Struggle to milestone homer is same, but A-Rod is very different

Then? He couldn't do it. In fact, for a while, he couldn't muster a hit of any type. Over the next 10 days, he was all but shut down by a veritable No-Star team of Royals and Orioles and White Sox, many of them pitchers who are just three years later no longer in the big leagues -- pitchers like Brian Burres and Daniel Cabrera and Ryan Bukvich and Ryan Braun (not that one) and John Parrish and Odalis Perez and Jamie Walker. After that shot off Meche, Rodriguez went hitless in his next 21 at-bats, and homerless in 28, over 37 plate appearance. He just couldn't do what he had always done. This was like seeing Lady Gaga dressed in sweatpants, or that guy from Twilight unable to pop out an abdominal muscle. You almost felt sorry for him.

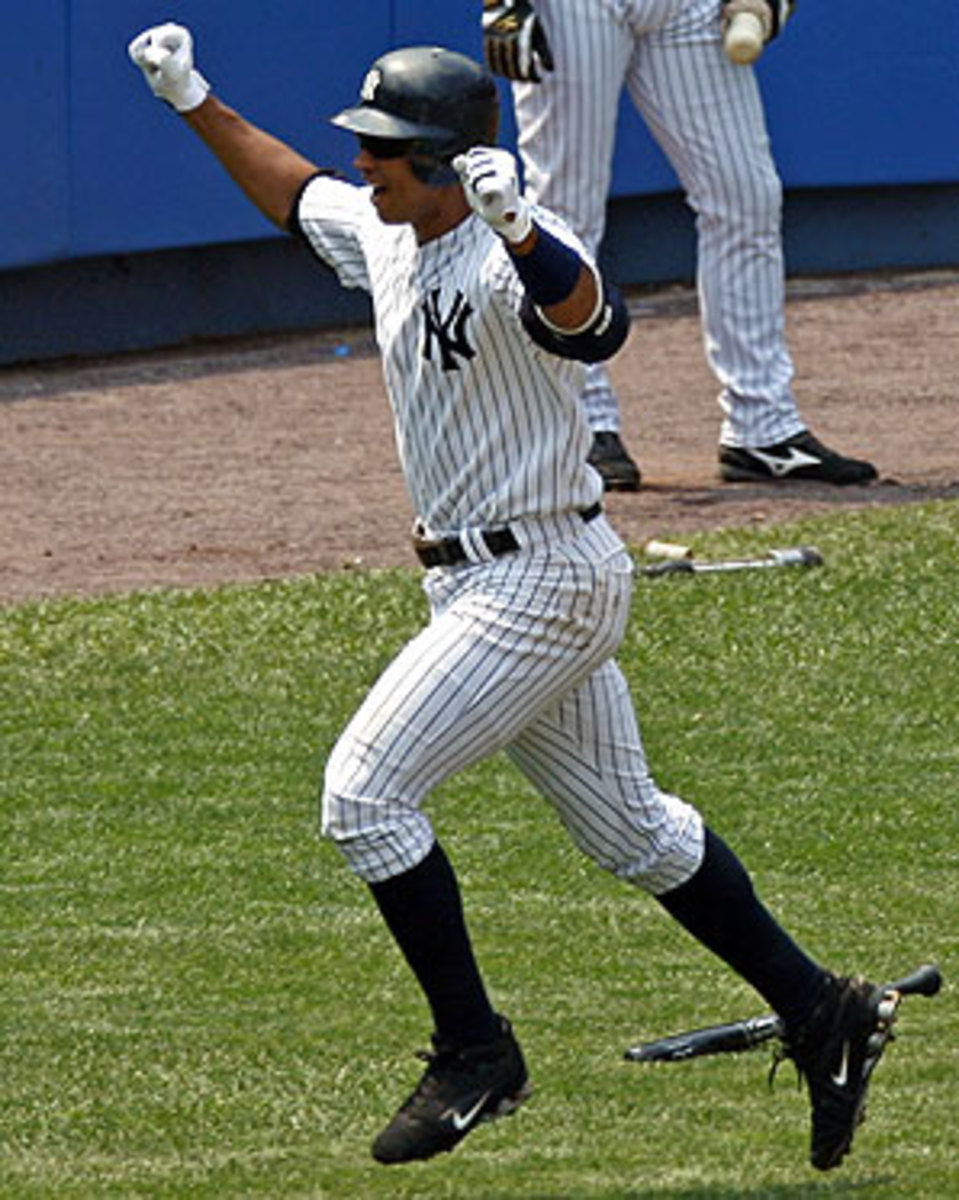

When he finally got there, with a first inning, three-run bomb off Kansas City's Kyle Davies in Yankee Stadium on August 4, it seemed more a relief than an achievement. After that, he was A-Rod again, and sailed along to what was by most measures the greatest offensive season of his great career, and one of the greatest anyone has ever produced: a .314 average, 54 homers, 156 RBIs, 24 stolen bases, his third MVP award. But the memory of his mid-summer struggle to reach 500 stayed with us -- especially given what happened in the years to follow. Now, as he again chases a historic home run -- his next will be No. 600 -- it is clear that memory stayed with him.

"For me, the whole thing as I approach 600, the whole thing that I think about is the perspective of where I was when I hit 500 and how things are different now," Rodriguez said last week during what has become a rarity for him over the past two seasons: a question and answer session with the assembled media in which he expressed slightly more than quotidian platitudes. "For me, early on, all I thought it was about was accumulating numbers. Try to hit 40 or 50 and drive in 140 or 130 and hopefully make the playoffs and maybe advance, but after winning a world championship and attaining that goal you realize that it is not about [numbers]. It is about obviously winning the world championship."

Rodriguez has never been adept at expressing himself in public, even when he genuinely tries. He has often seemed overwhelmed by the idea that people are watching everything that he does and that he is performing for them. The result is that most of what he does seems somehow robotic and artificial, as if he's overly conscious of what he is doing at that moment, or supposed to be doing, instead of simply being in the moment and doing it. When he makes an out, and jogs off the field, you can almost see him thinking, "Now I am supposed to casually trot off the field, slowly but not too slowly, perhaps shaking my head a bit." After he hits an important home run: "Now I am supposed to clap my hands and raise my arms in the air, and maybe high-five the third base-coach as I pass by him." When he gives a press conference: "Be humble but confident, credit your teammates, smile a lot and talk about how you want the team to win."

The situations in which Rodriguez appears to be completely natural, completely of and in the moment, are generally when he is in action on the field -- when he torques his body to produce that beautiful swing of his, when he makes a dazzlingly athletic defensive play. There is no time for forethought or artificiality then; nature takes over, and he looks, for once, comfortable. When he was chasing 500, however, during those frustrating 10 days, the other part of his personality seemed to bleed into that which had previously been inviolable. Instead of just hitting, as only he can, it was as if he were saying to himself, even as the pitch came in, "It is time for me, Alex Rodriguez, to join the 500 home-run club ... now." Of course, it wouldn't work. Baseball -- and, for most people, life -- doesn't work like that, even when you're Alex Rodriguez and they're Ryan Braun, not that one.

Why did Rodriguez develop as such? Part of it, we can imagine, is that since he was a teenager he had been A-Rod, among the most talented baseball players in the world. So talented that he was rarely questioned or criticized about anything by anyone who mattered to him. So talented that everything came so easy to him that he never had to think about changing. Angels center fielder Torii Hunter was born nine days before Rodriguez in 1975, was selected by the Twins 20th overall in the 1993 draft in which the Mariners picked Rodriguez first and has battled him in the American League for parts of 14 seasons now. He remembered the other day his first ever encounter with Rodriguez.

"It was 1992, and we were in Boise, Idaho, playing together on the Junior Olympic team, the South team," Hunter recalled. "This tall kid, a quarterback from Westminster High School in Miami walked in, 6'3", hands big as hell, a shortstop. Someone hit a groundball up the middle, he fielded the ball between his legs, turned around and threw the guy out at first. I'm like, damn, this guy is a straight athlete! Then he comes up to the plated with a wooden bat -- he was the only one using a wooden bat -- this taped up wooden bat, and boom, hits one 430 feet. We were both 16 years old, among the youngest there.

"I hadn't seen many baseball players," Hunter continued, "but these were like the top 100 baseball players in the country, and nobody stood out more than this guy. I go back home, and I tell everybody in my hometown in Arkansas. I said, dude, there's this guy named Alex Rodriguez. He's going to be the best player ever. They're like, better than Shawon Dunston? Because everybody believed in Shawon Dunston in my 'hood in Arkansas -- I don't know why, because he was playing in San Francisco, but they loved Shawon Dunston. I'm like, yes, better than Shawon Dunston. Ten times better than Shawon Dunston."

For the next decade or so, Rodriguez continued being 10 times better than Shawon Dunston. That he was 10 times better than Shawon Dunston may have led him to believe that anything he said or did (including, it turned out, taking PEDs) was the right thing and that those who criticized him were simply wrong, or jealous, because he was 10 times better than Shawon Dunston.

Then came his agonizing quest for his 500th home run, a crack in the façade. Then, in early 2009, the façade crumbled altogether. It was a perfect, image-shattering storm, beginning with the February revelation by SI's Selena Roberts and David Epstein that Rodriguez had used PEDs, and a month later the release of an embarrassing Details magazine photo shoot in which Rodriguez kissed himself in a mirror, wearing a muscles-revealing sleeveless shirt. Rodriguez at first tried to deal with the situation the only way he knew how, by putting on another show of artificiality at the press conference in the tent behind the third base stands at the Yankees' spring training home in Tampa. This time, however, no one was buying it just because he was so much better than Shawon Dunston. No one believed that he might actually cry during the 32-second silence in which he tried to squeeze out a tear. The emperor had no clothes; everybody knew it, and, crucially, he finally knew it. "I miss simply being a baseball player," he said plaintively that day, and after that day's disaster, he seemed committed to becoming that, and pretty much only that.

Later that spring, Rodriguez had surgery to repair a torn labrum in his hip and went away to Colorado to rehab. When he came back, returning for an early May road series against the Orioles, he was different, and still is different. "I think after coming back from Colorado and talking to most of the guys in Baltimore last year it's a lot easier, it's a lot more enjoyable when you think about doing the little things to help the team win," he said last week. That Rodriguez is still not a fluid communicator is underscored by tortured quotes such as that one, but these days he seems to finally understand this about himself: that people will no longer agree with or believe or validate whatever he says simply because he is so very good at baseball, and that it's not worth trying anymore. So he doesn't, not often.

A-Rod at 600 is a different person than was A-Rod at 500 because he now understands that the only thing that is fully under his control is what he does on the field. He understands that no one will buy the rest of his act anymore, so he is careful to keep it out of the public's view. That development seems to have unburdened him, suggest opponents and teammates. "For me, it seems like he's having a lot more fun -- a lot more fun," says Hunter. "He was always preparing himself early on in his career, he was always focused. He didn't say much at all on the field or anything like that. Now, he's cracking jokes, he's laughing more. Don't get me wrong -- he still prepares himself. We're in batting practice, and we see A-Rod in the outfield running, doing different drills, and I'm pretty sure he's watching film inside the clubhouse. But he's having more fun too."

His unburdening has also helped him to help his team win in ways other than his offensive production. "I can only speak for the last two years, but he's been a great teammate," says CC Sabathia, who spent one of his first days as a Yankee two years ago standing off to the side in one of his trademark many-XL t-shirts, watching his new teammate conduct his PED-use-admitting press conference, and probably wondering what he'd gotten himself into. "I know he cares a lot about the younger guys, teaching them and talking to them. Him and [Robinson] Cano are really close -- he's always talking to him. He tells guys what they need to be told, but he doesn't put himself out there and draw attention to it."

Last October, when I asked catcher Francisco Cervelli which of his teammates had most helped him transition from a .233-hitting minor leaguer to a rookie big leaguer who batted .298 and seamlessly filled in for an injured Jorge Posada, his answer was as quick as it was surprising. "A-Rod," he said. "He helps me with everything -- everything. I learn so many things from him, calling the game, offensively, defensively, game situations, everything. He's the man. Maybe he saw at the beginning that I want to work, I want to play, and he wanted to help me. I feel lucky to have him."

There is no doubt, however, about the identity of the person whom the new A-Rod has helped most of all: Rodriguez himself. He is no longer far and away the game's greatest offensive player. He is nearly 35, he has undergone a major hip surgery, and, it must be said, he is no longer a user of PEDs -- at least, we must assume that he is not. He is now just a very dangerous hitter -- perhaps Top 20, no longer Top 1. But what he has gone through between home runs 500 and 600 -- what, more properly, he put himself through -- has left him accepting of that, comfortable being what he is, and no longer desperately trying to convince himself and others that he is something even more. It has quite obviously been freeing for him. "I'm a little more relaxed," he said the other day, simply. We saw that last October, when he all at once cast off his reputation as a postseason choker and slugged six homers and drove in 18 runs in leading the Yankees to a World Series title -- their 27th, his first.

In between home runs 500 and 600, A-Rod the legend has died -- for us and for him -- and Alex Rodriguez the man was revealed. And it's Alex Rodriguez the man who will chase 700 home runs, and 763, and on from there.