Saban and Slive are powerful men, but are powerless against agents

Three powerful men, essentially powerless to fight a group that works in the shadows and passes cash to players more seamlessly than the greasiest booster ever dreamed. In almost any other facet of college football, the coaches of the past two BCS champions and the commissioner of one of the nation's most powerful and lucrative conferences could effect change with a wave of the hand or with a nod of the head. But against the agents, the financial advisors and the runners, they can do nothing.

Pete Carroll couldn't stop it at USC. The NCAA blasted the Trojans' football program more for its tepid response to the Reggie Bush allegations than for the fact that Bush profited from his relationship with two wannabe sports marketers. Steve Spurrier couldn't stop it at Florida, where soon-to-be-imprisoned agent Tank Black funneled cash to the Gators' best defenders in the late '90s. Now at South Carolina, one of Spurrier's tight ends, Weslye Saunders, was interviewed last week by NCAA enforcement staff regarding improper benefits. John Cooper couldn't stop it at Ohio State, where agent Dunyasha Yetts passed cash to cornerback Antoine Winfield by intentionally losing at cards. Joe Paterno couldn't stop it at Penn State, where agent Jeff Nalley gave gifts to running back Curtis Enis.

The coaches can't stop it. The conference commissioners can't stop it. Despite the high-profile blitzkrieg it launched this month, the NCAA can't stop it, either.

Only two groups have the power to make a dent. The NFL Players Association decides who is allowed to represent NFL players and can yank the certification of an unscrupulous agent, but it has no dominion over financial advisors, marketers and the other remoras that circle potential NFL players hoping to siphon off scraps. (It should be noted that Lloyd Lake and Michael Michaels, the central figures in the Bush case, were not agents but marketers.) Truly, the only people who can police the larger group are the actual police.

In January, Illinois will become the 39th state to adopt the Uniform Athlete Agents Act, which calls for stiff penalties for anyone who passes himself off as a representative without a state license or for anyone who pays a college athlete with eligibility remaining. Since California, Michigan and Ohio already have their own non-UAAA laws, that leaves only eight states (Alaska, Maine, Massachusetts, Montana, New Jersey, New Mexico, Vermont and Virginia) that don't regulate agents.

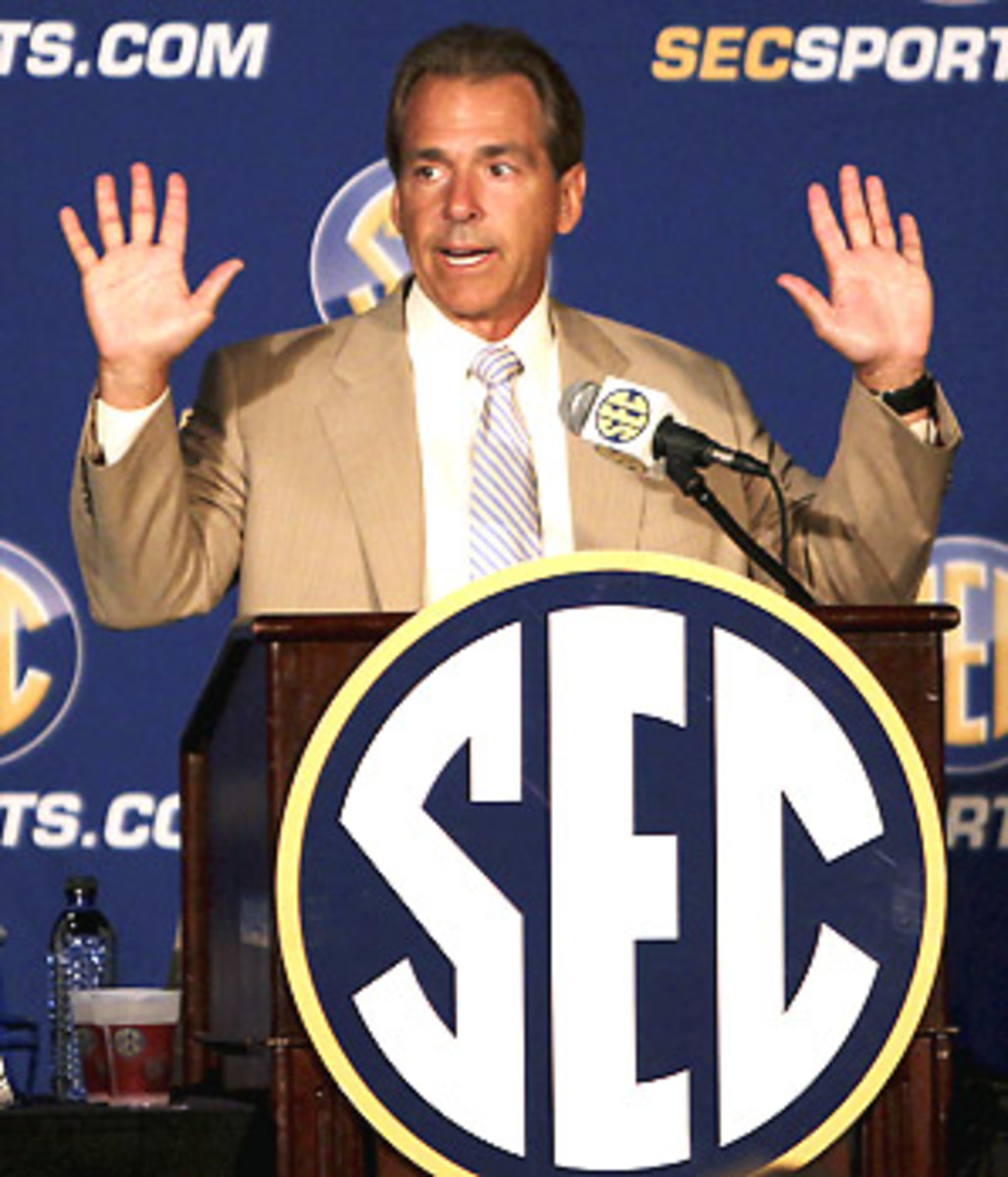

The coaches talked a big game Wednesday. Saban had the money quote. "I don't think it's anything but greed that is creating it right now on behalf of the agents," Saban said. "Agents that do this, I hate to say this, but how are they any better than a pimp? I have no respect for people who do that to young people, none."

Saban has suggested the possibility of banning NFL scouts from Alabama's campus as a way to pressure the league into taking action. That would only hurt the players he's trying to help, and it could harm the program. If NFL scouts were banned at Alabama, Auburn would mention prominently in its recruiting pitch that it welcomes NFL scouts. If the entire SEC banded together and banned scouts from campuses, ACC schools would use that to their advantage. Plus, such a move would drive the scouts to the agents and runners, some of whom are supremely gifted talent evaluators.

It's also a bit disingenuous that coaches are only now breathing fire about this issue. They've known about it for years, but it's bad for business if Saban, Meyer, Georgia's Mark Richt -- whose program also will get an NCAA visit -- or any other coach knows too much about the unsavory dealings of agents. The second a coach learns a player took something, he must suspend that player or risk having victories vacated. Since agents aren't bankrolling fourth-teamers, the coaches stand to lose a lot if they get too educated on the subject.

That brings us to the NFLPA, which does have a measure of power. Wednesday, NFLPA executive director DeMaurice Smith went on ESPN Radio's Mike and Mike in the Morning and said his organization wouldn't tolerate agents paying college players. "That's an insidious problem," Smith said. "Any agent or contract advisor who does that and preys upon kids like that in college is something we're going to deal with extremely aggressively. ... They'd get crushed on our side."

But they haven't been. Nalley received a two-year ban in 1998 for paying Enis, but most of the NFLPA's recent high-profile suspensions were for agent misconduct involving players already in the league. Even when the organization tried to help -- in 2006, it banned agent contact until after a player's junior season in college -- it backfired. The rule put the scrupulous agents at a disadvantage against the rule-breakers, and it had to be amended. Plus, the NFLPA only regulates contract advisors, and most of the dirty ones are smart enough to use intermediaries to avoid a direct connection between agent and player.

The only people who can stop those intermediaries work in law enforcement. Most states can charge runners or marketers with a felony for acting as an agent without a state license. It would behoove the NCAA to call in law enforcement in every agent case, because prosecutors have the subpoena power the NCAA doesn't.

In at least two of the cases currently under review by the NCAA, law enforcement has gotten involved. The University of Florida police department is investigating an accusation that former Gators center Maurkice Pouncey took money in December. (Pouncey has denied the claim.) Also, North Carolina secretary of state Elaine Marshall on Wednesday announced she would launch an investigation into agents at the University of North Carolina, where NCAA enforcement staffers interviewed several players last week about possible impermissible benefits. Marshall will leave the eligibility issues to the NCAA; she only wants to know what the agents did.

"We'll be investigating the agents," Marshall told WTVD-TV. "We will not be investigating the school."

If someone goes to jail in Florida or North Carolina for this, it might slow the flow of money from agents to players. The loss of freedom is a far worse punishment than the loss of a license.

The coaches and commissioners can talk all they want about pimps, but they're powerless here. Until law enforcement agencies begin treating unscrupulous agents and runners the way they treat actual pimps, nothing is going to change.