Brazil now has flair for the effective

After England's 1-0 loss to Brazil in a friendly in Qatar last November, John Terry commented that he couldn't see anything to be fearful of. The injured Terry hadn't played in the game but had watched from the stands. His was a commonly held view. England had been outplayed, for sure, but there seemed nothing out of the ordinary about Brazil. It didn't shimmer with the sort of individual quality the stereotype demands it should. Even Kaka, the most celebrated of Brazil's lineup, is a muscular sort of playmaker.

Then Wayne Rooney emerged to give his view. Red-faced and sweating, he spoke in awe of the quality of Brazil, how well it had retained possession and how quickly and effectively it had closed down England. The mystery of this Brazil team was exposed in that juxtaposition between the experiences of watcher and player.

Since Dunga took charge in 2006, Brazil has won the Copa America and the Confederations Cup and led South American World Cup qualifying. In other words, the full side has won every tournament it has entered under Dunga's leadership. Yet this has been very much a stealth success. Dunga's Brazil is not garlanded at home, where its lack of flair provokes grumbling about not doing things the Brazilian way, while abroad it attracts only grudging respect.

Part of Brazil's strength is its reputation. As Rob Smyth put it in the Guardian, "The greatest trick Brazil ever pulled was convincing the world that joga bonito exists." The yellow shirts simultaneously intimidate opponents and bring the expectation of the flair that characterized Brazil's performances in the World Cups of 1970 and 1982. When Brazil doesn't play like that, it not only disappoints but also disconcerts. As its results suggest, this is an excellent Brazil side, but it is easy to underestimate. Its strength is the discipline of its pressing, which grinds away at its opponents, not giving them a second to breathe. It is not spectacular, but it is effective.

In Brazil, there are constant calls for Dunga to pick players with more flair. Last month, a Brazilian television channel ran a program arguing that the young Santos forwards, Neymar and Ganso, should be included in Dunga's squad. Nothing particularly unusual in that, you may think, except that they filmed the whole show outside of Dunga's house. Not surprisingly, he lost patience and called the police.

Then there is the issue of Ronaldinho. "If Ronaldinho continues to play like he has been at Milan, then it's right for him to go to the World Cup," Romario, the top scorer on Brazil's 1994 World Cup-winning side, told O Globo. "He knows what it means to lose a World Cup, and he also knows how to win one, like in 2002. He has done everything, and if I was Dunga I would call him."

Romario is just one of a host of pundits who want to see the AC Milan forward included. Dunga, though, considers him unreliable, and in a squad in which diligence is taken for granted, his relaxed attitude to training could prove disruptive.

Besides, Ronaldinho doesn't track back, something that was embarrassingly obvious in Manchester United's Champions League victory over Milan this season, when United right back Gary Neville repeatedly surged past him to join the attack. Dunga the manager, like Dunga the player, demands work rate. His misfortune is that that doesn't fit either the world's image of the Brazilian game or Brazil's self-image.

Brazil, though, cannot go back to 1970. That was the last hurrah of pre-systemic football, the last tournament of individualism, and even that was successful largely because the heat and altitude of Mexico made a hard-pressing game impossible (and Brazil was more tactically meticulous than many gave it credit for). By 1974, football was all about high offside lines, closing down the man in possession and manipulating space. The 1982 side of Zico, Socrates and Falcao was a throwback, but in the end it was found out by Italy. That Brazil team kept just one clean sheet in the tournament, and that against New Zealand. Zico spoke of Brazil's defeat to Italy as "the day that football died." More accurately, it was the day a certain ideal of football died.

Every Brazil side since has had a streak of pragmatism, concerning itself with what might be termed European virtues. Dunga even has his side playing that most European of formations, 4-2-3-1, albeit with a Brazilian slant. The European 4-2-3-1 developed from 4-4-2, with one of the center forwards moving back to play as an attacking midfielder while the two central midfielders take up a more overtly defensive role.

In Brazil, though, the default for years has been 4-2-2-2 (in 1982, the two holders were Falcao and Cerezo, essentially deep-lying playmakers; by 1994 those two holders had become the far more defensive figures of Dunga and Mauro Silva). The evolution of that system to 4-2-3-1 has come about by pulling one of the center forwards back and wider, while one of the trequartistas (literally a "three-quarter," a player who operates between the midfield and attack) shuffles a little wider -- and in the case of Ramires deeper -- on the other side to accommodate him. Robinho is thus a forward playing to the left, whereas a European version of the system would have a winger or a midfielder (or a defensive forward) there.

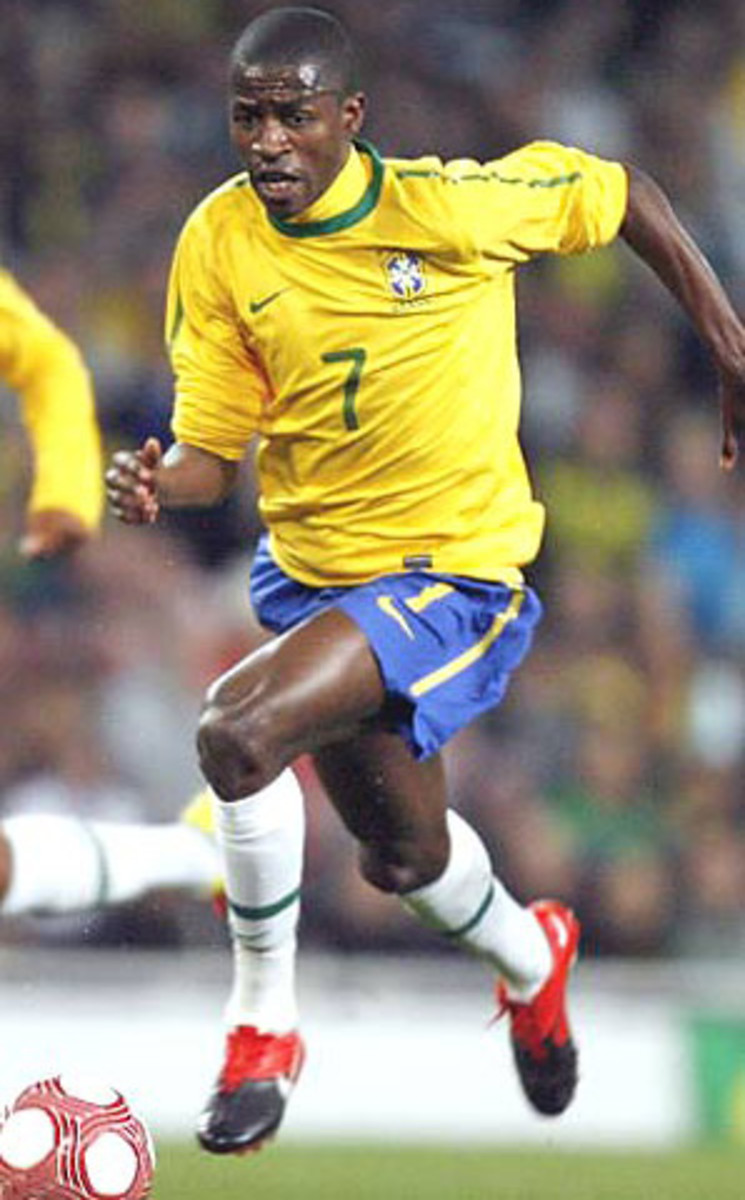

Ramires has become almost the archetypal Dunga player. BBC pundit Mark Bright branded him "un-Brazilian" after that friendly in Qatar, but the Benfica midfielder performs a vital role, chugging up and down on the right of midfield, allowing Felipe Melo, one of the two holders, to drift left to cover Robinho. Attacking thrust on the right tends to be provided from the fullback overlapping, whether that be Maicon or Dani Alves.

There is thus balance and solidity and, as the evidence of the last four years suggests, those attributes are rather more useful to winning trophies than trying to live up to some outdated ideal.