Check the sky for pigs: NCAA's APR ruling the result of common sense

I never dreamed I'd write the following sentence, but for the first time in the decade-plus I've been covering college sports, it's absolutely true: The NCAA is listening.

Seriously.

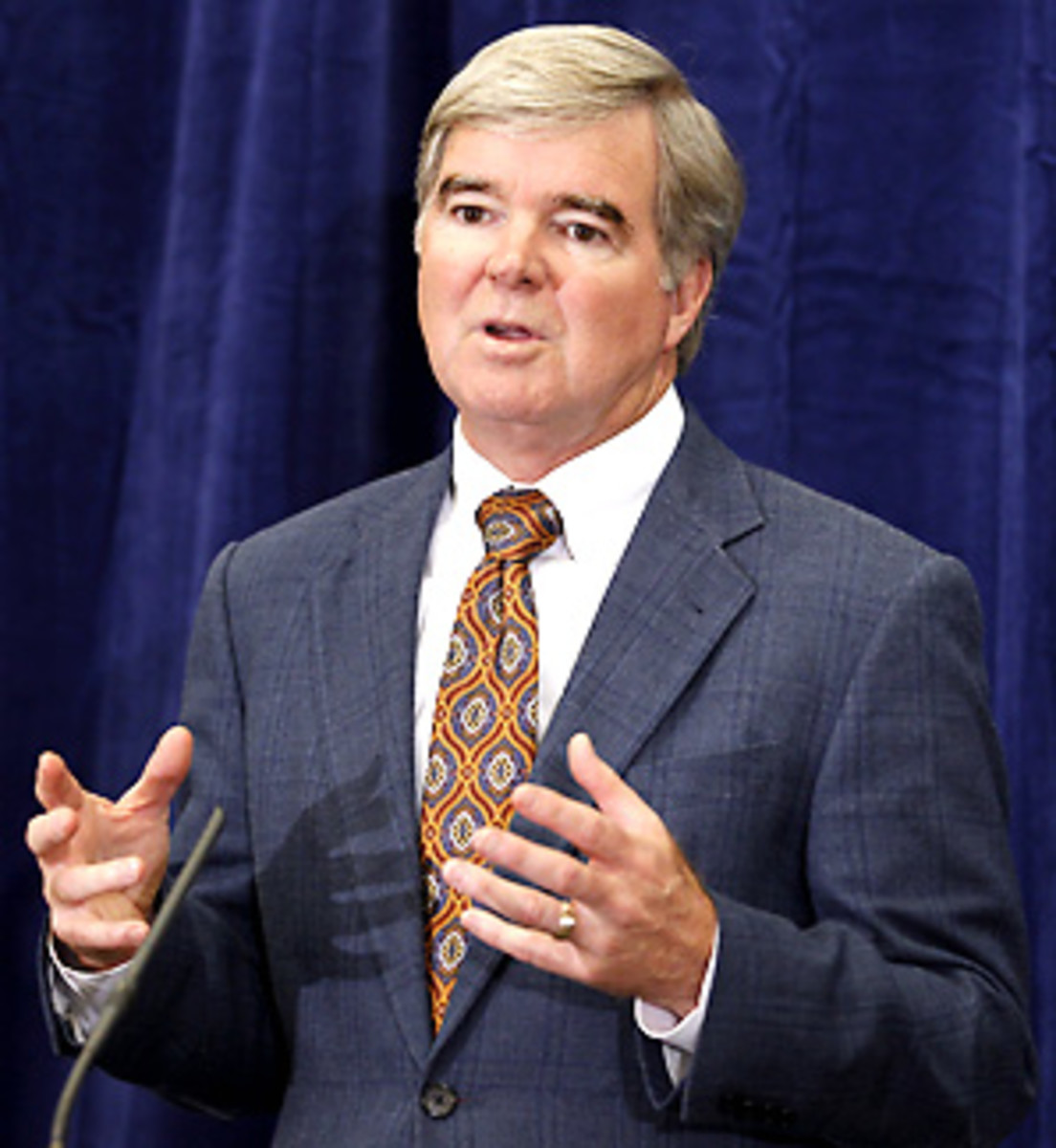

On Tuesday and Wednesday, Mark Emmert held a highly publicized retreat for 50 university presidents and chancellors, purportedly to discuss "systemic change" to address various hot-button issues in college sports. Naturally, I assumed this meant the formation of more subcommittees and task forces.

Instead, the presidents at Wednesday's wrap-up press conference all spoke strongly and with an unusual amount of specificity about promising quick and decisive action over the coming year. Naturally, I assumed this meant sending a bunch of proposals through the NCAA legislative vortex and watching them get sliced and diced until barely recognizable.

Wrong again.

Less than 24 hours later, the Division I Board of Directors had already approved one of the most significant proposals to come out of this week's discussions: banning teams that don't garner a four-year APR (Academic Progress Rate) score of 930 (roughly equivalent to a 50 percent graduation rate) from the postseason -- including bowl games and March Madness.

How significant is that number? Twelve of last year's tourney teams -- including No. 1 seed Ohio State -- would have been ineligible had that standard been in effect.

The NCAA didn't stop there. You know that swirling controversy over ESPN's new Longhorn Network attempting to televise high school games? The board took care of that too. "The current bylaws do not support youth programming on collegiate networks," declared USF president and board chair Judy Genshaft.

The NCAA never acts this quickly on anything -- aside from Ohio State players' bowl eligibility, of course. Cheap joke aside, it appears the Buckeyes' much-chronicled troubles -- along with those of Cecil Newton, Bruce Pearl, Willie Lyles and every other high-profile headliner who's put a blight on the landscape over the past year -- prompted the unprecedented sense of urgency that suddenly swept through Indianapolis this week.

"Presidents are fed up with the rule breaking that is out there," said Penn State President Graham Spanier. "... Some of these things, our coaches and our boosters might not like, but we need to do what I think you are going to see happen in the next year."

Based on comments made this week, and Thursday's evidence that these things really can come to fruition, we should expect major changes in three other areas over the next six to nine months:

• An overhaul of the current enforcement process. Emmert and the presidents spoke universally of a desire to cut down on the many "nuisance rules" (free lunches, text-message limits, etc.) that take up an inordinate amount of compliance officers' time while beefing up penalties for deliberate, egregious rules violations. This will likely include expanding the classifications for infractions from the current and vague duo of "major" and "secondary."

• Allowing individual conferences, if they so choose, to implement full cost-of-attendance scholarships (as Big Ten Commissioner Jim Delany first pushed for last spring) and/or multiyear scholarships. The obvious implication is that only the richest conferences could afford to do so, which in traditional NCAA parlance represents dreaded "competitive equity" issues. But the presidents seem to be lock-step with the commissioners in believing said imbalance already exists.

• Raising initial academic eligibility standards both for high school seniors and juco transfers. No specifics were offered, but they could be along the lines of SEC commissioner Mike Slive's proposal to increase incoming students' minimum core GPA from 2.0 to 2.5.

No, this isn't the complete system revolt the NCAA's harshest critics would like to see. But by NCAA standards, these are unquestionably major changes. And somehow, it only took two days to agree to them.

"The retreat was one of the most important events the NCAA has had in many, many years," said Genshaft.

The most tangible change so far, the postseason APR requirement, is sure to be met with controversy. The new standard won't take full effect for three to five years (the board asked for a proposal by October that will outline a timeline for phasing in the new cutoff score, currently 30 points lower), but the APR has never been a big hit with major hoops coaches, many of whose scores suffer when a rash of players let their grades slide shortly before bolting for the pros. It's also inherently unfair to underfunded, smaller-conference programs that can't afford to build opulent academic centers and load them up with tutors. Under the 930 standard, the SWAC would have had just one team (Alcorn State) eligible for last season's tourney.

Conversely, the SEC would have qualified all 12 teams for bowl games this season -- despite its perception for not being big in the brains department. (Six BCS-conference schools missed the cut in 2010: Colorado, Louisville, Maryland, Michigan, NC State and Washington State.)

The presidents on Thursday's conference call seemed empathetic to the plight of the SWAC's Historically Black Colleges, but not so much to the challenges facing Jim Boeheim or Jim Calhoun and their bands of semipros.

"This is all about making sure student athletes are students," said Emmert. "[It's] about making sure they behave accordingly."

Hopefully the academic folks can find a way to work out the kinks in the APR during this so-called ramp-up period, because in theory, this kind of initative is exactly what the NCAA should be doing. If you're going to claim, as the NCAA does in all its advertisements, that athletics are an extension of academics, then of course there should be some sort of academic requirement to participate in tournaments. It's just common sense.

And really, that's the shared theme of all the reforms being proposed by the presidents. Common sense says they should deregulate that bloated rule book. Common sense says the Pac-12 can afford to dole out some of that $3 billion in TV money to its athletes without going bankrupt. Many of us have been writing and saying this for years (and groups like the Knight Commission have been proposing some of these very things for a decade), but for whatever reason, common sense never seemed to be a driving factor in the NCAA legislative process -- until this week.

It's unfortunate that it took a rash of scandals to motivate the presidents to take action, but the important thing is that they're doing it -- and doing it quickly. NCAA legislation often takes so long to wind its way through the meat grinder that by the time a bill becomes law, the issue it addressed is already outdated. But if the proposed changes really do come to pass within the presidents' stated timeline, it will go down as one of the swiftest responses to crisis in the organization's history. And in the case of The Longhorn Network, the Board of Directors actually acted in real time.

I don't know whether to pat the board members on the back for their decisiveness or to check the sky for flying pigs. Neither seemed plausible as recently as Monday.