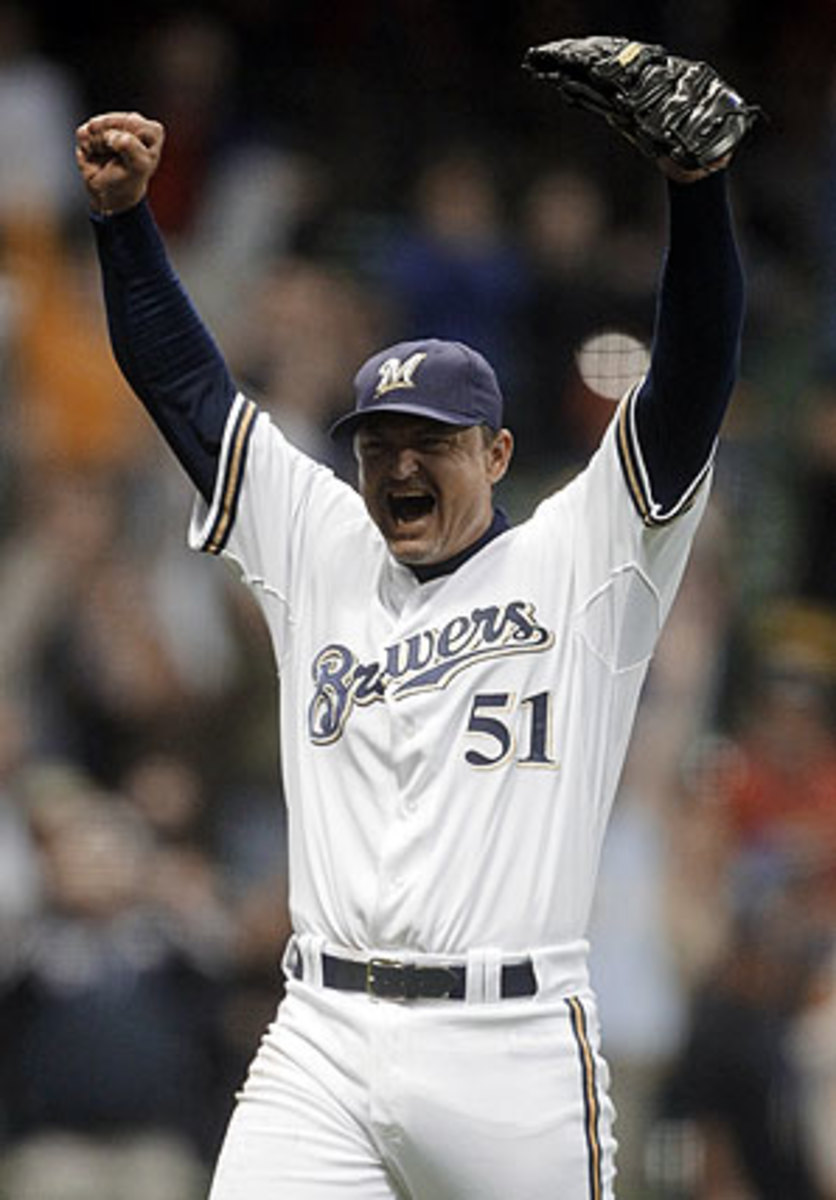

Hoffman's march to 600 wasn't pretty but it deserves praise

Before he became the first man to save 600 games, I had no idea Trevor Hoffman was pitching so poorly this year. I wish I had; the slow limp toward the end of a great career is always worth appreciating.

When you think of players holding on too long, you might think of Willie Mays falling down in the outfield in the 1973 World Series, or Pete Rose penciling himself into the second spot in the batting order in 1986, or Ken Griffey, Jr. napping in the clubhouse this year. I think of David Cone, not in his infamous 2000 season, when he managed a 4-14 record for the Yankees at the height of the Torre dynasty, but in 2003, when he tried to come back with the Mets while sporting a fastball that ticked 85 at good moments.

Cone died out there and retired after a few beatings, and while it lasted it was like watching an old sharpshooter try to pick Apache helicopters out of the sky with a rusty musket, but it was also unusually honest and creative pitching. He knew he had nothing, and so he was trying every trick he knew to make the hitters get themselves out.

It might even have worked if his arm had been just a bit less torn up. Usually pitchers who know so well what to do and are so unable to do it are coaching. Nothing will make you appreciate just how intensely physical baseball is more than watching someone as smart as David Cone fail as badly as he did as trying to think his way through a lineup.

There are, of course, arguments against allowing a burnt case like Cone or Hoffman to play, not all of which involve patronizing players by insisting that they help preserve our pure memories of their vibrant youths by just going away.

A team, goes one such line, should be merciless in pursuit of victory, and, at the exact moment when it's clear an old man is done, get rid of him even if he's chasing some round number like 200 wins or 600 saves or 3,000 hits. To do otherwise is to cheat the public.

Another is that allowing Methuselahs on the field cheats younger players. Allowing Hoffman the chances to pick up save 600, for example, took opportunities away from 27-year-old Brewers closer John Axford, to whom a few saves might matter when it comes time to negotiate a new contract.

Both arguments are obviously right, and yet it's hard for me to care. A game in which sloppy sentimentality played no part would hardly be a game worth watching. And the adulation Hoffman is receiving this week offers, just as Cone's final few starts did, a perfect example of why.

If we're honest, we'll admit that Hoffman has never, with the exception of his glorious 1998, really been a great pitcher. This has less to do with closers being inherently overrated than with how good he's been. The average, competent closer will have an ERA of somewhere between 2.50 and 3.00; Hoffman's career ERA is 2.87. He's had better years and a few lesser ones, but he's mainly spent two decades being pretty good.

Being pretty good for that long is difficult, maybe more to some ways than being great. A truly great player will adapt as he ages because he does several things well and can get better at some even as he gets worse at others. A player who does one thing well -- and that describes the vast majority of even good major leaguers, who can maybe field a bit or hit a home run now and then or throw a nice fastball -- has almost no margin for error.

Hoffman has always been such a player. He had some significant virtues such as composure and the ability to pitch an inning every third day without hurting himself, but basically he owed his success to one thing: a change-up. In his prime it was just hideous, and then as he lost a bit to age he figured out how to keep it working well enough to do his job, solidly and well, for long enough that he'll almost certainly make the Hall of Fame.

Cone's final weeks as a major leaguer taught me just how much heart and intelligence count for in the absence of other virtues. Hoffman's big day reminded me of this: There is a broad middle class of ballplayers who don't make the covers of national magazines or inspire long odes to their brilliance, but serve as the spine of every decent team. You take it for granted that such players are always going to be perfectly okay, until you look up one day and they aren't, and then they're gone. Good on the Brewers for giving one of them a chance to do something no one has ever done, and remind everyone who he was.