Between youth and adulthood, covering the '89 Giants

SI.com asked several current and retired SI writers to offer reflections on the best team they ever covered as sports journalists. Here's S.L. Price on the 1989 San Francisco Giants:

First, there was the bridge. I would hit it around 4 p.m., with the sun blazing, the sky so summery that you thought, no, not tonight: There's no way that the wind and fog will roll in again, turn July into November and make Candlestick Park colder than a meat locker. I rode a beat-up Vespa because it was cheap and you could park on the sidewalk, never risking a ticket, and feel each time that you'd pulled one over on parking-starved San Francisco. Beat the system in a strange city, and it loses its power to awe. Do that a few times, and the place begins to feel like home.

Still that bridge. I'd zip down Market St., make my way over to Third, and then hit the Lefty O'Doul drawbridge, tires feeling about as sturdy as Cheerios on the shimmery surface, that massive concrete counterweight hovering overhead like a threat. These days, of course, the O'Doul Bridge squats like an outdated hulk of lawn furniture next to streamlined AT & T Park. Back then, though, it was the insider's gateway not just to The 'Stick and its dicey home neighborhood of Hunter's Point, but into San Francisco's baseball past. Lefty O'Doul, native son, had managed the Pacific Coast League Seals in the 1930s and handled the DiMaggio brothers, then later opened the best bar in town. A bridge named for a drinking baseball man? Perfect.

The task here is to detail the best team I ever covered. On the face of it, choosing the 1989 San Francisco Giants makes little sense. By then I'd already covered a North Carolina basketball team featuring Michael Jordan, Sam Perkins and Brad Daugherty and the inaugural season of the Sacramento Kings; in months I would cover a Super Bowl blowout won by Joe Montana's incomparable 49ers. Across the Bay, the flamboyant A's -- all Bash Brothers and La Russa and Eck -- were making headlines and, it seemed, a dynasty; they crushed those '89 Giants in the World Series with a four-game sweep. Besides, I was covering the Bay Area for an oddly named newspaper, The Sacramento Bee, based in a city 90 miles away. I uncovered no malfeasance, sparked no controversy. Not one Giants story I wrote had impact.

But I was 27 in 1989, and if I'm being honest that explains much of why that year resonates still. Joseph Conrad deemed such an age the "shadow-line" between youth and adulthood and, though I didn't know it then, I had learned some things. For example, if former San Diego gangbanger Kevin Mitchell, standing naked but for a pair of leopard-print briefs, squints in puzzlement at some dumb question you ask, don't press matters. If cackling country boy Will Clark wants to declare, "I know who you are! I know EXACTLY who you are" don't tell him that his bullyboy schtick comes off more comical than menacing. If pitcher Mike Krukow demands a specific bottle of fine red to exclusively review Bull Durham, buy him two -- and make sure to expense it. And if gerbil-headed coach Don Zimmer explodes in a barely-dressed, spit-filled rage at no one in particular, stare at the wall as if musing about the prospects of interplanetary travel, because this, too, shall pass.

SI VAULT: When the World Series became a modest sporting event (10.30.89), by Ron Fimrite

I had been reporting for five years, yet still didn't know how to work a locker room or sources, or the very basics of the English language on deadline. I was that most ridiculous of figures -- someone in love with the idea of being a writer without being able to write -- but with the Giants that year, something clicked. Part of it was the unusually welcoming cadre of Bay Area media, but most was due to the contagious cowboy manner of manager Roger Craig: low-key, unparanoid, lacking any kiss-the-ring reverence. Clark had calmed some, Zimmer was gone. Staff ace Rick "Big Daddy" Reuschel was, simply, the most aggressively boring man in history, and the glint in his eye during his press scrum told you that he knew it, he knew you knew it, so, guys, can we all just end the nonsense and get out of here already?

Really, no locker room since has ever felt quite so adult, and somewhere in that mature, relaxed space I hit a stride, figured out how to cover a ballclub for the first time. Living downtown, too, I could finally sense, pick apart, the symbiosis between fan, city and team; I was living it in a way I never had before or have since, and who knows how much that had to do with winning? Mitchell had himself a career year -- catching a fly ball bare-handed, hitting 47 home runs, winning the MVP -- and Clark single-handedly destroyed the Cubs in the playoffs as both the Giants and A's won the pennant and sent the Bay Area into a baseball frenzy.

Every day felt vital. The papers and radio shows filled the morning air and space with wall-to-wall coverage, and then I'd bomb over to frigid Candlestick, where fog would roll over the lip of the stadium -- to the sound of foghorns -- and spectators wore winter coats in August. It was a place loathed by management and players, a multi-purpose stadium seemingly without soul, and when the '89 World Series moved there for Game 3, with the A's leading two games to none, few were expecting it to be anything more than a benign backdrop.

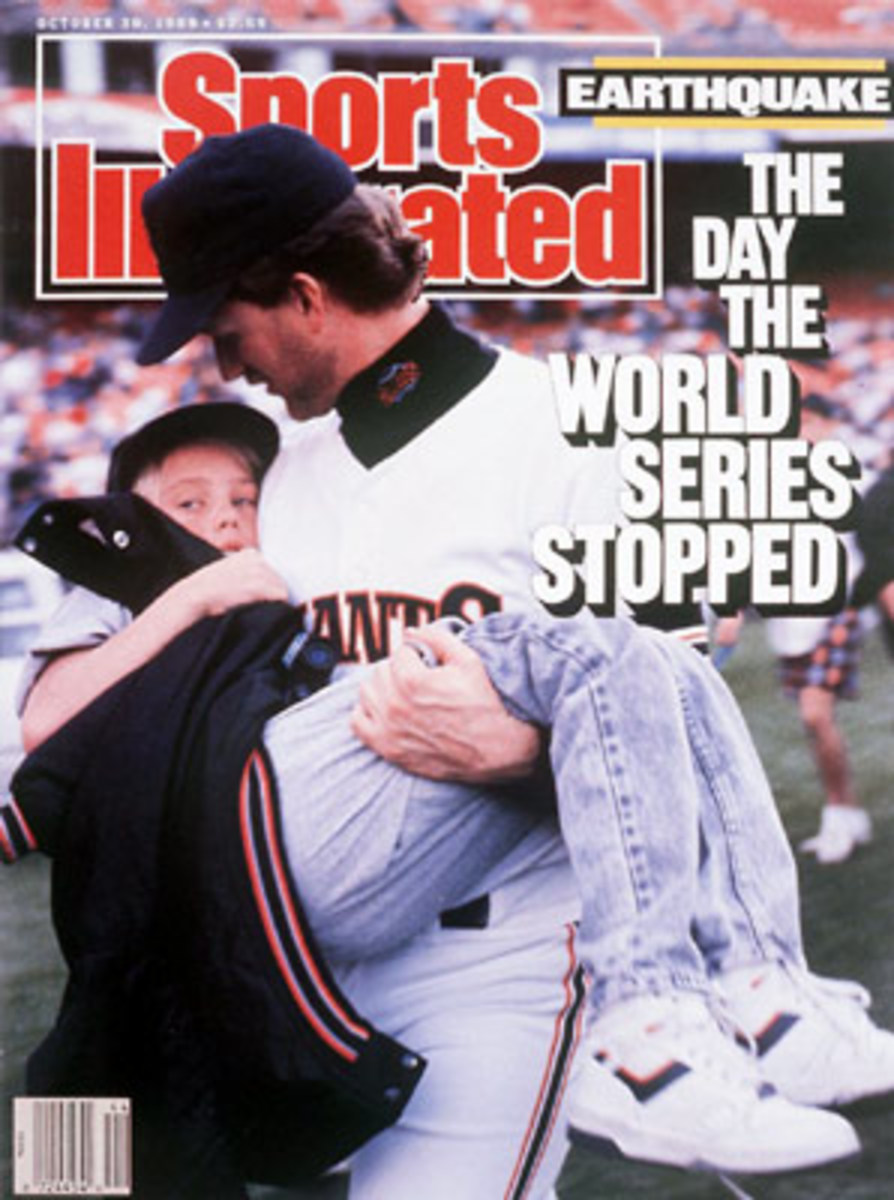

At 5:04 p.m., while the players were warming up, a magnitude 7.1 earthquake struck just south of the city. Buildings crumbled, especially those built upon landfill liquefied by the temblor; a section of the Bay Bridge dropped and killed one; a double-decker highway in Oakland pancaked, killing 42. I was sitting in the upper deck of Candlestick, typing notes. It felt as if the entire structure, a stadium teeming with tens of thousands of people, had suddenly jumped. There was a banging, screams. The lights flickered out.

But the upper deck didn't drop. Candlestick Park, built on bedrock, held firm and became, then and forever, my favorite structure on earth.

I didn't hesitate. The story wasn't up in the stands; the players -- and the safest place to be -- were all down on the field. I grabbed my pad, raced down the steps, through the portal filling with panic, down a series of ramps and then out into the grass. A's outfielder Rickey Henderson, raised in Oakland, begged a fan with a TV for any news. "The Bay Bridge is down?" he said.

I wrote it all down. I typed it up later, in the backseat of a car riding through pitch-black streets. And I was hardly alone. Sportswriters from all over the country became news reporters in the minutes and hours after and during the 10-day break that followed; it was the biggest story in the land. We visited disaster zones. We talked to the homeless. We typed on sidewalks, in bars, and we didn't embarrass ourselves once.

I didn't know it then, but soon I would be leaving the city for good. There would be other assignments, some frightening -- a soccer riot in Italy, a hurricane, the soccer-drug connection in Colombia, a car crash in Cuba. But that year, that day, made me ready for all that. For the first time, I realized that I might just survive.