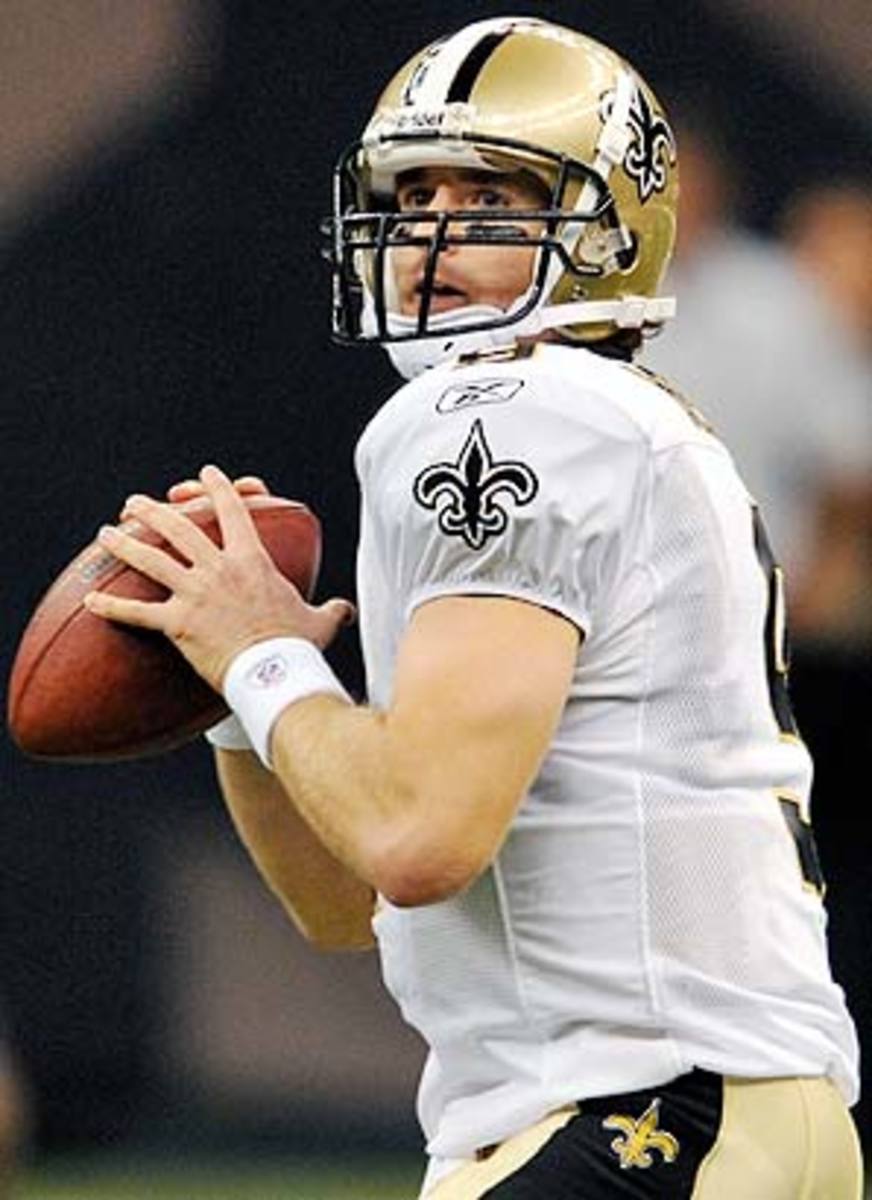

Drew Brees wants to win a championship in the worst way

On the other side of the field are the Saints, who bring quarterbacking drama of another variety altogether because Drew Brees has elevated coach Sean Payton's offense to something between Art and Madden '10. Last week the Saints accumulated 515 yards in offense and Brees threw for 353 yards and six touchdowns against the Lions in a 45-27 win in the Superdome on Kickoff Weekend.

OK, it was only the Lions. But it's not like Brees and the Saints have needed feeble defensive opposition to ring up big numbers over the last three seasons. Brees has thrown for 13,910 yards in that time, the second-highest three-season total in NFL history. (Dan Marino threw for 13,967, 57 yards more than Brees, from 1984 to '86). His career passer rating is 90.0, the ninth-best in NFL history. But in his three years-plus in New Orleans, according to pro-football-reference.com, Brees is 94.9, which would rank third in history, behind Steve Young (96.8) and Tony Romo (95.7, with a much smaller body of work).

The Saints' offense is an efficient mix of several epic NFL systems, with pieces of Bill Walsh's West Coast Offense, Don Coryell's Air Coryell (the real West Coast Offense, but that's a longer story for another day) and even the ubiquitous spread passing game that so dominates college football, minus the running quarterback. Brees is a lethal operator -- he reads and throws quickly and remains one of the most accurate passers in recent NFL history.

Of course as the Saints come into Philadelphia this weekend, Brees is nine years into a very good NFL career that's still a Super Bowl shy of validation. Brees has thrown for more than 15.3 miles and 174 touchdowns, but he's only played in three playoff games (one with the '04 Chargers and two, including the NFC Championship game, with the '06 Saints). "I'd be happy to win some games, 13-10,'' Brees told me last Sunday after the opening day win. "I'd be happy to win every game by one point more than our opponent. The type of offense we run, with the guys we have playing offense, we're going to score some points. But I don't care about that. I want to win games any way we can.''

Brees has been shredding defenses since he was 15 years old. As a senior at Westlake High in his hometown of Austin, Texas, Brees led his team to a 16-0 record and the state Class 5A championship, as big a state title as there is in the country. He went to Purdue, partly because Texas thought that the six-foot Brees was too small to play there and partly because he liked Joe Tiller's one-back spread offense. He started three years for the Boilermakers, made them a Big Ten contender and took them to the Rose Bowl as a senior.

In the spring of 2001, I shadowed Brees through the draft-preparation process as he tried to prove to the NFL that he was big enough and strong-armed enough to play professional football at the highest level. It was a rocky ride. At the Hula Bowl in Hawaii, he was measured in a room full of scouts and the attendant shouted out "Five-eleven-seven,'' code for 5-11 7/8. Brees demanded to be measured again and this time the attendant yelled "Six-even!'' and the gathered scouts erupted in applause.

(When I met up with Brees last weekend in New Orleans, the first thing I said to him was, "Don't you know you're too short to play in this league?'' Brees laughed and said, "I know. Way too short.'')

At the combine in Indianapolis he threw badly because coaches on the field gave him conflicting instructions about how to conduct himself; draftniks had him free-falling by Monday. I remember his banging the steering wheel of his SUV all the way back to West Lafayette, where he shared an apartment with his girlfriend, Brittany. She's now his wife and they have an eight-month-old son, Baylen. A month later Brees tore it up in a private audition at Purdue and a month after that, the Chargers picked him at the top of the second round.

Brees had his throwing shoulder torn up on a tackle in the last game of the of '05 season in San Diego. Dr, James Andrews told me it was one of the worst shoulder injuries he'd ever seen. Brees later signed with New Orleans, one of only two teams that was interested. Prior to the '06 playoff-opening win over the Eagles, feeding some feelgood to a post-Katrina New Orleans, we walked around a park near his home and he talked emotionally about the work to put his career back together.

That's all done now. He's got a life pass on proving people wrong. If his career ended tomorrow, he'd be considered one of the best quarterbacks of his generation. But of course that's not enough. He wants to play in February.

His offseason was spent refining his play. Hidden in the big numbers are a hundred ways to lose a game. "I have to be even more efficient,'' says Brees. "I have to protect the football on every play, convert every third down, make plays in the red zone, know when it's OK to take a sack. And I have to put other guys in a position to make the best plays they cam make.''

Example of the latter: Late in the first quarter of the win over the Lions, the Saints were leading 14-3 and faced third-and-14 from their own 15. The Lions were hanging by a thread and Brees threw a rope to Devery Henderson in the curl zone, dead at the first-down markers. But after catching the ball, Henderson gave ground in an attempt to make a big play. He was swarmed by the pursuit and came up three yards short of the first down.

Brees immediately found Henderson the sideline. "In that situation, I know we've got four guys running right at the down marker,'' says Brees. "Dev catches that ball all he's got to do is fall backwards and we keep the drive going. He's got to know that. And I've got to make sure he knows it.'' The Lions stayed alive much too long last Sunday, when the Saints could have finished them numerous times.

"Those are things that I've got to take care of,'' says Brees. "I have to know what we can't let happen on every play.''

In the end, it will come down in large part to defense for the Saints. They were given a huge reprieve this week when four-game substance suspensions for defensive ends Will Smith and Charles Grant were tabled by commissioner Roger Goodell. Without those two, an average NFL defense becomes weak and the onus falls on Brees to throw for 400 yards every week.

But know this: Brees probably has to throw for 300 for the Saints to win, and his margin for error is minimal. It's a familiar, season-long assignment for Brees and one that he's going to have to eventually fulfill to avoid being a quarterback who's remembered respectfully for his statistics and critically for his lack of championships.