As Tiger loses sponsors, it's clear athletes aren't good investment

Under the cloak of New Year's Eve, AT&T quietly dumped Tiger Woods.

Which makes sense. A man whose life has unraveled in large part because he didn't know how to use his phone isn't the ideal image for the world's largest communications company.

Tough to sell the joys of unlimited texting with an athlete whose entire world was undermined by those very messages.

With the end of the last decade -- a decade in which a man who swings a golf club became, in sequence, the first athlete to earn a billion dollars and the first billionaire athlete to derail his career by hitting a fire hydrant -- we're seeing a fundamental change in the corporate-athlete endorsement relationship.

The realization that there's very little upside.

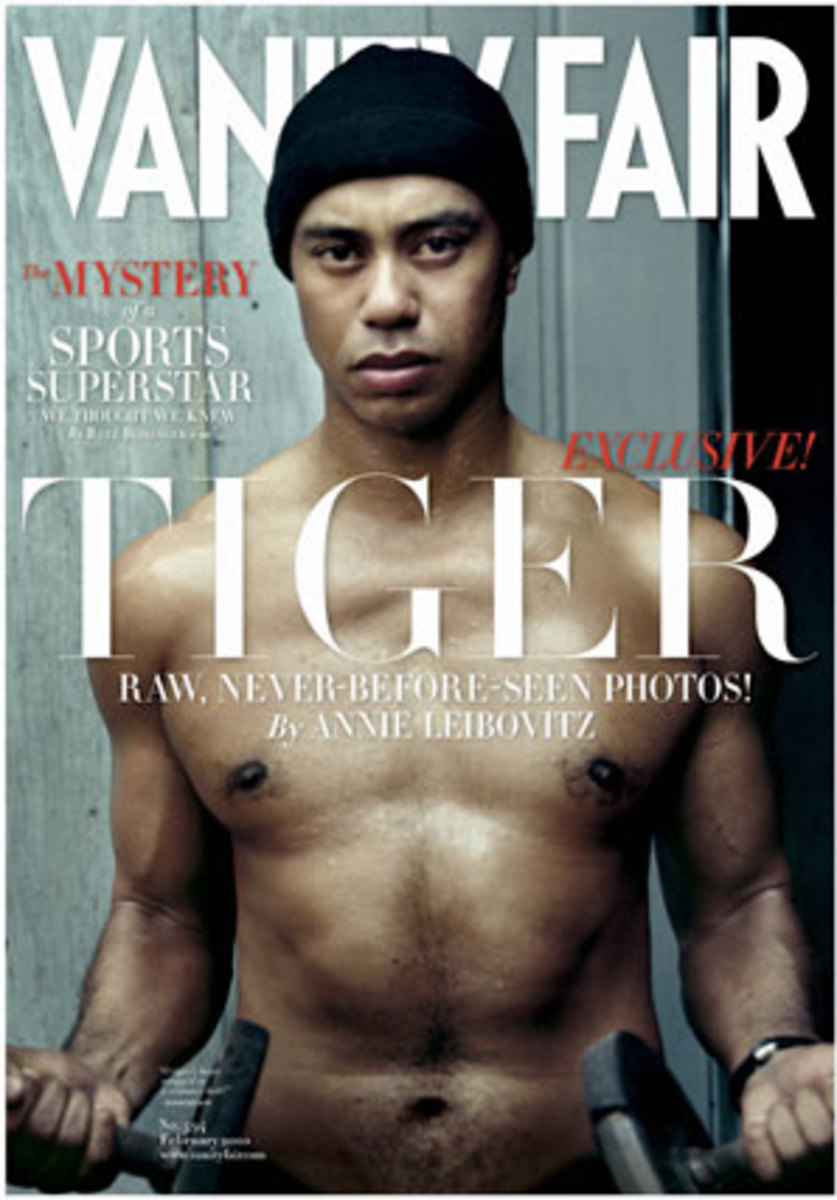

The dumping by AT&T was the final blow to Woods for 2009, but 2010 is already off to a rocky start. Unveiled this week: the new Vanity Fair cover with a four-year-old photo by Annie Leibovitz showing a bare-chested Woods lifting weights. Once surely to have been intended as sexy and powerful, the photo now conveys a creepy message.

Because the lens has changed, we'll never see Woods the same way again. AT&T and Accenture -- another corporation that severed ties with Woods -- realize that even if Nike's Phil Knight doesn't.

Knight, who linked Nike to Woods' star from the start and has invested millions in the golfer, claims that we will "look back on these indiscretions as a minor blip." But he has to say that, otherwise he has an entire line of golf gear and apparel and a multi-million dollar investment that is essentially worthless.

Nike has invested in Woods as an athlete. Same with Electronic Arts, which said this week that it would continue with an online PGA game bearing Woods' name. EA Sports has spent months and millions developing the game and likely figures that anyone interested in playing an online golf game is sure to be the audience most sympathetic to Woods.

But companies like AT&T aren't in the sports business. They don't hire athletes because of what they do on the course, court of field. They aren't catering to a customer-base of sports sycophants. They are buying the image the athlete conveys. And -- just five weeks ago -- Woods' image was shorthand for class. For cool. For excellence.

No longer.

Here in the early days of 2010, such an investment looks foolish. After a decade of drug scandals, cheating and legal troubles in sports, why would any corporation tie its image to an athlete?

There once was no safer bet than Tiger Woods. His iconic stature was such that even as the allegations poured forth, many in the sports world insisted that he was untouchable, that his sponsors would stand by him. Sports columnists and talk shows -- the same consortium that deified Woods for years - echoed Knight's view that everything would be just fine.

But it isn't fine. Not with magazine covers like Vanity Fair. Not with the speculation that will mount as the golf calendar unfolds, week by week. Not with the circus that will commence when Woods does finally show up in public somewhere.

What corporate sponsor needs that?

A study issued last week by two UC Davis economics professors claims that shareholders of Woods' title sponsors -- like Gatorade and Nike -- lost a collective $5 billion to $12 billion in the trading days following his scandal. While those figures can be debated (and in the early days of 2010 many of those losses had been recovered), the reality is that major brand names were damaged in the fallout from the fire-hydrant accident.

Corporations are going to be leery about hanging their images on the biceps of any athlete, no matter how successful or endearing that personality seems.

And athletes should be equally careful about selling themselves so easily. About constructing a false front that can easily shatter and leave them vulnerable and -- horrors! -- human.

The only safe athlete is one whose story is complete. Babe Ruth, anyone?