Racial overtones surrounding UFC 114 unnecessary, inappropriate

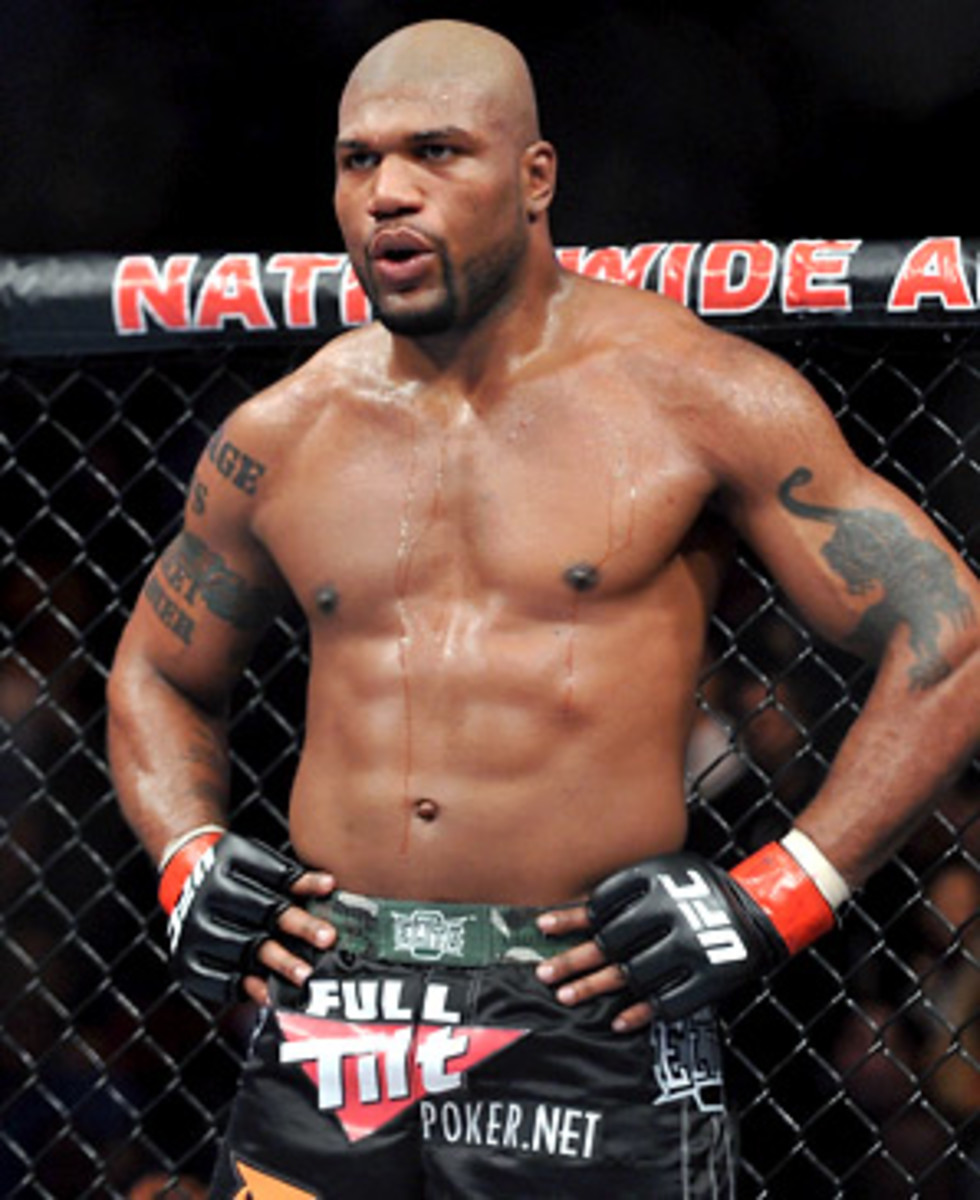

If you feel at all uneasy about the racially-tinged exchanges between Quinton "Rampage" Jackson and Rashad Evans, you're not UFC president Dana White.

There isn't a topic that engenders more passion than race, and like anyone else the man is entitled to his opinion. Yet I can't help wonder if White, the figurehead of a company and sport garnering more attention than ever before, missed the mark by piggybacking Jackson's misguided words to the selling of a pay-per-view.

As a nation we're decades removed from skin color dictating where people can eat lunch. Decades removed from Tommie Smith and John Carlos saluting in Mexico City. Decades removed from Muhammad Ali, Jim Brown, Texas Western. Decades removed from sports helping bridge the racial divide. The country, thankfully, finds itself in a different place.

But does it mean the issue is anywhere near settled?

Mixed martial arts has rarely, if ever, been in the position to address social issues. It's a young sport. An outlaw sport. By its very nature, those who know little about MMA presume thuggery and worse. The opportunity to enter such a discussion on the eve the first UFC main event to feature African-American fighters would have wrought an added importance. Instead, the UFC co-opted Jackson's "black-on-black crime" line to market Saturday's fight, cheapening rather than elevating the moment.

White, obviously, is not accountable for words he didn't say. But he is responsible for the use of those words in pay-per-view advertisements that seem to run every 10 minutes on television, none of which seems necessary. Imagine the NFL hyping a Sunday night matchup between Donovan McNabb and Terrell Owens by pushing the "black-on-black crime" line McNabb said about his former teammate in 2005. It would never happen, and you know why. It's inappropriate and out of place.

Jackson, 31, comes off as incredibly ignorant -- which is a shame because I know him to be insightful when he wants to be. He's not oblivious to race issues. Jackson liked to kid, no matter the promotion he fought for at the time, he was the "token black guy." But now Jackson says he doesn't care about race. He never thinks about race. Even if that were true, that does not give him license to ignore the power of words.

"My main objective is to entertain people," he said.

When he speaks the way he does, how entertaining is he really? And to whom?

Jackson should take the time to consider his growing influence, which will be heightened by a feature role in the big-budget film The A-Team. Are there any lasting consequences in speaking the way he does while millions of young people watch, giggling?

Here, Evans offers his indictment of Jackson, deriding "Rampage" for what he calls "Uncle Tom [expletive]." Evans' believes Jackson puts on a play built upon racial stereotypes because it's an easy sell to MMA's predominately white audience.

"He does his little Sambo thing, man," accused Evans, 30. "He does his little Sambo thing like oh 'black-on-black crime,' oh 'I'm stupid you can't use big words like that.' Like he don't know what the [expletive] is going on. Man, come on."

The more I've kicked this thing around in my head after first seeing the pay-per-view advertisement for UFC 114 a couple weeks ago -- culminated by Jackson forewarning some "black on black crime" on May 29 -- the more it's bothered me. I'm aware Jackson is a jester and I don't mean to come off as preachy. Actually, that's the last thing I want. But it rings unfortunate that MMA had a moment where it ran up against issues bigger than the sport, and not only did it ignore the impact of those statements, it twisted and turned them to an untenable place.

Feel free to disagree. I'd argue that by reducing Jackson's phrasing to a sellable sound-bite, UFC 114 sets a bad precedent for MMA. UFC officials are somehow suggesting this type of language is fine because it doesn't really mean anything, and White doesn't see a racial component because two black men are yelling at one another.

He's wrong.

In fact, it means a lot. Which is Evans' point.