Reflections: 'Blood, Sweat & Chalk'

In the past three weeks, I have done dozens of interviews with radio stations, websites, blogs and print media as part of the publicity for my book, Blood, Sweat and Chalk. The Ultimate Football Playbook: How the Great Coaches Built Today's Game. It's a fascinating process and I'm thankful that almost every interviewer has been prepared and enthusiastic. I wish W.C. Heinz had been given a similar opportunity to talk about writing Run to Daylight with Vince Lombardi, because he would have killed, for sure and I'd pay to see the transcripts.

A book is a finished product; unlike a column on a website, there's no going back to add or subtract material. Yet in talking about BSC with peers, a number of questions have been repeated. Here they are, with some answers.

(Background: My intention with the book was to describe the evolution of various iconic offenses and defenses, by telling the story of the coaches who created -- or, more correctly, popularized -- them and in simple terms, the way in which these systems work. An excerpt was posted on si.com and you can read it here. If you want to buy the book, you can do it here. )

The questions, and the answers.

1) Who was the most influential coach in football history?

Almost every interviewer has asked this question, and, I'm not going to lie, it's impossible to answer with any authority. Football is a relatively complex activity and coaches are constantly tinkering with the deployment of the 22 bodies on the field. There have been countless evolutionary leaps in the past 110 years since governmental intervention helped outlaw the Flying Wedge and created the basics of the modern game of football.

That said: Pop Warner was some smart guy. He essentially created the single wing (maybe with some help from Amos Alonzo Stagg), and drew up principles that are very much in play in the modern game: Dominance at the point of attack, deception in the backfield, putting the ball quickly and efficiently in the hands of the best athlete on the team. You can see 50 teams do each of these every Friday, Saturday and Sunday and Pop had it figured out in 1906. Not bad.

Then there's Dave Nelson, who with Mike Lude transformed the single wing into Wing-T in the early 1950s and then took it to Delaware. It remains one of the most popular high school offenses in the country and remember, most of the country's football is played in high schools.

Bill Walsh truly invented the West Coast Offense. Buddy Ryan truly invented the '46.'

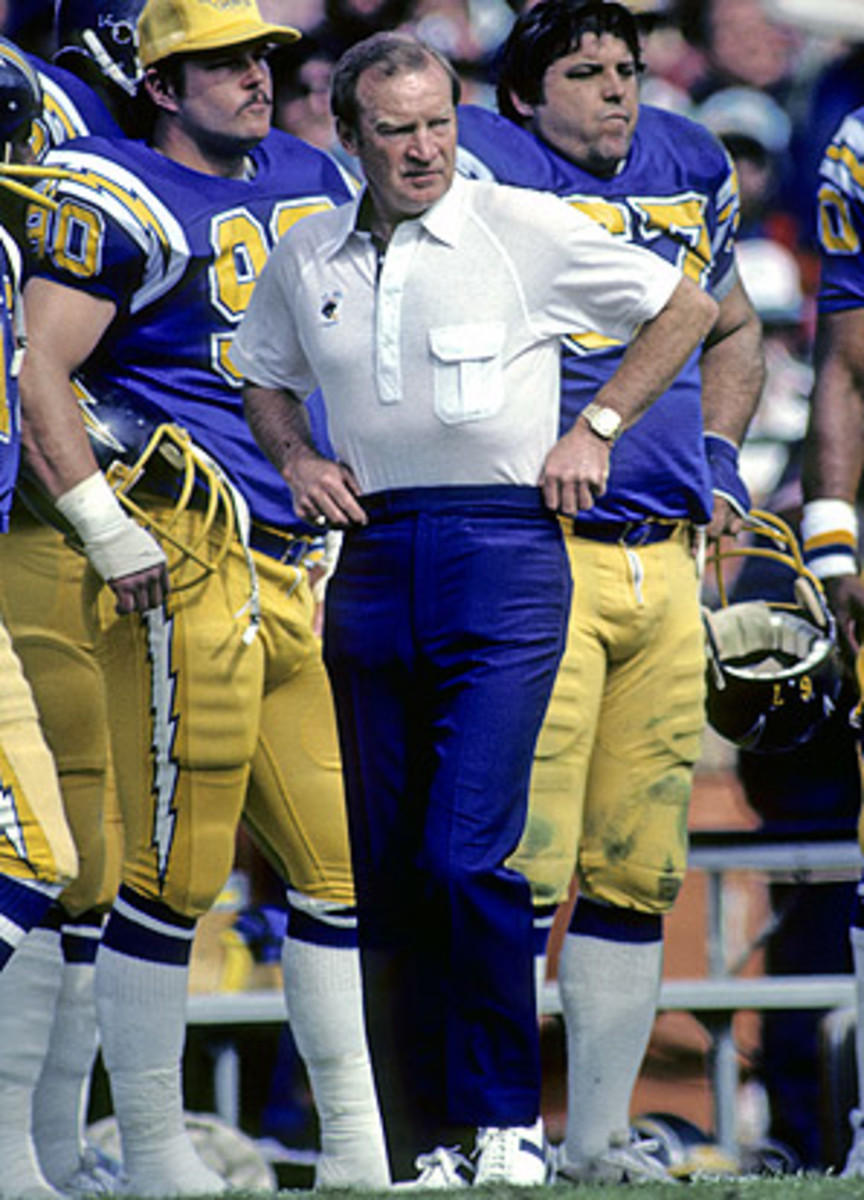

But I would go with Don Coryell. Sports Illustrated published an excerpt from the book on Coryell when he passed away in early July. All Coryell did was help -- maybe more than help -- John McKay install the Power-I at USC in the early 1960s, leading to the development of Student Body Right and Student Body Left and eventually, to the power running game that John Robinson took to the NFL. Then, a few years later, Coryell installed the downfield passing game (certainly with some influence by Sid Gillman) that's a staple in the NFL even today.

Which brings us to....

2) What's the biggest change in football from the "past,'' to "now?''

Yes, the question is usually that vague. And fair enough. There's no doubt where football has gone in the past, say, 40 years: From the run to the pass. As Kerry J. Byrne of Cold Hard Football Facts wrote on SI.com last week, this hasn't led to more points, but it has fundamentally changed the structure of the game. It's why Coryell, Walsh and even Mouse Davis (see below) are central to evolution of the sport.

3) Do you actually have a copy of Coryell's pass route "tree?''

I do. As I explain in BSC, I talked with Coryell in the winter of 2008 at his home in Friday Harbor, Washington. Coryell talked me through his offensive system by referring to the San Diego Chargers' 1979 playbook. Included in that playbook was a very basic and precise listing of the Air Coryell passing route system, in which outside receivers' routes were numbered from one to nine and inside receivers' routes were numbered from 10 to 90. The diagram of the route tree is accompanied by intricate descriptions of each route.

One of the best moments in reporting the book was going from Coryell's home to the public library in Friday Harbor, where I copied some 50 pages of the playbook. (Don didn't want to just give away the playbook's pages, so we stood next to the copier, dropping in quarters, old school). I volunteered to drive the SUV from Don's house back downtown to the library and ferry, because Don's knee was sore after recent replacement surgery. He was incredibly thankful that I volunteered to drive; I can't overstate how nice Don was to me, and how privileged I feel to have done the last significant interview of his life with him.

One of the interesting things is that almost every football program in America that throws a modicum of passes now has a pass route tree. Was Coryell's the first? As I say with everything in the book, there's no way to be sure. But I would argue that his is the most enduring.

4) Who was the most interesting person to interview?

Going back to question No. 2. Because of the proliferation of the passing game at all levels, I'm going with Darrell (Mouse) Davis on this one. Certainly Walsh and Coryell were more important figures at the highest levels of the game.

But at the time when I sat down with Mouse at a breakfast joint near Portland State in the fall of 2008, the spread offense had taken over just about every level of the game. There were many different spreads, but whether you were talking the four-wide Patriots with Tom Brady or a high school team in Kentucky, spreads were everywhere. "Grass basketball,'' said Renzie Lamb, one of my coaches at Williams College, when I saw him at homecoming that same fall. "That's all you see now.''

And as I sat down to poached eggs with Mouse, I still wasn't sure how we got here with the spread. Then Mouse took me first backward, and then forward. Backward to Ohio high school coach Glenn (Tiger) Ellison's groundbreaking textbook on the Run and Shoot offense, written in the late 1950s. Forward to Steve Spurrier and Josh McDaniels and every coach who spreads the field. Never was the connection of past and present more apparent. (As an aside, while hitting NFL training camps this summer, I talked with Ravens offensive coordinator Cam Cameron, a serious student of football history. He said, "Nobody runs the pure Run and Shoot anymore, because your quarterback gets killed. But everybody who spreads the field owes a debt of gratitude to Mouse Davis.'' And Tiger Ellison.

Afterthought: Mouse Davis, who will turn 78 on Sept. 6, is the offensive coordinator at the University of Hawaii.

5) Who is the unnamed player on the cover?

Ravens linebacker Ray Lewis.

6) What did you leave out of the book?

That's a dangerous question, but let's be honest: The book is 256 pages and 22 chapters. It could be triple that. Before the process even got rolling, I tried to make a list of offenses that should be in the book (West Coast, Zone Blitz, wishbone), and then started adding from there. But I figured out pretty early in the game that I wasn't going to get to all of them, at least not get to all of them in a way that allowed me to tell some stories, too. And that was the goal.

Enough whining. The next book will include the ''T'' formation, which was significant to the middle of the 20th century. When I was at Chiefs' training camp earlier this month, Scott Pioli reminded me of Bill Belichick's vital role in transforming the position of nickel back. That will be in the next book, too.

7) Why did coaches talk to you? After all, they're football coaches. They don't talk to anyone.

True, football coaches guard their secrets. But it turns out that's really only when you're asking them about this weekend, or this particular team. When you ask them about history, even recent history, they are actually a very forthcoming lot.

Example: In the fall of 2008, when the Wildcat was first hitting the NFL (it had been around in high schools for a decade, thanks to Hugh Wyatt, and in colleges for half that long, thanks to Gus Malzahn), I inquired of the Patriots if Belichick might like to talk to me about the single wing, which was the basis of the Wildcat. Belichick not only talked, he talked for 45 minutes, and gave me a great education.

There were numerous other examples. Coaches went out of their way to give credit to previous generations from whom they had learned or stolen. They were generous in explaining the intricacies of complex offenses and defenses so that I could further explain them to readers.

Even those that were gone -- Warner, Nelson, Lombardi, Walsh -- left behind road maps that were easily and fascinatingly followed.

8) What did you learn?

That coaches and athletes like talking about their jobs more than their lives, and we probably don't ask them enough about their jobs and too much about their lives.