Time for pass-happy offenses to return to basics of ground game?

Another high-flying NFL season is about to start, and that's great news for quarterbacks and for fans of the high-tech air assault that defines modern pro football.

After all, it's never been easier to pass the ball in the NFL. Just look at the long list of passing records that have fallen in recent years:

• Peyton Manning set the record for passer rating in 2004 (121.1).

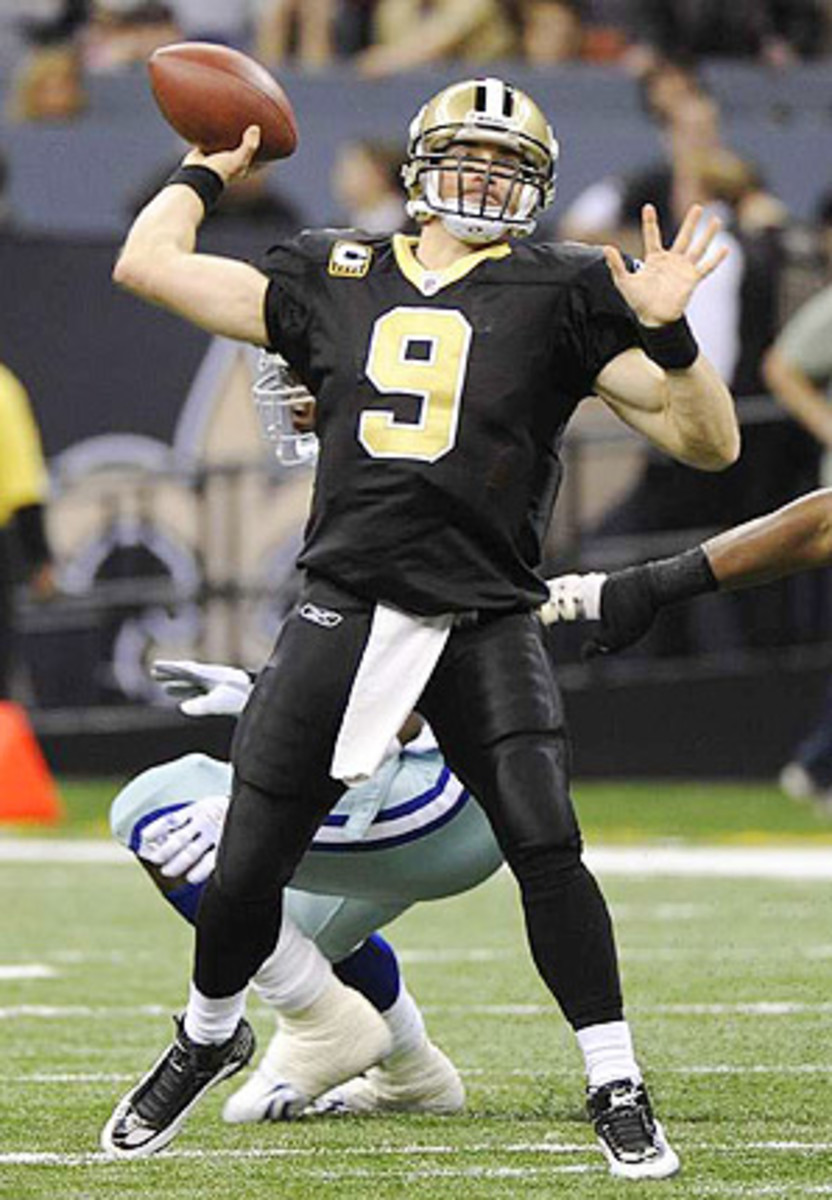

• Drew Brees set the record for completions in 2007 (440).

• Tom Brady set a new standard for touchdown passes in 2007 (50).

• Brees rewrote the record for completion percentage in 2009 (70.62).

• Brett Favre set virtually every career passing mark in recent years, including new standards for completions, attempts, yards and touchdowns that he'll pad here in 2010.

• And perhaps most importantly, the 2008 and 2009 seasons were the best passing years in NFL history, with record leaguewide passer ratings of 81.5 and 81.2, respectively.

With all the gaudy passing stats of the past decade, you'd think that scoring is at an alltime high, too.

But you'd be wrong. Way wrong.

The truth is the revolution in the modern passing game has not produced a revolution on the scoreboard. The truth is offenses scored at a greater clip back when the helmets were leather and the handoff was the preferred offensive weapon.

The Cold, Hard Football Facts recently conducted a study of annual scoring rates throughout the entire history of pro football and the results were shocking. In fact, the findings cause us to call into question the obsession that contemporary coaches, coordinators, quarterbacks (and even fans) have with the passing game.

The findings tell us that maybe it's time for a smart, cutting-edge offensive theorists to dial back the passing attack and show a little more love for the ground game.

After all, the single greatest season of offense in NFL history is not 1984, when Dan Marino thrilled the football world with his 48 TD passes and led the Dolphins to 513 points. It was not 2004, when Manning wowed us with his record 121.1 passer rating and 49 TD tosses while leading the Colts to 522 points. And it was not 2007, when Brees completed more passes than any other player in history while Brady connected on 50 TD tosses and led the 16-0 Patriots to 589 points.

Nope, the most explosive offensive season in NFL history was way back in 1948, when Philadelphia's Tommy Thompson led the NFL with 25 touchdown tosses and NFL teams averaged a record 23.2 points per game. Three of the league's 10 clubs averaged more than 30 PPG in 1948. To put that scoring clip into perspective, consider that just one of 32 teams, the Super Bowl champion Saints, topped 30 PPG in 2009.

Here's a look at the 15 highest-scoring seasons in NFL history. The explosive 1948 campaign is followed closely by a smattering of seasons from the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s. Modern seasons are few and far between:

We were stunned to find that 1948 was the high-water mark of offense in NFL history. We assumed teams struggled to put points on the board back in the leather-helmet days.

Certainly, most of us would assume that teams in 1948 ran far too often and passed far too little to score at any kind of great clip. At least that's the assumption, and it's partly true: NFL teams did run the ball far more often than they passed it in 1948, averaging 38 rush attempts and just 26 pass attempts per game. Compare those numbers with the 28 rush attempts and 33 pass attempts per game we witnessed in 2009.

But in the run-first season of 1948, teams scored at a clip never seen before or since, and the Cardinals, Eagles and Bears all topped 30.0 PPG.

Jimmy Conzelman's Chicago Cardinals were the best of the bunch. They led the NFL in scoring that year (32.9 PPG) and they produced what was probably the greatest four-week stretch of offense in pro football history.

From Oct. 17 to Nov. 7, the 1948 Cardinals beat the Giants 63-35; the Boston Yanks 49-27; the L.A. Rams 27-22; and the Lions 56-20. That's a four-week average of 48.8 PPG for those of you keeping score at home.

Yes, interceptions were far more common in 1948, so maybe that made life easier for offenses. The Cardinals, for example, picked off 23 passes in 12 games. But they scored just two defensive touchdowns all year, while adding four on special teams. Mostly, the Cardinals fielded an explosive offense that ripped off touchdowns at an incredible clip, nearly four per game and 47 total for the season. They kicked a mere eight field goals and, unlike offenses today, didn't (or couldn't) settle for the cheap, soccer-style field goals that pad scoring totals today.

The Eagles were No. 2 in scoring offense in that landmark 1948 campaign, with 31.3 PPG. Perhaps it's only fitting, in the greatest year of offense in pro football history, that the league's top two attacks met in the NFL title tilt.

But history has a way of messing with our minds, and the Eagles blanked the Cardinals 7-0 in a Philadelphia blizzard in that 1948 NFL championship battle, thanks to Hall of Famer's Steve Van Buren's five-yard TD plunge in the fourth quarter.

The 1948 championship game was remarkable for another reason: it was the first NFL title game shown on television (Red Grange was one of the announcers) and it represented a punchless end to the greatest offensive season in league history. Perhaps a cursory look back at the biggest game of the 1948 season might cloud our vision of what football was like back then. Fans might thumb quickly through the history books today, look at the 7-0 score, and conclude that the game was indicative of the low-scoring, leather-helmeted, war-of-attrition football of the era.

But the truth is that the 7-0 game was a great statistical outlier in the most explosive offensive season that the NFL has ever witnessed.

The 1948 season proved a pigskin portent of things to come in the 1950s and 1960s. Simply look at the greatest scoring decades in NFL history:

Once again, the list flouts conventional wisdom. Most modern football observers and analysts would assume that today's high-tech passing attacks have produced more points than ever. But it hasn't. Despite the rule changes of 1978 that spawned the Live Ball Era and the passing revolution, scoring has never reached the levels that fans witnessed in the offensive glory days of the 1950s and 1960s.

Many modern observers insist that the upstart AFL (1960-69) inspired an offensive revolution in the game of pro football. Indeed, AFL scores were often higher than they were in the NFL. The AFL's two most prolific seasons exceeded any the NFL has produced (24.5 PPG in 1961; 24.2 PPG in 1960).

But, as we noted last year when we refuted so many myths about the AFL, the scoring revolution in the NFL was already well under way by the time the new league came along in 1960. Sure, the AFL would produce prolific scoring -- but the 1960s remain the most prolific era of offense in NFL history, too, to this very day.

And, as we noted last year, the greatest individual offensive seasons of the decade all took place in the NFL, not the AFL. With or without the rise and impact of the AFL, the 1960s would go down as the Golden Age of Offense in the NFL.

We all marveled wide-eyed and gape-mouthed when Dan Marino passed for 48 touchdowns in 1984 and when Joe Montana produced what the Cold, Hard Football Facts consider the greatest passing season in history in 1989.

These performances were certainly a breath of fresh air in the wake of the defensive dominance of the Dead Ball Era of the 1970s, which reached its depths in 1977. NFL teams scored just 17.2 PPG in 1977, the lowest output since 1942. So the rule changes of 1978 that opened up the passing lanes were desperately needed. After all, the dramatic popular growth of the sport in the 1950s and 1960s seem to support the notion that football fans like points.

Those rule changes of 1978 succeeded in one very important respect: quarterbacks today pass more often and produce bigger, more spectacular numbers than ever before.

But maybe they've worked too well: modern offensive theorists are obsessed with the forward pass to the point that balanced offenses are few and far between these days.

And more importantly, as the Cold, Hard Football Facts prove, NFL teams do not score with more frequency than they did in the run-first 1950s or 1960s. (The disparity is even more shocking when you consider that field goal rates have skyrocketed since the 1950s and 1960s; teams should score more points today because of this fact alone.)

So maybe advocates of the ground game are right: maybe teams need to return to the fundamentals of football and "establish the run" to set up the pass. Maybe a little more dependence upon the ground game, and a little less dependence upon the pass, will produce the kind of explosive offensive production we witnessed in the 1950s and 1960s.

After all, the modern obsession with the passing game has delivered plenty of stats. But it has not delivered the pinball-type point totals we witnessed in the golden age of NFL offense, way back in 1948.