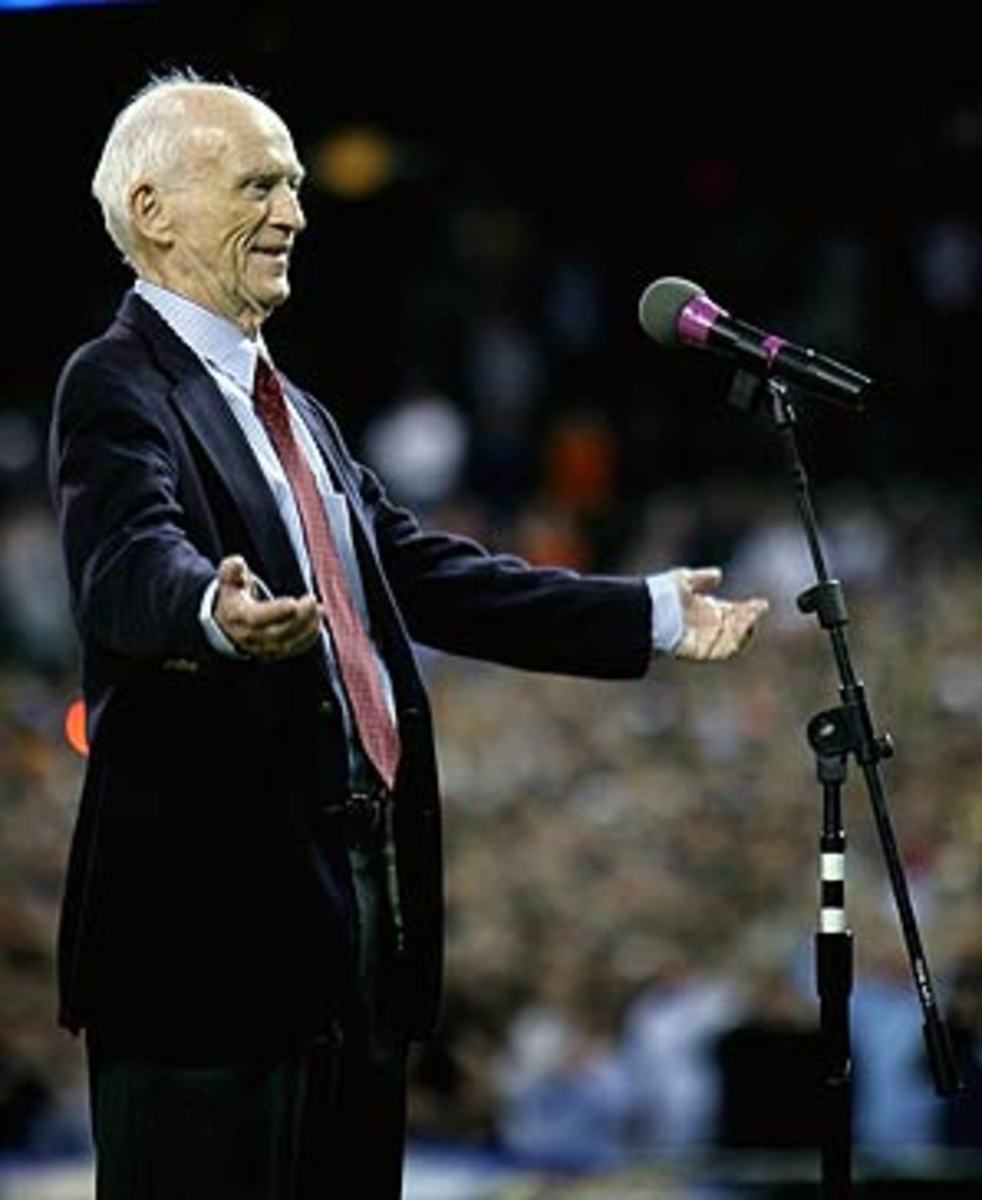

For more than 50 years, Harwell was what fans wanted: a friend

BB for baseball.

Peach for Georgia.

That was Ernie Harwell.

The emails were never long, never more than a sentence or two. They were always happy thoughts: Thank you for writing this.... I love triples in the gap too.... I was thinking about Buck O'Neil today... Is there anything more fun than a promising new rookie... What a wonderful gift you have... All these years and hitters still chase the high fastball, don't they?... I still love the sounds of those fountains in Kansas City, don't you?

How does a man live 92 years without losing his innocence? How does a man announce baseball games for more than a half century and still appreciate triples in the gap and still hear the whisper of the fountains? How is it that a man who spends his whole life bringing joy to other people spends his days worrying that he has not said "Thank you" enough?

These are the wonders of Ernie Harwell. It's a funny thing about broadcasting baseball games: Some people are good at it and some people are not as good -- you know, as far as that technical stuff goes -- but unlike just about any other walk of life, quality is beside the point when it comes to our hometown baseball announcers. Yes, we want pilots who are proficient and doctors who are skillful and bankers who are methodical and dentists who remember that we need to rinse. We want columnists who are interesting, and actors who help us believe, and secretaries who are efficient, and coaches who win. We want announcers in football and basketball and hockey and other sports to keep up with the action and tell us what we want and need to know.

But with our hometown baseball announcer, we want a friend. We will get used to his quirks. We will grow accustomed to his voice. We will not love everything about them. We may occasionally shout, "Come on, give us the score already!" or "Not that story again!" But that's all in the rhythm of the games, 162 of them every year, 810 of them every five years, 2,106 of them every 13 years, 4,050 of them every 25 years, and so on, and so on, the long march, thousands of home runs, thousands of check swings, tens of thousands of strikeouts, and just enough tailor-made double plays to keep our team in the game.

And you listen -- some listen religiously, some when they happen to be in the car, some reaching out from a great distance for a little bit of home, some just to pass the time -- and if the announcer seems real then, without even thinking about it, his voice becomes a part of your life. The style hardly matters. Go crazy, St. Louis. Have a Bud on Rush Street, Chicago. It's a beautiful day for baseball in Cleveland. Two and two to Harvey Kuenn in Los Angeles. In Seattle, it will fly away. In the Bronx, theeeeee Yankees win again. The ol' left-hander is rounding third and heading for home in Cincinnati. The ball is outta here in Philadelphia. And so long everybody in Atlanta.

Ernie Harwell had his routines too. You don't announce baseball games for 55 years without building routines. He would often shout out the hometown of the person who caught a foul ball -- Ypsilanti, Grosse Pointe, Saginaw, Lansing -- and a young Bob Costas, sitting in his father's car on Long Island and listening to Tigers' game, would always wonder how Ernie knew. Ernie would sometimes fit in a verse of poetry between pitches -- Ernie loved words. He loved how words played off each other, how one word sounded following another. He began every season with his reading from the Song of Solomon: "For lo, the winter is past; the rain is over and gone; the flowers appear on the earth; the time of singing of birds is come; and the voice of the turtle is heard in our land." People would send him turtle plushy toys now and again.

But it wasn't the poetry, and it wasn't tradition, and it wasn't the turtles, and it wasn't the foul ball hometowns that made Ernie Harwell beloved. It wasn't his memorable voice, dripping with Georgia all of his life -- The Tigers becoming the Tiguhs, and Al Kaline transforming into Aelll Kay-lahn. It wasn't the way he would wrap up double plays by announcing that the home team had gotten two for the price of one or the simple hope that would fill his voice in the late innings with the Tigers down by two runs.

No... it was Ernie himself. He was always there, night after night, day after day, missing only two games in his long broadcasting career -- one for his brother's funeral, the other for getting his lifetime award from the Hall of Fame. And he wasn't just present -- he was always THERE, full of life, full of optimism, full of faith, full of wonder.

The last email I got from bbpeach80 was a few weeks ago; it was an invitation to call. I had written him an email expressing how proud I was to know him, even a little bit, and how lucky I was to call him a friend. Of course, everyone who ever listened to Ernie Harwell called him a friend. "It isn't me that people love," he said to me once, "It's baseball." But, of course, it wasn't true. People loved him.

And so I told him how much he meant to me. You only get to meet and talk with so many beautiful people in this life. I've been lucky. I've known more than my share. He wrote back and thanked me -- I wonder if any person who ever lived said "Thank you" more than Ernie Harwell -- and said that I was welcome to call if the mood would ever strike me. He enclosed his telephone number like he had a few times before. I never did call; I knew so many people were calling. I had said what I wanted to say. I had taken up too much of his time.

But more than once, I would go on the Internet and listen to his beautiful definition of baseball.

The only race that matters is the race to the bag ...

Baseball is a rookie, his experience no bigger than the lump in his throat ...

A tired old man of 35 hoping that those aching muscles can pull him through another sweltering August ...

Why the fairy tale of Willie Mays making a brilliant World Series catch ...

Baseball is cigar smoke, hot-roasted peanuts, Ladies Day, "down in front." ...

In the videos I found, he inevitably would leave out my favorite part. He was too modest to say it again. Baseball is a tongue-tied kid from Georgia growing up to be an announcer and praising the Lord for showing him the way to Cooperstown. Ernie Harwell knew he was dying. Last July, the doctors told him he had only a few months left to live. He made it to see another start of another baseball season. He heard the voice of the turtles once more. He had seen another triple hit into the gap. He died Tuesday, at age 92.

"I've lived a wonderful life," he said. He did. He lived a wonderful life. But what made him Ernie Harwell was that he never failed to remember. Our friend Buck O'Neil used to say that he went to the ballpark hoping one more time to hear that thunderous crack of the bat, that unusual sound he had only heard three times in his life, once for Babe Ruth, once for Josh Gibson and once for Bo Jackson. Ernie Harwell used to say that he went to the ballpark with the expectation that he would see something he had never seen before. And day after day, he saw that something.

Why? Because he was looking for it.