Story, not just numbers, often determines Hall chances

Sportswriters have a saying: we don't root for teams, we root for the story. And since sportswriters decide on most of the inductees for the Baseball Hall of Fame, it is important to keep that in mind. Most elections, for better or worse, are about the story.

Sure, some players are no-brainers: Babe Ruth, Ted Williams, Mike Schmidt. But for most of the players on this year's ballot, it was about the story.

Andre Dawson was the Hawk, a former MVP, one of the most admired men in baseball for withstanding 12 knee surgeries. This is part of his story, and it explains why he was finally elected: If he'd been a jerk who never needed knee surgery, I doubt he would have gotten in.

And that doesn't mean he isn't worthy. Dawson was, by definition, a borderline candidate (he was elected on his ninth try) and he needed something to get him over that border.

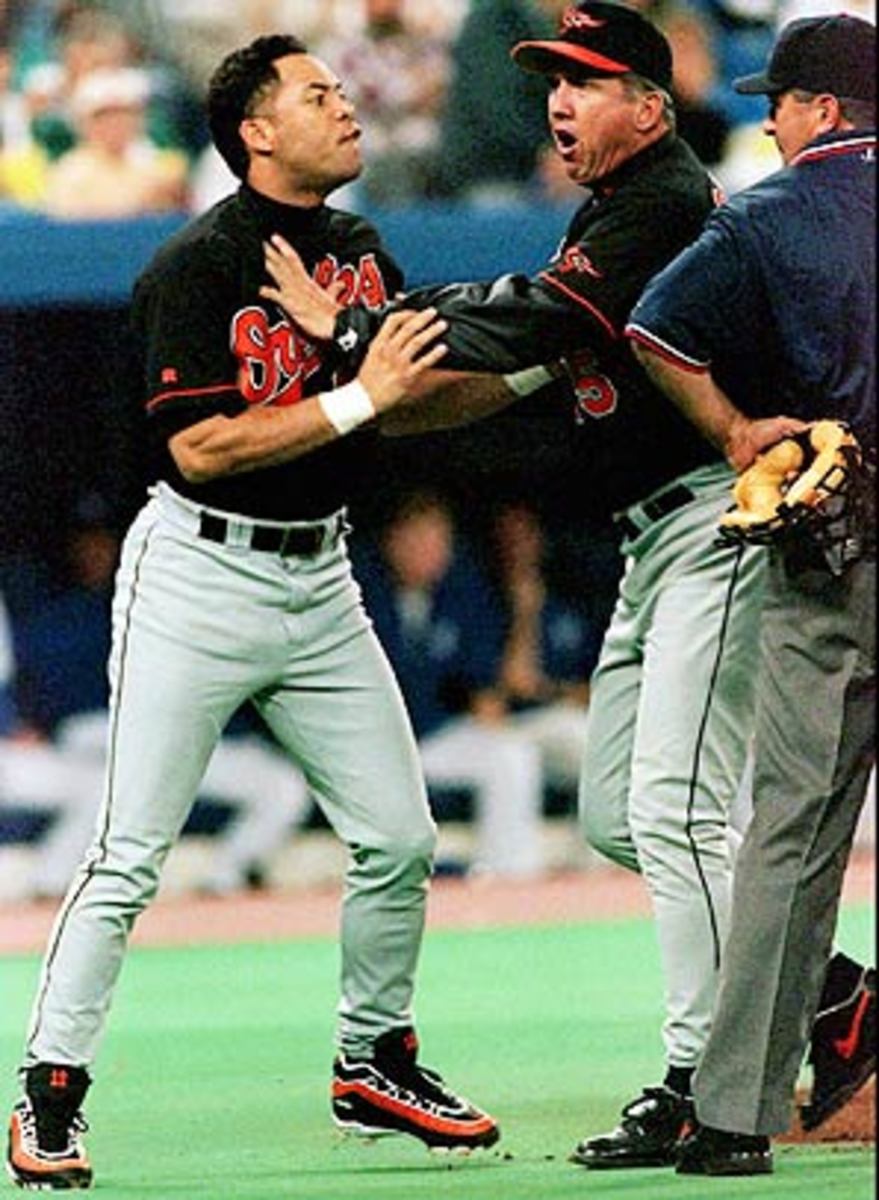

Roberto Alomar? He's the guy who spit on an ump. Delete those 10 seconds from his career, and Alomar would have gotten in. (As it is, he got 73.7 percent of the vote and will probably get elected next year.)

Let's change two things about Alomar's career. Neither is relevant to the kind of player he was when it really mattered. For one, let's imagine that he never spit at umpire John Hirschbeck in 1996. And second, let's imagine that he retired after the 2001 season, when he was 33.

Alomar would have finished with a .306 batting average, .378 on-base percentage and .455 slugging. Compare that to Hall of Famer Kirby Puckett's career: .318/.360/.477. Alomar had slightly more hits, and roughly the same number of home runs and RBIs, despite playing the middle infield, where defense is usually prized. And he was an exceptional second baseman.

It might seem silly to compare a second baseman to a centerfielder, especially since one of them got in the Hall nine years ago and the other one was on the ballot for the first time this year. But that is exactly what the voters have to do. Everybody gets thrown into the same pond, and writers have to decide which ones to fish out.

Puckett was a great player who won two World Series while playing his entire career with Minnesota. He was forced to retire shortly after his 35th birthday because of eye problems, even though he was still highly productive.

So Puckett got in rather easily even though he only hit 207 home runs, a low number for a Hall of Fame outfielder, and did not walk a whole lot. The voters clearly gave Puckett the benefit of the doubt -- he had been the smiling face of the Twins, and they assumed his numbers would have been better if he kept playing.

I'm not saying this is right or wrong; I loved watching Puckett and I don't mind him being in the Hall of Fame. I'm just saying that I don't think voters gave it a second thought. When Puckett appeared on the ballot, his story had already been written, and it included the words Hall of Famer.

And how do they decide? They look at the story. Jim Rice was the most feared hitter of his generation, or so we were told; I have no idea if that was true, but I am sure it played a role in his election last year.

When writers talk about how many MVP votes a player got, that's not a real stat: all they are doing is trying to quantify the story. An MVP vote, after all, is just somebody's opinion from a long time ago.

If Roberto Alomar had stayed healthy his final years and finished with 3,000 hits (he ended up with 2,724) would he have had a markedly better career? Probably not. But I can promise you he would have been elected this year.

If Edgar Martinez had played below-average defense at first base instead of spending most of his time as a designated hitter, would he have helped the Mariners win many more games? Probably not. But he would have received more than 36.2 percent of the vote.

I think a lot of voters didn't even consider Martinez because he rarely picked up a glove. The sentiment is understandable. But if they refuse to vote for any DH, then they are clinging to the story.

Like it or not, the DH has been part of baseball for more than 30 years. If there is one thing that every voter agrees on -- and it might be the only thing -- it's this: the tougher your defensive position, the lower the offensive threshold for making the Hall of Fame. In other words: Corner outfielders have to hit a lot more home runs to get to Cooperstown than shortstops do.

The DH should be treated for what it is: by far the easiest position, and therefore the one with the highest offensive threshold. Martinez was one of the five best hitters in baseball in his extended prime. I think that makes him a Hall of Famer.

When Bert Blyleven first appeared on the ballot, his story was simple: he'd been a very good pitcher for pretty bad teams who had piled up nice career numbers because he pitched for a long time. So he got only 17.5 percent of the vote. The next year, one line was added to his story: he'd already been on the ballot and hadn't done well, so voters were not inclined to waste a vote on him. His total dropped to 14.1 percent.

And that is when his story changed. Some people looked at Blyleven's numbers and realized that he had been much better in his prime than anybody gave him credit for, then or now. The fact that he had pitched for lousy teams suddenly became a plus for him, because those lousy teams kept him from winning games and postseason series and Cy Young awards.

Blyleven's story, today, is that he was woefully unappreciated in his era. You will see him as a Hall of Famer if you look at him from the right angle. He didn't get in Wednesday, but he did get 74.2 percent of the vote, just shy of the 75 percent required for induction. He'll be on the ballot two more years and should get in.

Jack Morris, meanwhile, had early momentum as the winningest pitcher of the '80s and a big-game horse. But that's also just a story, and that first part -- winningest pitcher of the '80s -- is just a combination of two poor stats: pitcher victories and an arbitrarily chosen time period. (And that is not to discredit Morris, who was a terrific pitcher, and absolutely a guy you wanted on the mound in a big game).

Want more examples? Suppose you are a general manager and you have a choice between two shortstops.

Player A will put up a career OPS+ of 87 (remember, 100 is the league average). He will never hit more than six home runs in a season and only bat .300 once. But he is a breathtaking defensive player.

Player B will put up a career OPS+ of 110. In his best six-year stretch, he will hit .303 with a .366 on-base-percentage and .467 slugging percentage, in a pitchers era, while playing Gold Glove-caliber defense.

Player A will finish with 100 more hits -- in more than 1,000 more at-bats and twice as many stolen bases. But Player B will dominate almost every other category.

If you are a general manager, you choose Player B, right? And that would mean choosing Alan Trammell over Ozzie Smith.

Yet when Smith and Trammell were eligible for the first time, in 2002, Ozzie got 92 percent of the vote and Trammell got 15.7 percent.

Why? Well, Smith is widely considered the best defensive shortstop ever, which arguably makes him the best defensive player ever, since shortstop is the most important defensive position on the field besides catcher. How can you have a Hall of Fame without the best defensive player ever?

I should probably point out here that I have not been in the Baseball Writers Association of America long enough to have a Hall of Fame vote; at this point, I'm merely an observer.

Like the rest of you, I have been told that Cooperstown does not house the Hall of Numbers or Hall of Very Good; it is the Hall of Fame. That, like so much about the process, sounds definitive but really isn't.

Is it for players who had fame, or players who should have had fame? I have no idea. I don't think it is possible to quantify the word fame. But every year, I watch people try.