Hoops giant Sabonis was a mystery man with indisputable talent

"Is this all for you?" I jokingly asked Vlade Divac, the personable Yugoslavian center who played 16 seasons for the Hornets, Lakers and Kings.

"No, no," he said, waving his arms and pointing. "It's for the Big Man."

Divac is himself 7-foot-1, but at that moment I understood. Into the ring of people strode Arvydas Sabonis, 7-3 and -- I'm guessing here -- 330 pounds, maybe 20 more than his final NBA playing weight and maybe 75 pounds more than his weight in the early 1980s when Sabonis was widely described as -- get ready -- The Best Player in the World.

Sabonis will take his rightful place in the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame on Friday night. American fans will recognize him mainly as the plodding behemoth who patrolled the pivot for the Portland Trail Blazers of the mid- and late-1990s. But he was -- and should be recognized as -- so much more.

Sabonis is an eternal mystery man, the guy you heard so much about but never saw until it was too late. The American prototype is the big-city playground star who, because of some combination of drugs, alcohol, misdeeds and bad karma, either never reaches the big-time or gets there only when age and injuries have caught up to him. (Think Connie Hawkins, unfairly black-balled by the college betting scandals.) Sabonis is the international version, an extraordinary talent who was victimized by a repressive Soviet system that made him a virtual prisoner during his best years and turned him into rather the basketball version of Sasquatch: On those rare occasions when he was spotted, he was either outsmarting his rivals or stomping on them.

The basketball world first started to hear about this mysterious Lithuanian giant in the early 1980s when Sabonis, who was born in 1964, was still a teenager. Touring teams would invariably be amazed at the skill, dexterity and basketball IQ of the young giant. I didn't see him those early years, but one who bore witness was Sports Illustrated colleague Alexander Wolff, this year's winner of the Curt Gowdy Media Award. Here is Alex's account:

"I saw him in 1984, during the European pre-Olympic tournament in a little French provincial town, Saint-Quentin, where the Soviets were mopping up in the prelims, and again at Bercy, in Paris, where they dispatched everyone in what was a moot exercise, on account of the not-yet-announced Olympic boycott.

"Sabonis was breathtaking. The three things that struck me were, first, his outlet passes. With what seemed like hardly any effort, the ball would just materialize in a guard's hands around midcourt. No effort at all. Second, his outside touch. Finally, he was perfectly proportioned -- a normal human being simply writ large." Then Wolff added: "Oh, and he was 19 at the time."

Indeed, there was none of the Erector-Set awkwardness that was associated with European players back then. He was the real deal. Teams with sophisticated scouting departments wanted him but drafting foreign players was a dicey proposition. And drafting Soviet players -- there was no telling who you had to pay off and whether the authorities would let the player come anyway -- was even dicier. The Hawks took the plunge on Sabonis in 1985, but there was no chance that he was coming then while the Cold War was still going on. Anyway, the pick was voided because he was under 21, the prevailing rule at the time. The Trail Blazers eventually won the unpredictable Sabonis stakes, but he didn't arrive until 1995, nine years after Portland drafted him, when he was 31 and hobbled by foot problems (his Achilles tendon had been repaired and he had arthritic feet) of the Bill Walton dimension. (Walton, whom Sabonis idolized as a player, will be standing up for him at Friday's ceremonies.)

Sabonis' personality added to his sense of mystery. He was by most accounts an intelligent man with a great sense of humor but wasn't much interested in communicating with the Western world and used the language barrier as his defense mechanism. "He knew much more English than he let on," his Lithuanian teammate Sarunas Marciulionis told me. Sabonis lacked the diplomatic skills and temperament of a Marciulionis or a Divac, both of whom were unfailingly charming when dealing with the Western world. The top-flight Soviet players all had reason to be bitter, and Sabonis, the best of them, seemed to be more bitter than most.

Eventually, he developed more than a passing relationship with a bottle of vodka, a condition that former SI writer Curry Kirkpatrick memorably labeled as "Stolichnaya elbow." That sounds like the most groaningly obvious stereotype, the stolid Eastern Bloc-er pickling himself with the national drink, but that doesn't mean it isn't true. I heard the same priceless Sabonis/vodka story from both Marciulionis and Dallas Mavericks general manager Donnie Nelson, who was an assistant coach on the Lithuanian team that won a bronze medal at the 1992 Barcelona Olympics.

After the Lithuanians defeated the Unified team for the bronze -- a victory fraught with meaning since the Unifieds represented, to the Lithuanians, the very Soviet empire against which they had fought for their independence -- the closing ceremonies were still hours away. "That's far too much time for a Lithuanian," Nelson told me, smiling. Sabonis drank so prodigiously in his postgame celebration that he was unable to roust himself for the appearance on the medal stand and was later found spreading his own version of Glasnost in the dorm of the Russian women's Olympic team.

Sabonis' drinking is part of his legend, as is his skill, his dark past, his wasted years and his imperviousness to pain. In a column he wrote for The Oregonian, Jason Quick elicited this immortal quote from Blazers team physician Don Roberts, who was shocked when he got Sabonis' medical records: "The X-ray alone would get you a handicap parking permit," Roberts said.

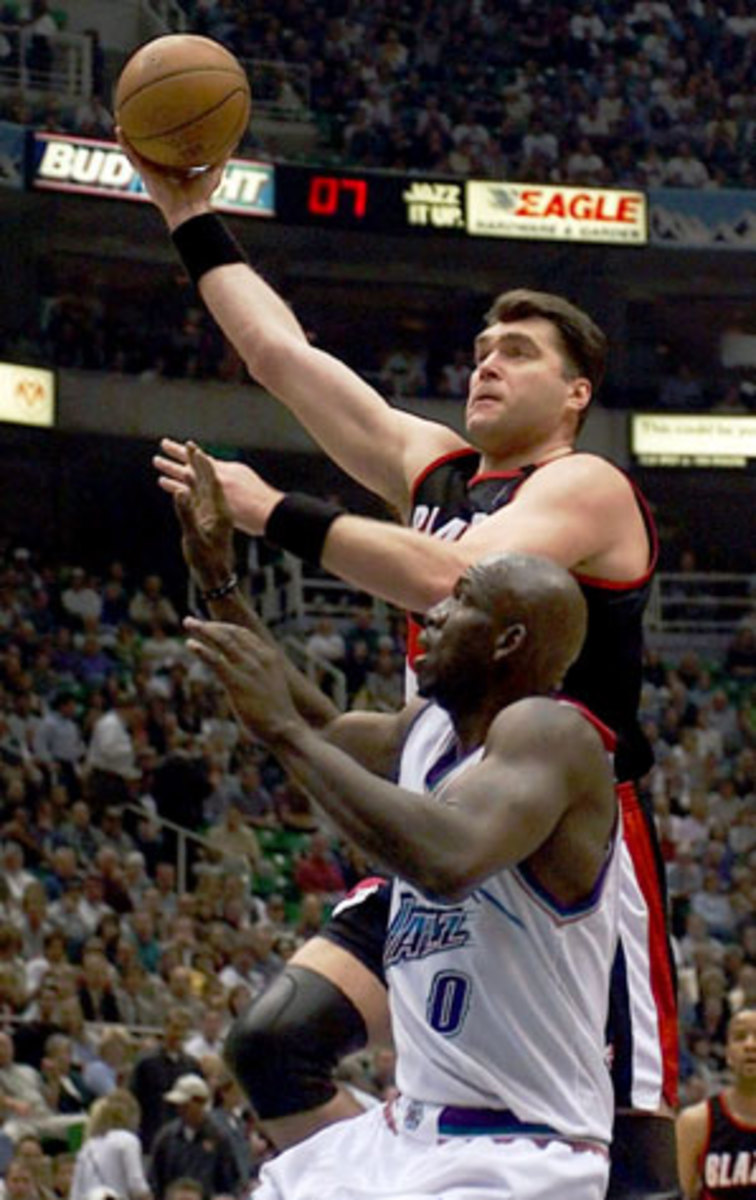

But Sabonis still managed seven fairly productive seasons in Portland when he was, oh, maybe 30 percent of what he once was. (In five 1996 playoff games against the Utah Jazz, he averaged 23.6 points and 10.2 rebounds, an indicator of what he could've been.)

Perhaps, in his acceptance speech Friday (which I assume will be translated), he will reveal something of the personal anguish he suffered because of his lost years. I doubt it -- to the extent that I knew him, he never seemed like a guy prone to self-pity -- and in a way I hope he doesn't. I like the Sabonis of eternal mystery. But never doubt that he truly belongs among the game's greats.