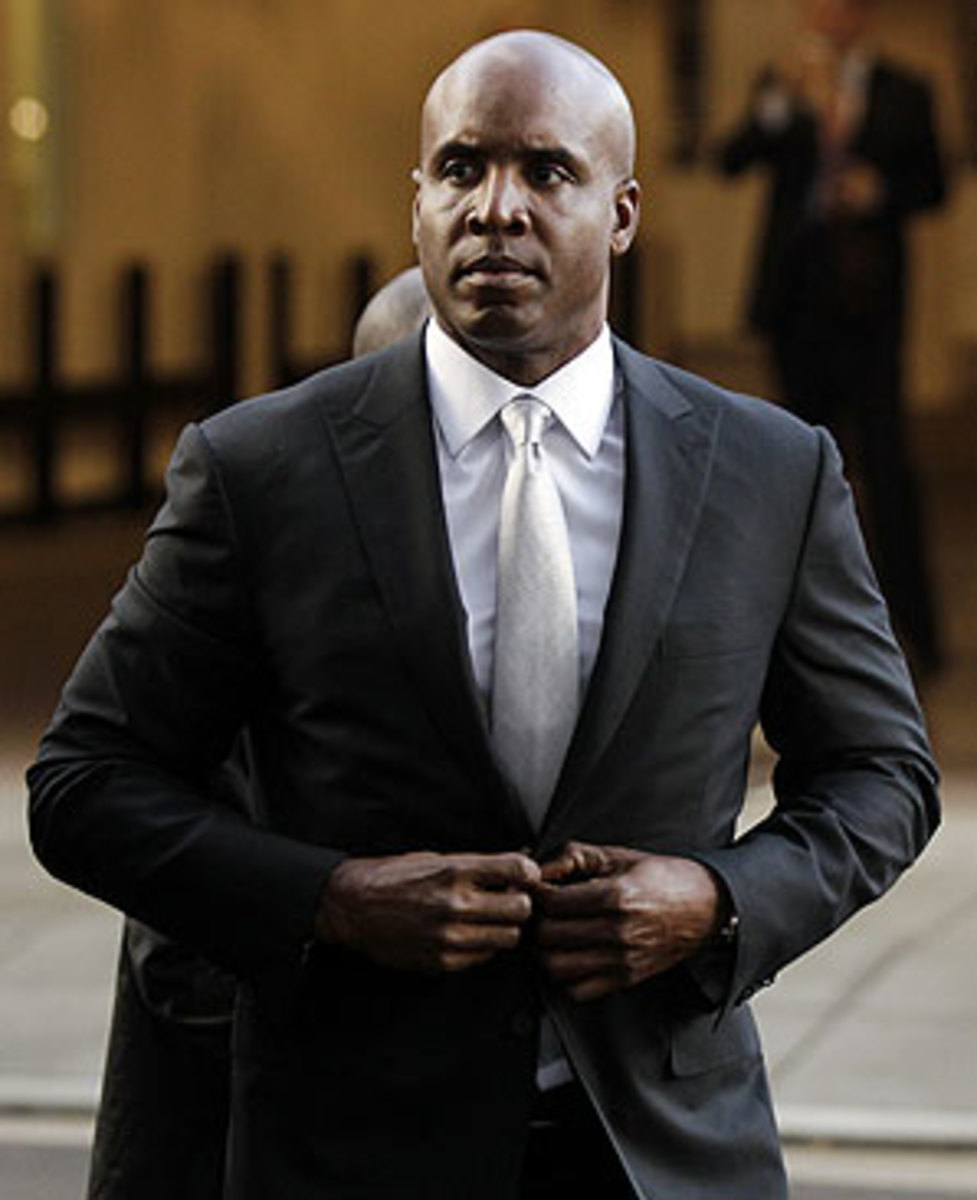

Bonds' trial not about home run king or his tarnished legacy

The all-time home run leader is on trial in criminal court. What sounds like an explosive trial is, from a baseball perspective, oddly lacking in meaning. The United States of America vs. Barry Lamar Bonds, case 07-0732, has almost nothing to do with the legacy of the home run king. That acquired an indelible stain long ago.

This is about the gamesmanship of big-time lawyering and little more. This is about Matthew Parella and Jeff Nedrow and Allen Ruby and Dennis Riordan and the rest of the suits who have more at stake than Bonds as far as reputations go.

For Bonds, there is no reputation as a ballplayer left to save, no chance for "vindication" of his tainted career. The trial never was about whether a world-class athlete turned to one of the most sophisticated doping regimens ever known to lay waste to major league pitching, sportsmanship and the veracity of the record book. It was about whether he lied when he told a grand jury he didn't know those were steroids he systematically was taking to get fairly unbelievable results.

The prosecution has to prove beyond a doubt to 12 jurors that Bonds lied. It is an uphill climb without the cooperation and logbooks of his trainer, Greg Anderson, and with a grand jury transcript of a wily Bonds that hardly stands as a primer on airtight questioning. Prosecutors risk embarrassment, if it doesn't exist already, that they chased Bonds for eight years, overspent their time and resources and failed to prove something most everybody considers true and has little meaningful social import anyway.

There are two likely outcomes for Bonds. One, he is convicted of perjury and probably gets sentenced to house arrest or a few months in prison and is consigned to history as an all-time great player with fraudulence attached to his playing record. Two, he is found not guilty of perjury and is consigned to history as an all-time great player with fraudulence attached to his playing record.

"This record is not tainted at all. Period," Bonds barked upon breaking the career record of home runs that belonged to Hank Aaron.

It is as empty a statement today as it was then, in 2007.

The Dr. Frankensteins at BALCO were very good at what they did, their designer drugs transforming the way athletes looked and performed, all under the unofficial motto of "We Pass All Drug Tests (Re-testing once our juice is discovered is excluded)."

Bonds was a star pupil. In Bonds, the schemers at the BALCO lab began with the advantage of someone who already was at the upper end of elite talent. Through his age 34 season, Bonds was almost as good as Ken Griffey Jr. at the same age:

What happened from there, however, was nothing short of freakish. Here is where Bonds and Griffey diverged:

Wait. Even that doesn't explain best how Bonds took his game to an unprecedented level. It is better to compare Bonds at ages 35 through 39 to Griffey in his prime years when he was 10 years younger, ages 25-29:

Try to let that sink in. Bonds became a far better hitter as he was approaching 40 years old than Griffey -- one of the all-time great players - was in the prime of his youth.

Flaxseed oil and arthritic balm, dude, is how he explained it to the jury.

Bonds didn't merely stop his baseball clock as he aged, he turned it back like nothing ever seen before. The dog days of August for an aging player? Didn't apply to him. While other older guys switched to lighter bats, needed more days off and saw their numbers reduced by age and the grind of the long season, Bonds never had a bad day with BALCO's magic potions.

Here are his August batting averages from ages 35 through 39: .333, .350, .447, .452, .414. In those five seasons combined as he approached 40 years old, Bonds hit .370 in August and September while averaging one home run every 7.8 at-bats -- an eight percent increase in his home run rate the longer the season went.

All of this is nothing new. This appraisal of the BALCO Bonds is just another perspective of the incomprehensible, like the unnatural world's equivalent of switching rims to view the Grand Canyon. Likewise, there is nothing new about the trial. We've heard it all before. The obdurate silence of Anderson, the parade of steroid-addled BALCO clients, the shrinking of the testicles and the growth of the feet and head, the pillow talk of the mistress . . . is there any embarrassment possibly left?

Bonds is not expected to testify, so there is no drama even in his appearance. Nedrow, one of the prosecutors, said in court he expected the trial to take only two weeks -- given the Monday through Thursday court schedule, just eight sessions. Ruby, Bonds' lead attorney, suggested in court it would take longer because of cross-examinations. The judge, Susan Illston, said, "I have -- effectively, we have a month to do it."

The courtroom is a long way from the ballpark and the record book. If someone tries to tell you the baseball legacy of Bonds rides on this trial, go ahead and laugh. His freedom? His rights as a citizen? Perhaps. But the outcome changes nothing about the established facts of the ballplayer he was and the choices he made.

These two to four weeks are about the suits, the ones who pursued Bonds with a noticeable relentlessness and the ones who will defend him with the tenacity to match. It's not about baseball. It's about what happens when the law becomes wet clay, and what the lawyers can make of it. Their reputations are the ones still in play.