtailed and hit a tree at about 55 mph.

"It was terrible, but in a way it was the luckiest day of my life," says Adam. "If I hadn't gotten the CAT scan that day, I would be dead for sure."

Adam doesn't talk much about the specter of death. Nobody in his family does. The Freys -- mother, father, brother Garrett, also an outstanding scholastic wrestler who will compete for Princeton this winter as a freshman -- are more attack-first-contemplate-later type of people. A hotel wrestling match between Adam and his father a few years ago, for example, resulted in a broken ankle for Jerry. "Adam had me in a headlock, and I had to post my foot against the wall so I wouldn't break the TV," explains Jerry. Cindy was also an early partner for both sons. "They've broken my fingers and my nose," says Cindy. "I have a spur on my neck and they dislocated my shoulder." She shrugs. "I think that's everything anyway."

Mother and father, apart or together, have seen virtually every match in which either son has ever wrestled, no mean feat since the boys often competed on the same days hundreds of miles apart. The parents' beloved blue Cadillac had 249,000 miles on it -- "mostly wrestling miles," says Jerry -- before it finally gave out.

His family feels his pain -- that's evident when Cindy closes her eyes and determinedly squeezes back tears during dinner -- but wrestling has long been the family glue, the Frey fuel, and it's hard for any of them to imagine that, for Adam, it might be gone. Adam, in fact, is the most realistic about his chances of ever again putting on a singlet. "I'm at the point now where if I don't step on a mat, that's fine," he says. "Maybe God's plan was for me to use wrestling for another message, a message away from the mat."

Adam's immediate plans are simple: Keep fighting the cancer at Hillman, buffered with occasional visits to Sloan-Kettering. If a new treatment shows any ray of hope, he will raise his hand. Keep working out when he feels up to it. Keep blogging. Keep plugging along. Keep getting by day-by-day, week-by-week, month-by-month. Keep sucking up the agony. His long-range goals are on hold but not forgotten. He used to talk about wanting to be President, but he's now revised that downward ever so slightly. "A friend suggested that I run for the House one day," he says. "Hey, I have the charisma. I love to debate. And now I have a back story. Obviously, we'll have to see where I'm at health-wise, but it's not out of the question."

Medical reality is not Adam's friend. But he can count on the optimism of youth, an indomitable will, and the memory of a thousand battles won on the mat. "I know my life might be shorter than I once thought it would be," Adam says. "I know I probably won't get the chance to do some things I wanted to do. But I've never sat down and accepted the fact that I was going to die. And I never will."