Harvard looking to finally claim its spot atop a deep Ivy League

HARTFORD, Conn. -- The postgame press conference was brief, befitting a blowout loss. Harvard coach Tommy Amaker generously praised then-unbeaten Connecticut for its size and talent, noted that his Crimson players may have been a bit intimidated early, and then quickly headed back down the wide, echoing corridor of the antiquated XL Center after UConn's 81-52 victory last week. There really wasn't much more to say.

"I was cringing having to watch that [performance] and knowing that you'd walk away thinking that about our league," Amaker said by phone this week.

In the bigger Ivy League picture, though, there's plenty to talk about. This season is seeing new levels of competitive balance and depth, and after decades as the league's sleeping giant, Harvard is clearly on the rise.

Harvard has never won the Ivy League title in men's basketball, which makes it about the only thing the school hasn't been first in at some point. Frankly, up until the Crimson dismissed Frank Sullivan in 2007, after 16 seasons and a 178-245 overall record, Harvard hadn't really tried. The Crimson were the Ivy's most self-restrictive program, often watching nominal recruiting targets end up somewhere else in the league and suffering the consequences. Of course, they also were buried in a conference that, at the time, had been won 19 straight years by either Penn or Princeton.

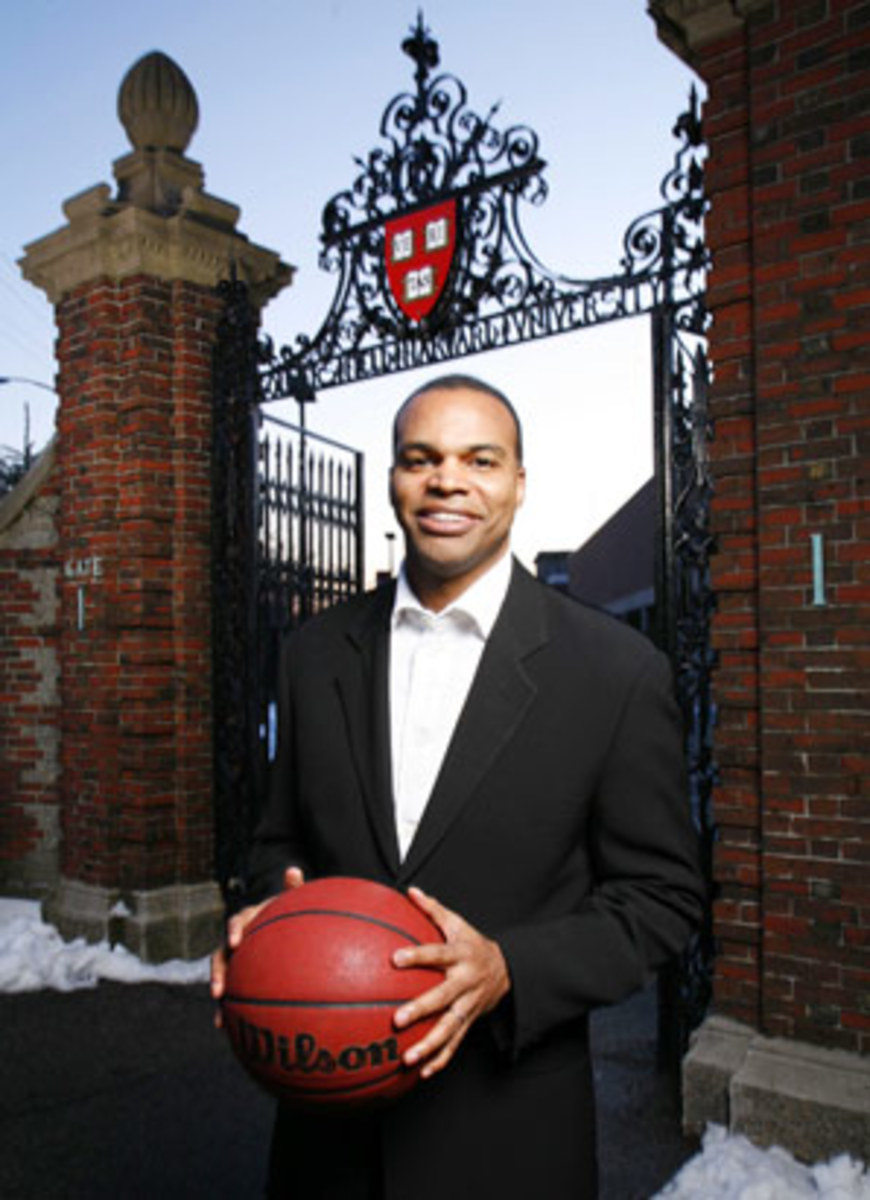

At Amaker's introductory press conference that spring, athletic director Bob Scalise said that Amaker was promised the "resources" to be able to compete for league championships. Asked to elaborate, Scalise said it was about money for staff and promotion of the program and also "moral support" and "commitment" to establish Harvard, which has the nation's largest athletic program, as a school with more than one or two primary sports.

The Crimson's surge from 8-22 in Amaker's first season to last year's 21-win campaign that yielded a spot in the postseason CollegeInsider.com tournament has been impressive. It also has carried a whiff of controversy, both overtly in the form of a secondary recruiting violation involving now-assistant coach Kenny Blakeney and more opaquely in comments from around the league concerning the Crimson's newfound emphasis.

In a 2008 New York Times story on the Crimson, Yale coach James Jones said there had been a drastic shift in Harvard's admissions philosophy and that Yale "could not get involved with many of the kids that they are bringing in." Two of Sullivan's former assistant coaches echoed that sentiment. Almost three years later, as Harvard continues to win recruiting battles, that perception still exists, despite denials from the school that it relaxed its standards for Amaker. Princeton coach Sydney Johnson said this week that he has noticed increased determination all around the league, leaving it somewhat unsaid that the signs coming from Cambridge were the boldest.

"I think it's very, very clear that Harvard's signaled to everybody that they want to be good in men's basketball, and you can either sit by and let it happen or react," Johnson said. "Whether it's recruiting, whether it's marketing of the program; I definitely think it's admissions, I definitely think it's financial aid."

The non-scholarship league has myriad financial aid rules that allow schools to attempt to match packages offered by a league rival, so Harvard's enormous endowment and liberal grant plans often aren't the key advantages they may seem. The real difference is in who the Crimson are going after, which are much better basketball players, some of whom may have lesser academic profiles than traditional Harvard recruits. That's not necessarily a bad thing.

In truth, almost any Ivy League recruit would be the academic envy of most other Division I programs, so the big picture is complicated and tinged with shades of gray. It's about reputation and institutional emphasis in a league that sometimes is embarrassed by sporting success. It's about double standards in what's OK for one program but not another. It's about jealousy and protecting the status quo.

Whatever Harvard is doing (or not doing), it's working, and the competitive landscape in the league has changed as a result. The Crimson's current roster contains a promising batch of 11 freshmen and sophomores and Harvard beat Penn for highly touted big man Kenyatta Smith, who will arrive next year. There are no seniors, which makes the Crimson one of the nation's youngest teams and one that is carrying Amaker's stamp.

"We think there are more kids out there [that fit the Ivy League] than some people initially think," Amaker said. "I've been around other schools, high-academic institutions, and I think there are a lot of kids who fit the profile if you can present who you are, your vision, and obviously your university."

As long as Amaker sticks around, Harvard's ascent seems inevitable, but a coronation may have to wait. Cornell, which became the league's first Sweet 16 team since 1979 last winter, graduated its core, but this season's Ivy is still the toughest in recent memory. According to CollegeRPI.com, the league is 12th in conference RPI, ahead of the Missouri Valley, Western Athletic and West Coast conferences. Six of the league's eight teams are in the RPI's top 175 and at least four have a shot to win the league title. That makes this easily the best Ivy season since 2002, when there was an unprecedented three-way tie at 11-3 between Penn, Princeton and Yale.

"I think this year is deeper [than 2002] because I don't think there's a bad team in the league," Yale's Jones said. "I look around the league right now and I don't know where the wins are going to come from. Anybody could beat anybody, or at least that's what it looks like on paper, anyway."

Can Harvard end its drought this year? While balanced and talented, the departure of star Jeremy Lin leaves the Crimson lacking a player who can consistently create his own offense. There's also an unwritten rule in the Ivy -- with its quirky Friday-Saturday league schedule and lengthy, late-night bus rides between road games -- that good, experienced teams beat good, young teams. That's why Princeton, which returns all five starters from last year's squad that pushed Cornell to the wire twice on its way to a second-place finish, is viewed as the favorite, as much for its ability to grind out the necessary wins in a very deep league as for its own talent. Of course, there's also the incentive of a long-standing legacy for the traditional powers to protect.

"As a Princeton guy, my love is for this program, so let's have a response," said Johnson, who was the league's Player of the Year in 1997. "Make sure we respond to somebody trying to take what we established. That's the fun part. The fun part is competing. You don't want to just walk your way to a championship. You want to compete."

There's little doubt that Harvard is ready to compete and that the rest of the league should get used to the change. And if the Crimson finally make the NCAA tournament for the first time since 1946, Amaker will have achieved his overarching goal for the Crimson's basketball brand to resonate with the same quality as everything else at the school.

"If we're going to have the name Harvard on it and be a part of Harvard and represent Harvard," he said," we want to see if we can position ourselves to be the very best in what we do."