Platelet-rich plasma therapy: not new, no performance benefit

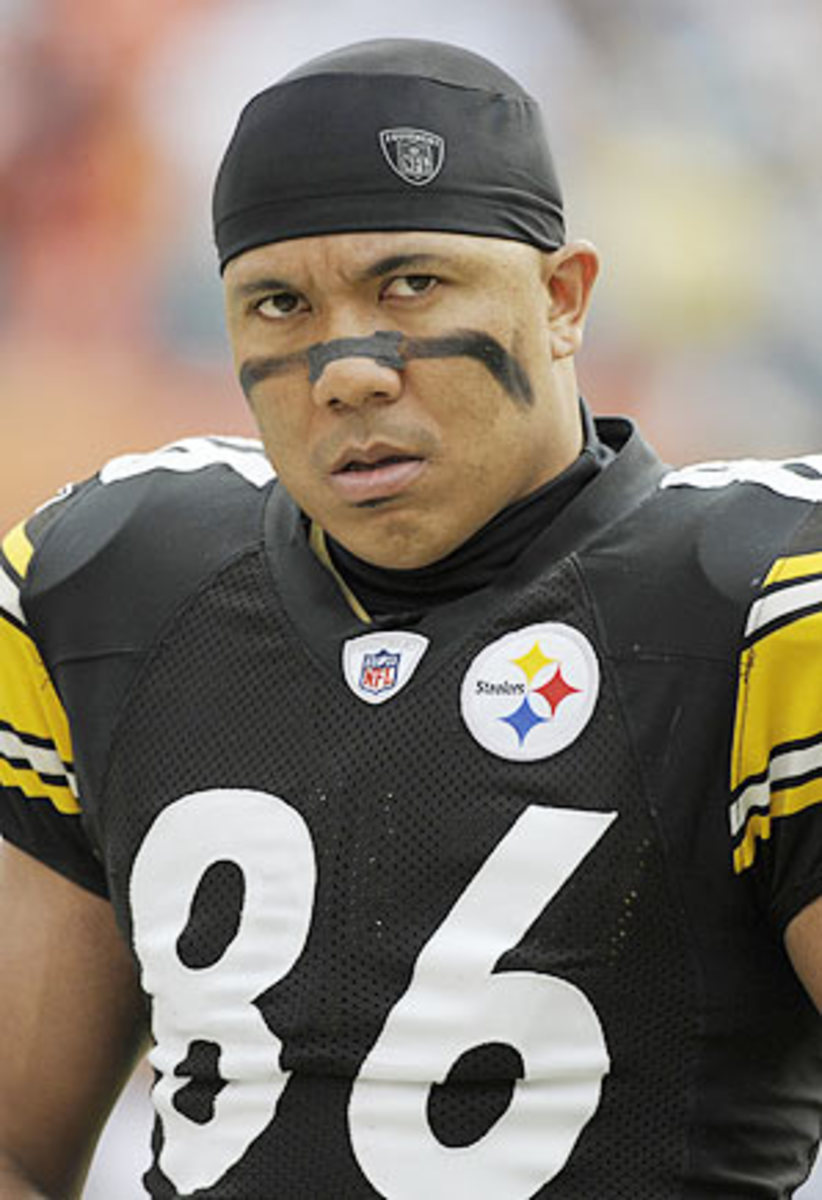

The public revelation of Ward's treatment prompted widespread Internet speculation that the procedure, which involves extracting a patient's blood and then re-injecting a portion of it, was tantamount to blood doping. It isn't. In the most typical form of blood doping, blood is extracted from an athlete and then re-injected after enough time has passed that the athlete's body has replaced the lost blood on its own. The result is an increased number of oxygen-carrying red blood cells in the athlete and a hearty endurance boost.

Platelet-rich plasma therapy provides no such advantage. In PRP, about two tablespoons of a patient's blood are extracted and spun in a centrifuge until the red cells are separated from a concentrated dose of platelets. Platelets, which are responsible for the clotting following a cut, contain substances called growth factors, proteins that promote the growth of soft tissue such as ligaments or tendons. In PRP, the platelets are injected immediately back into the body. No red blood cells are injected and no performance benefit is gained.

While Galea's use of PRP on Tiger Woods and other athletes has stirred debate, the technique is not particularly new. Allan Mishra, adjunct clinical assistant professor of orthopedic surgery at the Stanford University Medical Center and a pioneer of PRP therapy, has been using it for nearly a decade. In a breakthrough study last year based on work by Mishra, PRP therapy performed significantly better than cortisone -- and with fewer side effects since it makes use of the patient's own blood -- in the treatment of chronic lateral elbow tendinosis, aka tennis elbow. "I can say pretty definitively that PRP is a reasonable choice for tendon [injuries]," Mishra says. "Now it needs to be studied in other applications."

A study published in January by Dutch researchers, however, found that PRP therapy was essentially no better than a placebo in the treatment of chronic Achilles tendinopathy. At a sports medicine lecture in Vancouver in March, Galea recited to SI a number of what he considered flaws in that study, including the fact that participants were given only one PRP injection and with too low a concentration of platelets.

With the use of PRP therapy growing fast among athletes, the World Anti-Doping Agency -- which has no dominion over the major American pro sports -- decided for the first time to publish PRP rules, which took effect on Jan. 1 of this year. Under those rules, PRP injections into tendons and joints are allowed by WADA, but injection into muscles, like the treatment Canadian figure skater Patrick Chan received from Galea last year while preparing for the Vancouver Olympics, is banned without a special exemption, due to the possibility that it could stimulate not only muscle healing but also muscle growth.

PRP's banishment will be short-lived however: On Saturday WADA announced that intramuscular PRP will be removed from the 2011 prohibited list, citing the "lack of current evidence concerning the use of these methods for purposes of performance enhancement."

According to the announcement, "WADA will however, continue to closely monitor developments of these preparations."