As Golden Gloves loom, New York City boxing gyms in fight for life

They say boxing is dead.

But one glance inside the Morris Park Boxing Club last year -- amid the pulsating beats of hip-hop, the thwap-thwap of gloves on punching bags, the faint whistle of jump ropes, the smell of leather and sweat -- and you'd never have known it.

The gym, a longtime community fixture in the working-class Bronx neighborhood of Van Nest, had experienced a resurgence in popularity over the past few years. Owner Dex Pejcinovic brought on Aaron "Superman" Davis, the former world welterweight champion, as a full-time partner and trainer, and added new equipment and a newer paint job, bringing fresh life to the once-dilapidated space.

Thousands of young professional and amateur fighters had called the Morris Park gym home since it opened shop in 1977, among them homegrown world champions like Davis and Lou Del Valle, a one-time light heavyweight titleholder.

Everything changed three days before Christmas. An early-morning fire incinerated the gym and the two apartments above it. Fire department officials, unable to determine the cause of the blaze, thought faulty wiring might be to blame. Pejcinovic had liability insurance, but not fire coverage.

The flames consumed more than $50,000 in equipment -- the ring, gloves, heavy bags, memorabilia. "We took care of every kid who came in, even if they couldn't afford to pay for it," Davis said. "Boxing kept a lot of kids out of trouble."

The fire displaced the club's 150 members at the most inopportune time: on the eve of the Golden Gloves, the region's most popular amateur tournament, which began in January and concludes at Madison Square Garden with the finals on Thursday and Friday. It's a contest in which countless aspiring New York City fighters seek fortune and glory and, at the least, temporary escape from the streets.

Moreover, the destruction of Morris Park Boxing Club meant one less place for area pugilists to train -- just the latest hard knock in the long, slow decline of the New York City boxing gym.

* * *

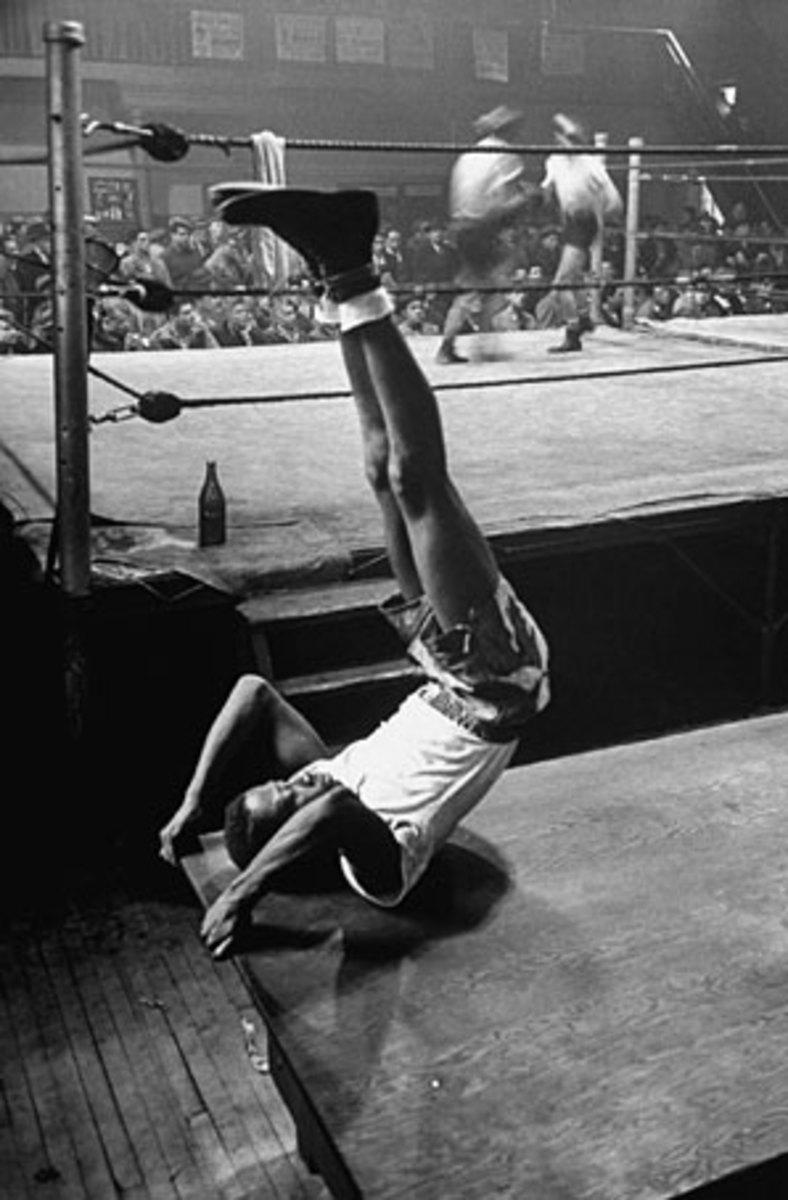

Boxing -- the sweet science of bruising -- once commanded America's national consciousness like no other public spectacle. Prizefighting was the nation's preeminent sport during the first half of the 20th Century and New York City was its commercial and spiritual epicenter, home to meccas like Madison Square Garden and Yankee Stadium, the place where the New York State Athletic Commission determined matchups and acted as the sport's de facto governing body.

It's also where scribes like A.J. Liebling of The New Yorker spun legends and made folk heroes out of such champions as Joe Louis, Rocky Marciano and Sugar Ray Robinson.

No more. Just 20 years ago, more than 150 gyms were scattered throughout the five boroughs. Today there are fewer than 10.

Read the classic literature on what Mike Tyson eloquently called the "hurt business" -- Joyce Carol Oates' "On Boxing," A.J. Liebling's "The Sweet Science," W.C. Heinz's "The Professional" -- and the pages come alive with smoke-filled spaces where fighters trained, admirers gawked, managers machinated, old men dreamed dreams and young men saw visions. Gramercy Gym on East 14th Street near Union Square. Grupp's Gym uptown in Harlem. The famous Stillman's Gym, where the brilliant Benny Leonard trained, just four blocks north of the old Madison Square Garden.

The corpses remain visible throughout the city. That Gramercy club -- owned by Cus D'Amato, trainer of world champions Floyd Patterson, Jose Torres and Tyson -- has become a P.C. Richards store. Grupp's is a Food Bank For New York City; where needy, downtrodden citizens once gathered to fight, they now line up for a hot meal. Google the names and the old addresses of the others and you'll find a Jamba Juice or an American Apparel.

Bruce Silverglade, owner of Gleason's Gym, estimates just 50 men in New York earn a full-time living as boxers.

Why the precipitous drop over the past two decades? It's no secret that boxing is a waning enterprise. Some stock explanations: With no viable American contenders at heavyweight -- always the sport's prestige division -- mainstream interest in the U.S. has nose-dived. Where the three television networks broadcast major bouts as recently as 20 years ago, significant fights now air exclusively on HBO, Showtime and other pay cable networks. Pay-per-view costs for marquee events have climbed as high as $59.95, pricing out the casual fan. The reduction in outlets makes a promoter's job more difficult and saps the demand for fighters, who today earn between $800 to $1,000 for a four-round bout. (And that's before the 10-percent cut to the trainer and up to a third for the manager).

Once the sport's undisputed mecca, New York has been supplanted by Las Vegas, where the casinos offer free venues and hotel rooms to just about everyone involved with a promotion. Even when promoters desperately want to stage a major fight in New York, they find it simply not feasible.

"When the casinos came in total vogue, the fights left New York," Silverglade says. "Take Madison Square Garden: If you use the theater, it going to cost you $125,000 just to open the door -- just to turn the key to get in there -- and you don't get food or concessions. The big arena is well over $250,000 just to open the door. So where do you want to fight? Do you want to go fight in New York where you have to pay the Garden $250,000 plus put up all your fighters? Or do you want to go to Las Vegas where they're going to pay you [a site fee] to have the fight there and they'll give you free room and board?"

Bob Arum, founder and CEO of Top Rank, one of boxing's largest promotion companies, wanted a Super Bowl-type stage for this year's proposed megafight between Manny Pacquiao and Floyd Mayweather Jr. The company briefly considered the new Yankee Stadium, across the street from where Louis and Marciano fought before crowds of 80,000 during boxing's golden age, but Arum was forced to nix the idea. "You cannot do a major fight in a city like New York because of the insane taxes that they have here," Arum told SI.com in January. "There is a state tax, a city tax and an independent contractor tax. You put them all together and it's like 15 percent. Let's assume the purses will aggregate $80 million. Fifteen percent is $12 million dollars. That's like giving away the whole gate to the state. That's crazy."

By comparison, Nevada raised its boxing commission tax from 4 to 6 percent in March (effective July 1). But there's no city tax and the state tax is just 4 percent. In the case of Pacquiao-Mayweather, Vegas offers a savings of nearly $5 million over New York.

The higher cost of living in New York has also undercut the local talent pool. Many boxers train in the South, where life is cheaper, or in Las Vegas or along the Gulf Coast where there are more casinos and opportunities to fight.

Some factors are old news, like the decades of corruption in the sport. In boxing's heyday, old-timers often bemoan, there were eight world champions, from flyweight to heavyweight, and everyone knew who they were. But the sport's lack of a central authority has created an alphabet soup with multiple champions, super champions, interim champions, regular champions and champions emeritus -- in 17 divisions instead of eight. Other sports have commissioners to set the rules and standards -- but not boxing, where the athletes are individual contractors and the myriad sanctioning bodies that determine these "champions" answer to no one.

Most of all, fewer poor youngsters are turning to boxing when basketball is a much more attractive, more lucrative and safer alternative. Boxing gyms have struggled to keep their doors open as business declines, while rents escalate and gentrification encroaches.

"I see boxing today as doing what the stock market did just before the crash," says Gumersindo Vidot, the Philadelphia representative for the Retired Boxers Foundation. "Everybody is getting all their money out of it. Before the market crashed, the stock brokers knew what was going on. They even have emails and voice recordings of these guys saying, 'Get your money out now because this is going to hit the fan.'

"I see that boxing is doing the same thing. I feel it's fading to a point where these guys are just pimping. You've got the [Oscar] De La Hoya, Bob Arum, they're only using the same damn guys all the time. Whatever happened to these young guys who came from the street? They don't have any opportunities anymore. You get into boxing now, forget it. You've got as much of a chance as getting in the NBA."

Vidot, who says boxing saved his life as a youngster in the South Bronx, believes a grassroots approach -- an appeal to the common fan -- is the only way for the sport to become a marketable enterprise in the long term.

"You want to bring boxing back? You have to bring that kid from the community and put him on TV. Let him fight," Vidot said. "They're just pimping these big fights out there and it's a shame, because they know it's fading so much and MMA is taking over, and they're just saying, 'Let's make as much as we can out of it and then the hell with them.'"

* * *

Not long after Joseph Medill Patterson founded the New York Daily News in 1919, the paper began sponsoring a variety of sporting events over the next decade in an effort to boost its circulation. By far the most popular was the Silver Skates Derby. The annual speed-skating tournament -- conceived in 1922, early in the breakout decade for American sports -- captured the collective imagination of a sports-mad city and proved an unequivocal success for the infant tabloid. So when sports editor and amateur boxing enthusiast Paul Gallico pitched Patterson the idea of a city-wide boxing tournament, it was an easy sell. Gallico even had a tournament name picked out -- the Golden Gloves -- a nod to the event that inspired it.

"I am bugs enough about amateur boxers, their romance and their opportunities," wrote Gallico in the first of several columns promoting the inaugural event, "to think perhaps the tournament of the Golden Gloves will unearth some unknown with a bland and modest smile and a kick like a mule, who will blast through the national championships in Boston with Golden Gloves dangling from his belt. He will have beaten the best in the metro area, and with Golden Gloves as a talisman well, who can tell? The opportunity will be there."

Opportunity was the essence of the Golden Gloves, and still is. Before you're paid to fight as a professional, you learn the trade in the amateur ranks. If you can prove yourself there, you can make a living. But whether the lure is professional glory, that chain with 10-carat gold miniature gloves or those precious column inches in the Daily News, participants see a chance to turn their lives around.

Today, the Golden Gloves is the world's largest and longest-running boxing tournament besides the Olympics.

Almost as interesting as the matches themselves are the unique backstories fighters bring into the ring. Narjis Kabiri is a senior at West Point who'd never boxed a round in her life before her opening fight at this year's Gloves, when she wiped the floor with a girl from John's Gym. (Kibiri will deploy with the 82nd Airborne next year.) Kevin Rooney, Jr., son of the famous boxing trainer who helped guide the career of a young Mike Tyson, promised to enter the Gloves if his dad stopped drinking; Rooney, Sr., did, but Junior lost on points in the quarterfinals. Tiffany Chen grew up in martial arts -- her father is an instructor at a place near Manhattan's Mendez Boxing Club -- but recently turned to boxing and needed just one punch to beat her quarterfinal opponent from Gleason's.

You've got some of the most naturally gifted athletes you've ever seen who can't be bothered to hit the heavy bag or do the road work. And you've got modest-looking specimens who overachieve spectacularly thanks to effort and dedication. You've got guys who are using the Gloves as a stepping stone for the professional ranks -- they know they'll get their names in the Daily News and appear on the MSG network -- and they see the tournament as a platform to promote themselves. And you get other guys who call up the office and say, "I've never fought before. What do I have to go buy for tonight?"*

*This actually happened once this year; the fighter was subsequently taken to the hospital for a precautionary CAT scan.

* * *

From the outside, it doesn't appear so bad. The awning looks brand new, and the red, white and blue mural on the outer facade -- with MORRIS PARK BOXING CLUB in block letters -- appears as fresh as the day it was painted less than a year ago. Aside from the padlock on the door and the dumpster half-filled with debris, there's little to suggest the destruction within.

But inside, shafts of sunlight peeking through the punctured roof create a charcoal tableau. The two-room gym, once bustling with activity seven days a week, is empty save for the charred remains of scattered equipment -- a glove here, a training belt there. No sign of the handpainted message that once stared down on the space: IT'S BETTER TO SWEAT IN THE GYM THAN TO BLEED IN THE STREETS.

Cus D'Amato once described a knockout as a failure of communication between mind and body. A fighter with an authentic desire to win cannot be knocked out if he sees the punch coming, D'Amato insisted.

Davis didn't enjoy the luxury of foresight. He was asleep on the morning of Dec. 23 in his nearby apartment when the phone rang.

"I got a call and was told I needed to come right down to the gym immediately," Davis recalls. "I jumped into cab and couldn't believe what I saw when I got there."

The owners of the Morris Park gym had no time for anguish, not with the Golden Gloves less than a month away. Hours after the blaze swallowed their business, Davis made temporary plans with John's Gym -- a 10-minute drive away in Melrose, nine stops downtown on the 2 train. Known for training such accomplished West African fighters as Joshua Clottey and Joseph "King Kong" Agbeko, John's is a modest space on the second floor of an old post office. Owner Gjin Gjini lent a sympathetic ear and offered free one-month memberships to the 11 Morris Park fighters -- nine men and two women -- in training for the Golden Gloves.

Many of them -- like Rashid Wright, Mike Cardenas, Jose Robles and Donald Ngwang -- are students aged 17 to 25 according to their registration with the Daily News. Keith Brown, was a first-year entrant in the novice division, is a 34-year-old elementary school teacher of Albanian descent. Middleweight Rodney Carter Sr., 28, works as a personal trainer. Victor Morales, the heaviest team member at 201 pounds, is a U.S. Navy veteran. Frankie Garriga, a 21-year-old Bronx native preparing to fight in the Gloves for a fifth time, captured the 119-pound novice championship in 2008. Last year, Garriga was fired from his security-guard job just two weeks before the competition for missing work to train. He went all the way to the finals of the 125-pound open division before losing by decision in the final.

Members of John's Gym and the Morris Park club trained side by side -- a strange but necessary marriage, and an example of the boxing community coming together in a crisis. If there's been any animosity, it's been between the trainers. Fighters from both gyms have mentioned arguments boiling over due to the cramped space.

Jose Torres once said the machismo of boxing is a condition of poverty. And true, many of Morris Park Boxing Club's students come from lower-income neighborhoods in the Bronx. "It's hardly a secret that boxing does not get its enlistees from the debutante lines at the local country club; nor the law offices or accounting firms down on Wall Street," boxing historian Bert Sugar wrote. "Instead, it draws its recruits from the tenements, the ghettos, the projects, the barrios, the nabes, hardscrabble places offering little presence and even less of a future."

If anyone knows the redemptive value of the sweet science, it's Pat Russo. A retired narcotics officer who spent 22 years at the 72nd Precinct in Sunset Park, Russo got into the sport as a rookie in 1985, when he responded to a poster looking for officers to join the NYPD boxing team. At a basement gym in Starrett City, a lifelong passion was discovered.

"It taught me discipline and it taught me confidence," Russo said. "As a kid I was always shy and I hated to get up in front of a class and speak. It helped in that sense. It gave me the confidence that you can handle yourself if you can prepare. And that's what boxing is: Boxing teaches kids work ethic."

The NYPD deemed Sunset Park the model precinct for community policing during Russo's first several years in the neighborhood, and officers were encouraged to think of outside-the-box ways to solve local issues. For Russo, the solution was obvious.

"Some of the main problems that were affecting the community were drugs, gangs and a lack of things for the kids to do. I said I wanted to start a boxing program," Russo said. "We could give kids an alternative to the street."

Russo learned about a ring in an abandoned building on Snyder Avenue that was going to be torn down with the ring still in it. He got permission from the Department of Parks and Recreation to start up a free program in the actual parkhouse building in Sunset Park.

For 22 years, Russo's Sunset Park Boxing Club kept at-risk kids off the street and taught them to exert their aggression in a positive way -- and it didn't cost the city a nickel. ("They gave us our own space," he allows, "but it was an empty space!") Russo says the sport was seen not just as an alternative to gangs, but as a police recruiting tool.

"You think it's cliche," Russo says, "but the competition for these kids between the Bloods, the Crips, the Latin Kings, it's out there. And if we can get a kid walking down the street wearing a Sunset Park Boxing Club sweatshirt, make him feel like he's part of something that he's going to be able to use, they can walk the streets. They can be proud in a positive way. They're doing something good. They're eating right. They're not doing drugs. If you look at the Golden Gloves -- less than 1 percent of the kids test positive for drugs. 'Cause you can't. You can't drink alcohol and you can't do drugs if you want to be successful at this sport."

But when the city received a $500,000 grant from the Department of Education in 2007 to start an after-school workshop in the space that Russo's program called home, the Sunset Park Boxing Club was forced off the premises -- and nearly 60 youngsters found themselves without a place to train.

Within months, a benefactor in nearby Red Hook offered an empty space if Russo wanted to move one neighborhood over. Just like that, the Sunset Park Boxing Club was rebranded the Red Hook Boxing Club. But it wasn't long before a lease conflict forced Russo's charges to the street again.

"There's an obvious bias against boxing by the elitists that see it as a brutal, barbaric sport," Russo says. "They've never done it before. They have no idea the whole concept of it. They just don't get it."

What might have been a fatal blow came when Police Athletic League executive director Felix Urrutia, citing a "paradigm change," chose to terminate the long-running PAL boxing program on the eve of the 2009 Golden Gloves. Urrutia's initial compromise was a fitness program with no competitive boxing -- no physical contact -- but Russo knew "that wasn't going to attract that kids that we needed to attract."

Instead, Russo and friends held fundraisers and registered about 50 kids for the tournament, paying the admissions and club fees for the fighters and certification fees for the coaches. They switched everyone's affiliations to NYC Cops & Kids, an umbrella team for all the kids whose PAL programs went under, so they wouldn't need to enter the Gloves "unattached."

The response of Russo's refugees was impressive: At last year's Golden Gloves, NYC Cops & Kids captured the prestigious team trophy -- an honor they hope to defend Thursday and Friday at Madison Square Garden.

"Boxing attracts those at-risk kids that are on the borderline, who can go either way into gangs or drugs or other criminal activity," Russo says. "PAL boxing has been around since 1935. It has a longstanding history in New York as far as providing kids a place to go. It was established by police officers that were just looking for a positive outlet for kids. I couldn't let one person's opinion of boxing just destroy all that history."

* * *

It's opening night of the 83rd annual tournament at B.B. King Blues Club in Times Square and the packed house is abuzz. Officials in black T-shirts make final adjustments to the ring, set in a two-tiered, horseshoe-shaped seating area. Sports luminaries like Giants running back Brandon Jacobs and former Knicks guard John Starks occupy VIP booths near ringside. Yuri Foreman and Paulie Malignaggi, two of the city's finest professional fighters, hold court with their entourages and snap photos with any admirer who works up the nerve to approach.

Tonight is only the first of 33 different cards over the next eight weeks, leading to the finals at Madison Square Garden in March -- but it's certainly the most glamorous fixture on the docket. Other preliminary rounds often take place before crowds of various sizes at high schools, church halls, rec centers, Masonic temples and American Legion posts across the five boroughs.

Six fights in the 141-pound open division comprise tonight's card, but there's only one fighter everyone in the house wants to see: four-time Golden Gloves champion Shemuel Pagan. He's passed on the opportunity to turn pro, and the chance to collect a paycheck for his sacrifice, for a shot at history. Pagan, who's 21, wants to match the all-time record of five consecutive Golden Gloves titles set by Mark Breland, the Brooklyn native who went 21-0 with 14 knockouts in the competition between 1980 and '84 -- and capped that run with a gold medal at the Los Angeles Olympics. (Breland, not incidentally, is ringside tonight.)

Fights in the open division consist of three 3-minute rounds -- except for three 2-minute rounds for the novice division and four 2-minute rounds for women -- and the boxers wear padded headgear. Amateur rules place a premium on scoring points based on the volume of clean punches landed, as opposed to sheer physical force.

An eerie quiet falls when the bell rings for the first fight, enhancing the sound of footsteps and leather against flesh. The wiry teenager in the blue corner is Carlos Teron from Russo's NYC Cops & Kids, younger brother of Jorge "The Truth" Teron, a three-time Golden Gloves champion and one of the tournament's recent success stories.

Three more fights and it's time for the main attraction: Pagan. Those who've spent most of the night watching by the bar come to life and stake whatever spaces with clear sightlines remain. The veteran is easily recognized from afar, thanks to the long frizzy ponytail hanging from the rear of his gold headgear. A Hebrew Israelite, Pagan has long associated his signature hairstyle with strength, in keeping with the Old Testament hero Samson.

A lifelong resident of Brooklyn's Borough Park, Pagan goes by the nickname "The Problem" -- and that's exactly what he presents for tonight's opponent, Tyrell White from John's Gym. Pagan's devastating combination of power, speed and accuracy sends White to the canvas within the first minute of the first round, with a quick, pulverizing right hook that seems to appear from the ether. The second knockdown comes just moments later, after another devastating combination of body shots. The ref stops the action just 87 seconds into the first round.

* * *

Despite the excitement of the Golden Gloves, even New York's venerable gyms are either struggling or adapting to survive.

Gleason's is New York's most famous gym and the oldest active boxing gym in America. Founded in 1937 in the Bronx, now in its third home on the second floor of a DUMBO industrial building, it's probably the best-known gym in the world.

The interior is familiar, unchanged by time: boxers skipping rope, shadowboxing, sparring in the four practice rings, slugging away at heavy bags along the walls. Many pro fighters still train here, among them junior middleweight champion Yuri Foreman, former welterweight champion Zab Judah and up-and-coming heavyweight prospect Tor Hamer -- following in the footsteps of Jake LaMotta, Floyd Patterson and a young Cassius Clay. The inscription near the entrance of the 14,000-square-foot space -- less stark than its Morris Park counterpart but no less inspirational -- comes from Virgil: "Now, whoever has courage and a strong collected spirit in his breast, let him come forward, lace up the gloves and put up his hands."

Even as powerful a brand as Gleason's hasn't been immune to the citywide decline. Complicating matters is the sharp rise in boxing insurance, for which owner Bruce Silverglade pays around $25,000 per year. ("[It] has gone up in proportion and percentage more than any other expense that I have," Silverglade says, "and without any incidents.") While there's always a spike in membership around New Year's Day -- a joint consequence of New Year's resolutions and Golden Gloves season -- Silverglade says the gym has suffered a 6 percent drop in membership over the past two years.

After graduating from Gettysburg College in 1968 with a degree in economics, Silverglade entered the Sears Roebuck management program and ran one of the company's stores on Long Island, but worked in amateur boxing as a volunteer. After serving as the national chairman for the Junior Olympics, Silverglade became president of amateur boxing in New York City. One day at Gleason's while making the rounds, the owner mentioned that he was looking for a partner.

The very next day, Silverglade went back to Sears and resigned.

"I couldn't wait," recalls Silverglade, who bought a 50-percent share of Gleason's after cashing in his profit sharing from 16 years with Sears. "When I had the opportunity to change my hobby into my lifelong dream -- having a good time and being involved with Gleason's, which was such a big name in boxing -- I just couldn't resist it."

Silverglade says there's been a radical transformation in DUMBO since he bought Gleason's, "from a very, very nasty slum area to probably one of the wealthiest neighborhoods in all of Manhattan."

Business was steady for years, but just as a fighter must adjust tactics on the fly against a stubborn opponent, most of New York City's hardcore boxing gyms have had to adapt to survive.

One solution for a brand as recognizable as Gleason's is alternate revenue streams. Silverglade says the gym has hosted location shoots for TV shows and 26 feature films -- including four Academy Award winners -- as well as fashion shoots, corporate parties, bar mitzvahs and weddings.

"If somebody in New York says boxing, they say, 'Oh, Gleason's Gym,'" Silverglade says. "It's synonymous. It's like Kleenex and tissue paper."

Many gyms, like Gleason's and the Church Street Boxing Gym, now primarily cater not to aspiring fighters but to white-collar clients, who may want a rigorous workout, or a way to tap something carnal within, but aren't looking to boxing for a livelihood. Silverglade estimates that 65 percent of Gleason's members are businesspeople, the rest being professional or amateur boxers.

"The only thing that has allowed me to survive is the fact that we draw from the neighborhood," Silverglade says. "I have a pretty good monopoly on boxing and boxers from around the world come here. But the rents have soared in this area from when it was a slum to what it is today. And the increase in membership of businessmen and women is what allows me to survive."

But during this recent economic crunch, the loss of that business clientele has made a gloomy situation worse.

"I told everybody for years we were recession-proof, because we never had a bother in the '80s when [Black Monday] happened," Silverglade said. "What happened to Gleason's is my membership was going from 99 percent fighters to 35 percent fighters. I opened the door to all these business guys, which was great, income was coming. But when the recession came, I was affected."

Of Gleason's 930 registered members, more than 300 are now women, often hoping to learn self-defense. (It's come a long way from when Silverglade became part-owner in 1981, when women weren't even allowed to join.) Gleason's managers have made the environment very friendly to newcomers, and many gyms now openly market themselves to women.

Some gyms have made the metamorphosis from hard-core boxing gyms into fitness centers. Others have even begun to offer classes in mixed martial arts, a business move that would have been anathema to boxing traditionalists a few years ago.

Take the Church Street gym on Park Place, two-and-a-half blocks from Ground Zero. Owner Justin Blair began organizing Friday Night Fights cards for his mostly white-collar customers beginning in 1997, when the gym opened its doors. The buzz around the events quickly outgrew the small gym, and Blair needed to seek larger spaces like the Church of St. Paul the Apostle on the Upper West Side. Today, many of the cards are a mix of boxing and muay thai, a form of Thai kickboxing. While the events once offered boxing exclusively, the rise in popularity of mixed martial arts has led Church Street to accommodate the public demand. Such flexible entrepreneurship is familiar to the owner of Gleason's.

"I go out and try to solicit as much as I can to bring money in and keep the doors open," Silverglade said, "because once I get through bragging about how well-known Gleason's is, I'm a small business owner in New York. And I have all the problems of insurance and rent and everything else that all small businesses have. You can't just sit back, you have to go out there and hustle and make things happen."

* * *

Aaron Davis thought about opening his own gym even before the fire that consumed the Morris Park Boxing Club, but the events of the past few months helped fast-track those plans.

"I knew I needed a bigger spot," he says, while pacing through the first-floor workout room of the Aaron Davis Boxing Gym. "There's a train station right here and tons of buses come through. Easy access for everyone and it's close to Morris Park."

Davis, 42, captured a Golden Gloves title in 1986. Four years later, the Bronx native knocked out Mark Breland for the WBA world welterweight championship. He retired in 2002 with a professional record of 49-6, and has since devoted himself to bringing along up-and-coming boxers in the Bronx.

The official grand opening of Davis' gym isn't until April 1. But several young fighters, including many who he guided at Morris Park, have already begun training in the unfinished facility.

Davis has spent 15 hours a day refurbishing the old warehouse building in the shadow of the elevated train tracks along Westchester Avenue since purchasing it last month. Ten days before doors open, the renovations are ahead of schedule. The accessible location, one block from the Westchester Square stop and Herbert H. Lehman High School, is just one reason for Davis' optimism.

Today, the scent of fresh paint -- black for the floor, white for the wall -- fills the space. In the ring at the back of the room, Luis Rosato (a three-time Golden Gloves champion in the early '90s) works the pads with a teenage protégé. With contagious enthusiasm, Davis talks about the gym that bears his name.

"All experienced trainers," Davis insists. "Anyone can walk in the door, throw a towel on their back and call themselves a trainer. Boxing is the only sport where a guy can say 'do this' and 'do that' when they've never done it themselves. You can't tell someone how to get out of a situation if you've never been in that situation yourself."

There's already one ring, four heavy bags and a couple of speed bags on the first of two 3,000-square-foot floors, with a second ring and more bags to come. Downstairs is another training area for the elliptical machines, light weights and treadmills. Davis even invested $34,000 in a central air system, a rare luxury for a boxing gym.

Davis talks about the future with the gusto most boxing folks reserve for the past. To listen to the former champ, you'd have no idea about the pessimism that surrounds the sport as a profitable enterprise. It's not that he's unaware of boxing's ailments. He hates that fighters often have no choice but to go with a local promoter. He hates that promoters shop out of the tri-state area for "opponents" to inflate their prospects' records instead of feeding some of the precious few fighting opportunities to local boxers. But rather than lament the state of boxing in New York City, Davis is taking proactive steps toward rebuilding the sport across the five boroughs. Beyond the gym, he's hoping to buy the larger warehouse adjacent to the gym and convert it into a venue.

"There's a building right next door we're looking to get -- it holds 2,500 -- for amateur and pro shows," Davis says. "We're going to be doing a whole lot of things, including some promotions."

When the pizza comes, Davis grabs a twenty from his sock and offers a slice to everyone else first. Altogether, he says he's invested $200,000 into the gym, which he sees as a worthy investment in the neighborhood. He won't make it back overnight -- the $55 monthly dues for adults are modest compared to other gyms, and he'll never turn away a kid whose parents can't afford to pay for training -- but the return in goodwill is beyond measure. When Aaron Davis' gym opens, many of the Morris Park fighters who have taken up temporary residency at John's Gym will follow.

"You're going to see a lot of Golden Gloves champions coming out of this gym in the next couple years," Davis says, smiling at the vision of it. "And in another five to eight years, you're going to see world champions."

* * *

There are a million reasons why the sweet science should no longer exist, why there's truth to the boxing-is-dying column that's become a mainstay for sports pundits nationwide. At the same time, boxing has always been a sport on the precipice of extinction -- and it's always managed to endure, from the ancient Greeks through the English bare-knuckle fights of the 18th Century through today.

The undercurrents of race and class are obvious: For years, boxing has been credited with uplifting impoverished youths, yet it's constantly under attack from middle-class reformers like the American Medical Association. ("One of the standard arguments for not abolishing boxing," Joyce Carol Oates wrote, "is in fact that it provides and outlet for the rage of disenfranchised youths, mainly black or Hispanic, who can make lives for themselves by fighting one another instead of fighting society.") Russo, fed up with the out-of-touch bureaucracy that disregarded the positive impact of the PAL boxing program, says attacks on boxing have always been politically safe.

"The kids that we attract have nothing and their parents are not voters," Russo says. "The coaches become their mentors and their parents and guide them. We make them take all the civil service tests. Now that's not all of them, but it's a majority of the kids -- the average kid that you want to get that's going to join the Latin Kings or the Bloods."

For men like Russo and Davis, boxing is less a sport and more a mission. They're firm believers in the regenerative properties of the discipline. And their tales provide good reason.

This week, Russo opened the Flatbush Gardens Boxing Club, a permanent home for his itinerant boxing program. High-profile donors, among them Dustin Hoffman and Teddy Atlas, have helped make Russo's dream a reality. Atlas and New York City police commissioner Raymond Kelly spoke at Wednesday's ribbon-cutting ceremony.

It's an emotional victory, but there's no time to celebrate: Starting tonight, nine of Russo's NYC Cops & Kids fighters -- four from Staten Island and five from the Bronx -- will try for the club's second consecutive team trophy in the Golden Gloves finals at Madison Square Garden.

And when that's over, you can bet Russo will be on the hunt for the next wave of recruits.

"Junior high school," he says, "that's when you have to get to them."