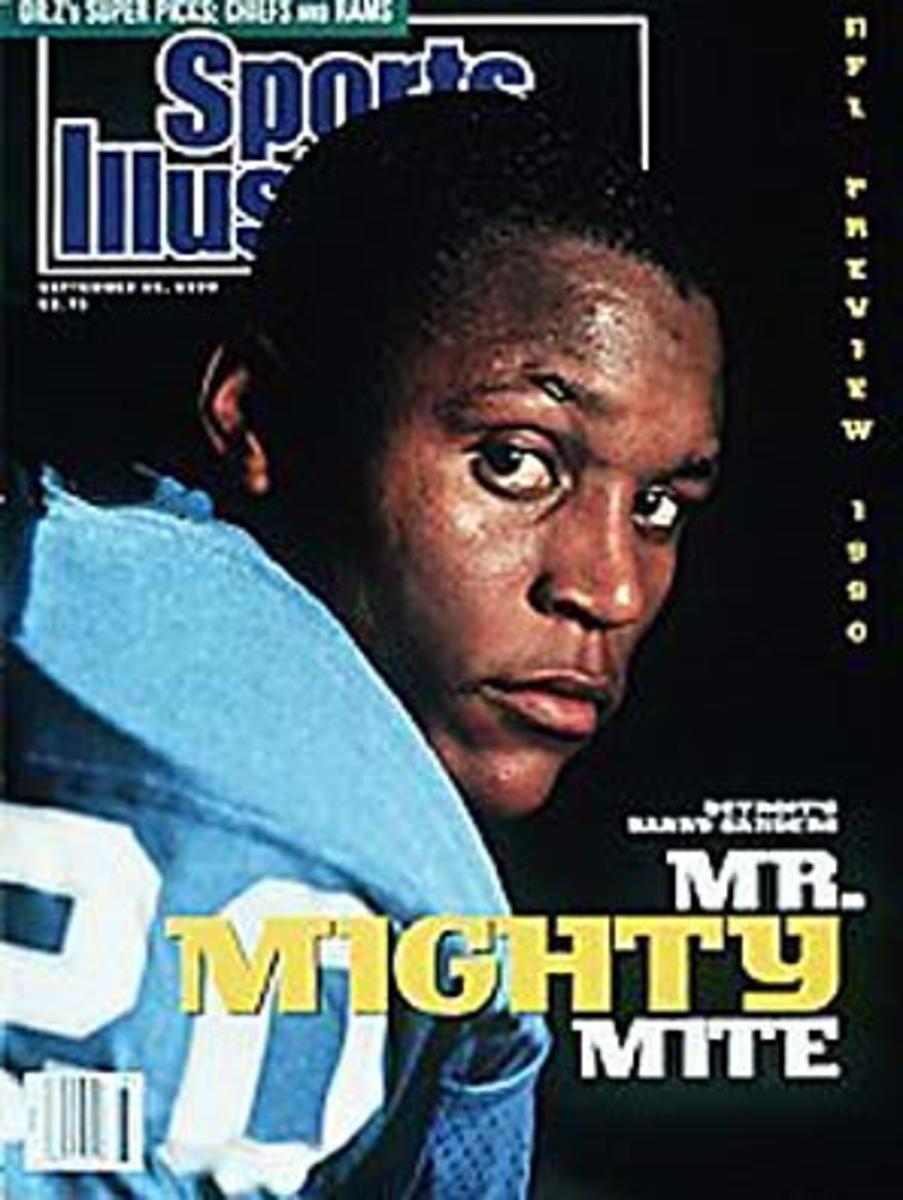

One of the greatest Lions of all has high hopes for the current team

The Detroit Lions are back in the headlines, and in his own understated way, so is Barry Sanders. He still watches the team he used to run so hard for, the team he made relevant even when the Lions were duds, the team he left abruptly after 10 seasons.

"For me, it was mostly just time to leave," Sanders said by telephone Thursday from Wichita, Kan., where he was speaking at his old high school, Wichita North. "I had a great run and it was just time to move on."

Sanders, 43, was being honored Thursday as part of the Hometown Hall of Famer presented by the Pro Football Hall of Fame and Allstate, a program where NFL legends are celebrated in the cities where they grew up. Many of the students in Sanders' audience were too young to remember his electrifying play in the Lions' backfield ("Most of them don't know who I am," Sanders said laughing), but he didn't mind sharing some life lessons.

Even 13 years after his final NFL carry, Sanders's career evokes wonderment and respect, but also a wistfulness in those who watched him scamper in the old Pontiac Silverdome. Many wish he could have played in a Super Bowl. Many wish he could have scampered just a few seasons more.

All these years later, he is still asked why he retired at 30, why he walked away from the game after rushing for 1,491 yards in 1998, his final season.

"I definitely felt like, as far as the team, that we were kind of going downhill," Sanders said of a Lions team that went 5-11 after going 9-7 the previous year. "But in addition to that, it was also about that internal flame and the desire to continue to play."

Few doubt that Sanders could have continued to be a great running back (he was 1,457 yards short of Walter Payton's career rushing record), but he also walked away with his dignity and his health. Even in the statement he released at his retirement, Sanders was to the point: "My desire to exit the game is greater than my desire to remain in it," he said.

When he left football, Sanders went into the banking business, opened up a car dealership in Stillwater, Okla., and mostly stayed on the fringes of the NFL. While many athletes struggle to find fulfillment in their post-playing careers -- a point emphasized in Jeff Pearlman's biography of Payton -- Sanders says he has not.

"One of the things I realized, even before I retired, was that it's not like you're going to stumble across something like pro football as exciting and fun, or that you're going to get paid as much," Sanders said. "It's an adjustment. But for me I was looking forward to not playing football."

He still followed the game, though, watching the Lions and their dismal drafts and dormant seasons until their recent surge under head coach Jim Schwartz and general manager Martin Mayhew.

Asked if he was bothered by Schwartz's style, or the Lions trying to channel the 1980s Detroit Pistons, Sanders laughed. "We love him there," he said. "Bottom line is, he knows how to win and he cares about winning. He's going to get the best out of his players. Coach Schwartz has changed the culture."

Sanders went on to praise the Lions' front office.

"For years we had a pretty bad record of some draft picks that did not work out, without naming names, guys that couldn't help anybody," Sanders said. "Now we're seeing guys who can be perennial Pro Bowl players. Pro football isn't an exact science, but there is a reason certain teams win and certain tams rebuild. Look where Green Bay is after tough decision of getting rid of Brett Favre, or a team like Philadelphia that wins consistently. We have a pretty good formula now."

Last Monday night, Sanders was in front of the television watching the Jaguars and Ravens, finding beauty in a low-scoring slugfest.

"I enjoy watching Ray Lewis and Maurice Jones-Drew -- I knew that would be a big clash," said Sanders, adding Adrian Peterson, Tom Brady and Carolina's Steve Smith to the list of players that pull him to the TV.

And with that, it was time for Sanders to go speak to some of Wichita's young people on the cusp of their own dreams. He said goodbye. The phone line went dead. Barry Sanders was gone.