Reds are well-acquainted with life after Tommy John surgery

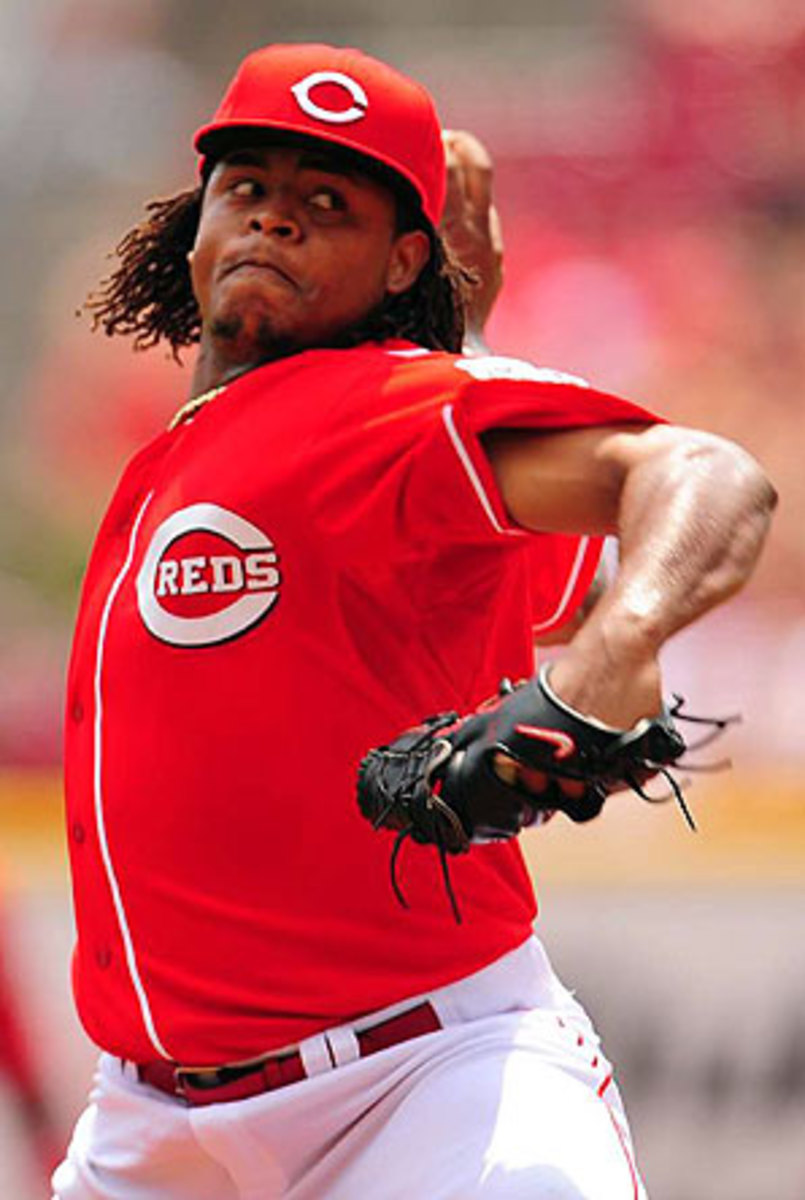

GOODYEAR, Ariz. -- Just 11 months removed from his August 2009 Tommy John surgery, Reds starter Edinson Volquez was back pitching in the majors. Two months after that, manager Dusty Baker named Volquez his Game 1 starter in last October's National League Division Series against the Phillies.

At the dawn of spring training, Baker announced that Volquez would be Cincinnati's Opening Day starter, a job that only stood to be threatened by lingering visa issues that now appear to be resolved after the pitcher returned to his native Dominican Republic.

And there's this statement, delivered by Reds pitching coach Bryan Price on Monday morning: "It's a given that [Volquez] has some of the best stuff in the league from what I saw before he got hurt and what I've seen since."

Talk about confidence in a 27-year-old who has made only 70 career starts over six seasons, exceeding 12 only once, even if it was a dazzling 2008 campaign in which Volquez went 17-6 with a 3.21 ERA. He has thrown just 113 1/3 innings since, including 62 2/3 innings with a 4.31 ERA in 2010.

But as an organization the Reds are one of baseball's best-equipped clubs in the treatment of pitchers with catastrophic elbow injuries. About a dozen pitchers in the Reds organization have had Tommy John surgery, including four in big-league camp: Volquez, Jose Arredondo, Bill Bray and Justin Lehr.

In fact, Reds chief medical director Dr. Tim Kremchek, who performs some 100 to 150 Tommy John procedures each year (20 to 25 on pro ballplayers), said that he recently reviewed data from his past 700 ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction surgeries -- the procedure's proper name -- and found that a staggeringly high 96 percent of them return to the same level of competition where they were before the operation. That figure, he said, may even be higher for major league pitchers.

That gives Baker, Price and the rest of the Reds staff the confidence to anoint Volquez their ace despite his relatively modest recent track record at the big league level. The team's medical staff has pronounced Volquez to be 100 percent healthy and restriction-free this season.

And though many critics have pointed fingers at Baker for the arm injuries to young phenoms Mark Prior and Kerry Wood under his watch when he was manager of the Cubs, Reds fans can rest easy knowing that the franchise employs a more collaborative effort in determining usage, meaning that the club's left-handed fireballer, Aroldis Chapman, is unlikely to be burned out by overuse.

Chapman will pitch out of the bullpen for a second straight year before likely being transitioned to the rotation next season. Price said that he has made only a minor tweak to Chapman's delivery, by getting the lefty to not crouch so much before delivering the ball. The forward-spring action from his legs can threaten to get too far ahead of his body and damage his arm if it's dragging behind.

It's a longstanding belief in baseball circles that pitchers return from Tommy John surgery better than before the operation. The predominant theory is that the work done on the UCL strengthens the elbow and allows a pitcher to throw harder than before the operation.

But that's not really the case. Sometimes a pitcher's apparent velocity gain can be explained by the idea that they are simply returning to the level they should have been at all along. Pitchers who need Tommy John suffer from a slow deterioration of the UCL, which weakens the elbow and reduces their velocity.

Kremchek also noted that many injured pitchers hadn't properly adhered to a strengthening program but that the aggressive, year-long rehab program after the operation can add velocity.

"Most guys who have been through this and missed a year of the game do it," he said, referring to the tough rehab. "They are so afraid to go through it again and what it would do to them, they live the program."

In having performed the operation as often as he has, Kremchek has made some discoveries that counsel the conditioning programs he prescribes. Namely, he says that training of the core muscles -- both the flexibility and strength of the abs and the lower back, which the club measures for each pitcher in spring training -- is of the utmost importance. Pitchers with a history of back problems are more likely to develop elbow problems.

Kremchek has also noticed another trend: Players who begin pitching early in their lives are actually less likely to later need surgical repair, which seems counterintuitive. One might assume that the extra years of wear and tear would take their toll, but, the doctor noted, if a pitcher starts early enough, his body adapts.

"We know that a young man who started pitching at a young age -- that's like seven, eight, nine years old -- has less tendency of injury in his shoulder and elbow than somebody who started pitching at an older age," Kremchek said. "The adaptation and anatomic changes around the shoulder are significant and can mold to a thrower's shoulder.

"A lot of times Latin American kids have great arms but never pitched until 17, 18, 19 years old, and they have a higher tendency of injury."

All of this information instructs how the Reds handle young pitchers and even trickles into decisions of whom they draft. Kremchek said he reviews every prospect's medical history. He, Price, many of the organization's minor league pitching coaches and front office staff collaborate in deciding on a case-by-case basis whether an amateur with high-risk mechanics would be worth drafting. They weigh whether changing his mechanics would lessen his performance or if it's worth leaving him alone in hope that his unorthodox delivery isn't a risky one.

When it comes to the pitchers on staff, "we're very proactive," Kremchek said of the Reds' preventive care.

Price classified the organization's minor league pitch-count limits as "strict" but said that he'd like the major league staff to go deeper into games -- "Even if the starter's going six, the game doesn't shorten to seven," he quipped -- which would require preparation at the early levels of the minor leagues. He said that farm systems have perhaps become "too democratic" and that more attention (and more innings) should be allotted to the star prospects more likely ticketed to the majors.

"I want to go back to the days where we have guys on your staff with 10 or 15 complete games and go 250 innings if they're your horse," Price said, "but you can't take them from Point A to Point Z without going through the rest of the alphabet to get there."

And while naturally healthy pitchers will always be sought first, the high rate of success with Tommy John allows the Reds to take calculated risks. Last offseason they signed former Angels reliever Jose Arredondo, who went 10-2 with a 1.62 ERA in 61 innings in 2008, despite knowing that he needed Tommy John.

Before Lehr, a 33-year-old right-hander with only 148 1/3 career big-league innings, went under the knife in May 2010, he called Reds general manager Walt Jocketty and explained that it would be harder to return from a major procedure without support from the club in rehab. Lehr, who had gone 5-3 with a 5.37 ERA in 11 major league starts in 2009 (among 42 total starts including Triple-A and winter ball), provided helpful depth, and he said that Jocketty gave him verbal assurance that he would be brought back. While rehabbing, Lehr also assisted with the player development office.

Now Lehr is a week away from pitching in spring-training games and said that his arm feels great. If anything, he regrets not having the operation sooner. Of his 2009, he said, "I was at an alltime low as far as my stuff goes -- I won games with nothing."

Knowing that pitchers have a strong chance to perform at a high level, however, does not equate to instant success. Though the physical act of recovery is often about one year, Tommy John surgery is often described as a two-year injury because of the mental hurdles that a pitcher must clear to regain confidence in his arm.

Volquez's return to the majors wasn't smooth. After making eight starts with the Reds in July and August, averaging only 4 1/3 innings per outing and sporting a 6.10 ERA, the club sent him down to Triple A for two weeks at the end of August to work out some kinks and refocus his efforts. He had a 1.95 ERA in four starts upon his return, logging nearly seven innings per turn and averaging more than a strikeout per inning.

"When he came back last year, I thought he was really focusing on the velocity aspect of the game, and his mechanics suffered because of it," Price said. "He got to the point where he came up [to the majors] and pitched, but we sent him back to make a couple of starts in Dayton. He came back with a better understanding of where we wanted him to go with his delivery."

The radar gun, while entertaining for fans and the source of the awe-inspiring 105-mph fastball released from the left arm of Chapman last year, can be detrimental to pitchers. Price acknowledges that it can help some pitchers keep an eye on the speed separation of their fastball and offspeed pitches, but mostly it can mess with a hurler's mechanics, as he strains to throw blazing fastballs rather than pitch strikes.

Kremchek's distaste for the gun goes even farther. "I think the radar gun, especially for the young guys, is horrible because they pitch to the gun," he said. "These guys are revving up maybe when they shouldn't in order to hit a certain speed."

But Kremchek understands a young pitcher's motivation because a guy with a 92-mph fastball is roughly average, while a fastball that reaches 95 can signal to scouts that they may have discovered a phenom.

And it is that pursuit of the next great thing that will surely push the arms of young pitchers to the brink again and again. That won't ever stop, but some clubs, like the Reds, are doing their best to improve their odds.