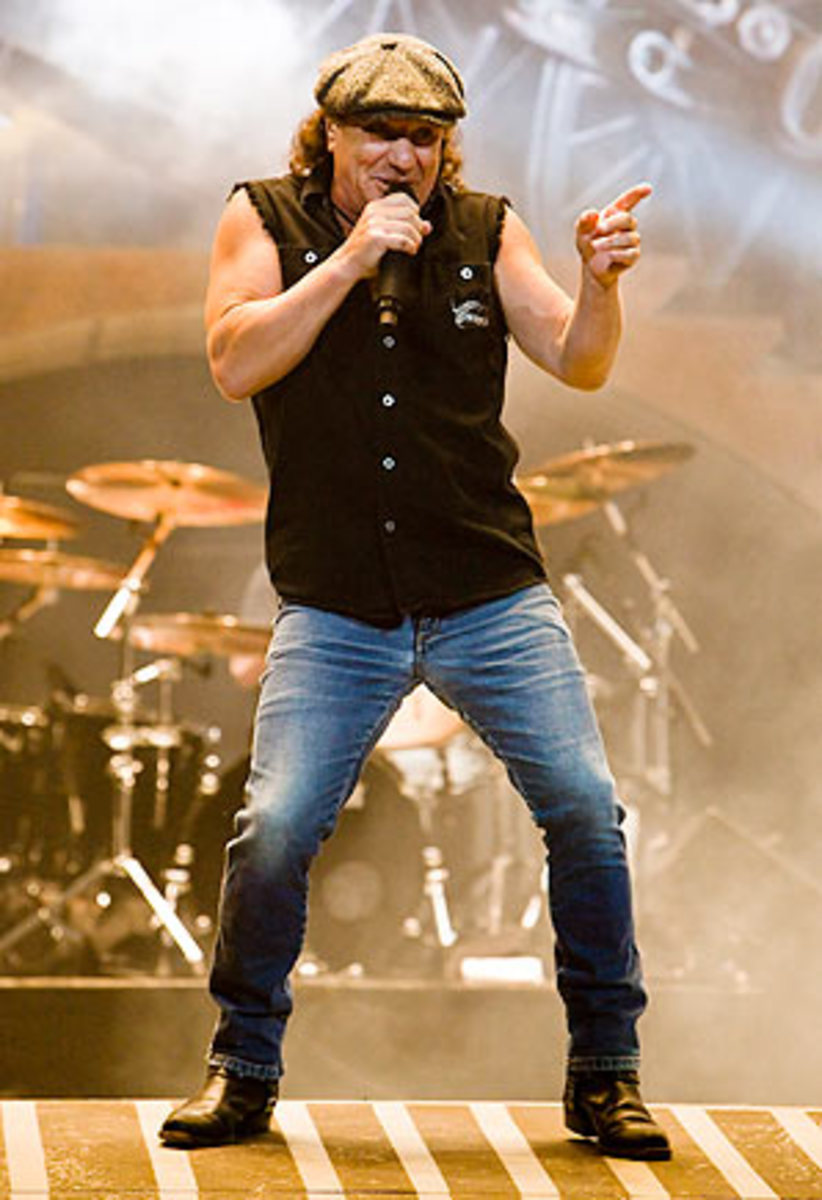

AC/DC frontman Brian Johnson takes to the track to aid charity

"There she is. This is the star of the show," said Johnson, the 64-year-old lead singer of the rock group AC/DC and beginning on this December day, a NASCAR driver preparing for his first Grand-Am Series Rolex 24. "I just have to try and keep her in one piece."

Grinning profusely as he turned to his teammates and a small group of onlookers that had come to see this spectacle of Rock and Roll Hall of Famer turned sports car driver, Johnson noticed an energy drink sticker loosely affixed to his t-shirt.

"Ah!" he carped in mock derision. "I guess I have to thank my f------ sponsor now, too."

Brian Johnson understands scrutiny. He can sense when he is expected to fail. This, after all, is a man chosen to replace Bon Scott -- possessor of one of the most iconic voices and rollicking personalities in hard rock history -- when the lead singer died of acute alcohol poisoning in 1980. With Johnson out front, the already legendary AC/DC returned with Back in Black, which has sold 49 million copies worldwide, second all-time only to Michael Jackson's Thriller. The group, once on the verge of disbanding, catapulted into its next and on-going 30-year incarnation with Johnson. Johnson, from a long line of Newcastle, England coal miners, forged his own identity with his ubiquitous driving cap and a power-tool growl of a voice that still roars from speakers at hockey games, concert halls and wedding receptions. No one, it seems, can resist You Shook Me All Night Long. He has seen or done many things since he joined AC/DC in 1980, and with the latter stages of his music career sorting themselves out to his liking, he's found time for his other passion: cars, and for the last 11 years, racing.

Johnson has won races and stood upon podiums in the Heritage Racing Series in his trusty '65 Lola T70, and some time ago he was approached by part-time Predator Racing teammate and Chattanooga businessman Byron DeFoor about joining him for a project he was putting together for the 24-hour season-opening Grand-Am race at Daytona.

"He asked [if I was interested in joining him], and I said, 'More than anything else in the world'," Johnson remembers. "Being a kid growing up in Europe, it was the 24 hours of Le Mans, the Mille Miglia you just read about in mags and stuff. There were those wonderful images of heroic drivers with goggles and all this kind of thing, [it] stirs the imagination."

Johnson, who still recites the names of those drivers with child-like reverence, learned more about North American endurance racing when he began touring with AC/DC.

"I just always wanted to be part of it, but to actually drive in it, was just ..." he said. "I didn't even have the ability to even mix with these puppies, but after about 12 years of vintage racing, everybody said, 'Come on Brian. Give it a shot. You got a few podiums,' and stuff like that. Byron just made it happen."

The similarities between conducting an arena full of fans and a race car full of horsepower and mayhem are "frightening," Johnson said.

"You have to do them to understand what I'm talking about," he said. "There are very few people who have ever had that unique experience. When you go on stage, you go with four other lads, and in my case I've got four of the greatest guys on the planet to play with, my friends, great lads. [On stage] the flag drops, kind of, and you come out and you start, and it's the same as racing. You can't give too much too early. You can't dive into that first corner. You've got two and a half hours to go. You've got to bring it up and keep it going. You can't just give it all away and have the rest of it be pretty boring. And then it's the same in racing. You can't be a big flurry of arms and fists and fists and arms because you'll end up in the grass, screwed up or whatever. It's a case of using your head."

The logo is emblazoned on the left front side of the No. 50 Dinan-prepared BMW/Riley, just above the wheel well. It's the symbol of the philanthropic mission that makes their endeavor in the 50th Rolex 24 more than just the fulfillment of a sporting dream. Established to benefit the Austin Hatcher Foundation for pediatric cancer research and named -- with a softened twist -- after a pre-Johnson AC/DC smash (Highway to Help), the charity has set a $1 million fundraising goal for the Rolex 24 and the Grand-Am events at Indianapolis and Watkins Glen at which Johnson is also scheduled to drive. A radiothon and live DJ are scheduled to help stoke donations at Daytona.

"Brian is the most down-to-earth person you will ever meet, especially considering his stardom," said DeFoor, who is involved with healthcare banking and lending, "and he said, 'This [driving in the Rolex 24] is an ego thing for me and you, but the [charity] is the right thing. Use me for anything you need to do.'"

Johnson, fellow Rolex 24 rookie DeFoor, former race-winners Elliott Forbes-Robinson and Jim Pace and Carlos de Quesada form an aptly named Fifty-Plus Racing team (all are older than 50) that is working in conjunction with Predator Performance and Alegra Motorsports.

Though Johnson is the latest in a long line of celebrities that have undertaken sports car racing in general and the Rolex 24 in particular, he was a curiosity within the Grand-Am community as word leaked that he would compete. The garage is, after all, filled with men who once had High Voltage cassettes in their hot rods. Johnson has captivated that community with the self-deprecating way he has ingratiated himself to his new peers and his preternatural gifts of connection and storytelling.

Reigning series and Rolex 24 champion Scott Pruett said in a phone interview with SI.com that he, too, was eagerly awaiting his opportunity to introduce himself to one of his musical favorites. Though the Rolex 24 is the signature event of the Grand-Am season, it is a perfectly acceptable venue for newcomers, Pruett said.

"When you look at some of the celebrities in the past who've come out to drive, from Bruce Jenner back with me in the late '80s or Patrick Dempsey and Craig T. Nelson, there's been a lot of celebrities who've come to be a part of our sport," said Pruett, who has four Grand-Am Daytona Prototype championships. "One of the best [races] to come be a part of is the Rolex 24, because as long as you approach it the right way and have the right team around you to keep you grounded, not get excited, once the race gets up and rolling, you can run your own pace, stay out of trouble, run the miles without the stress of a three-hour race or six-hour race where you have to make things happen."

Pruett said he is therefore not concerned about the competency of Johnson or other neophytes dabbling in the most prestigious race of his season. Grand Am, a subsidiary of NASCAR, vets all drivers before they are allowed to compete.

Brian Johnson was born into a drab post-war village of Dunston in the fall of 1947, where life was "coal mine, steel works, ship-build and Newcastle United on a Saturday," he said. He lives most of the year in Sarasota, Fla. -- the rest of the year he spends in London -- but his thick Geordie accent defines him, most evidently when he says the name of his band, "Ehya-C-Deeya-C." He should have been a fifth-generation coal miner, getting as close as an apprentice engineer, but his mother intervened. And from a very young age, there was a love of cars.

"I love the way they look, I love the way they sound," Johnson said, his voice waxing nostalgic. "It's probably because I was born in a small mining village and it's probably because there wasn't many cars there. The doctor had a car, the foreman had a car. The local policeman would have a car, but we lived in government housing and there just wasn't many cars. You might get your odd one but it was all motorbikes and sidecars. Petrol was still rationed and the cars were still ... a lot of them were pre-war cars and just horrible and black. It was dull and turgid."

Everything changed for Johnson in the mid-1950s. England was ascendant again. Hormones and rock and roll and, of course, cars were changing his life.

"Suddenly, in the mid-'50s, there was something," he beamed. "There was the Nash Metropolitan. The first one I ever saw I was like, "Wow, it's two-toned." It just looked different. It was gorgeous. Then the Jowett Javelin, which was stunning. And then cars started turning into these beautiful objects. To me they did, anyway, with these bright colors and blues, and then the Minis.

"England was the king of the world. We had the Beatles, we had the Mini. We still had an army that could fill a football stadium. It was a great time and it was swinging England. And in America, the great thing was, cars and rock and roll came together. The '50s ... watching an Elvis Presley movie, these beautiful Cadillacs, gorgeous, bright red. They were works of art on their own. Of course, they were massive. You couldn't turn a corner in them, but who cares when you have your arm round a beautiful girl, driving down the beach at sunset? It was just stuff my dreams were made of. And it just fed my passion."

Johnson's love of cars was such that when he finally found time to write a memoir, it was a comprehensive tome on all things motoring in his life called Rockers and Rollers. It confused not only booksellers, who didn't know where to shelve it, but fans who turned it into a brisk seller thinking they were about to learn the inside story on Back in Black.

Johnson's car collection is a mix of the nostalgic and the sleek, but he tools around Sarasota in a Rolls-Royce Phantom, odometer approximately 11,000. That's not to say he doesn't get a lot of mileage out of it.

"This one is f------ brilliant," he grinned, referring to the Phantom. "I was telling [Top Gear co-presenter Jeremy] Clarkson about it, because it's his favorite car, too. He says, 'What is it good for, Brian? What was it made for?' and it was him that said, 'I'll tell you what it's for. It's to arrive in.' It was designed to arrive in. And I f------ love it. I love driving it. It's fast. It's quick."

De Quesada learned just how quick the Phantom was during a late-night drive to a test at Sebring International Raceway in November, when his Porsche -- traveling at 120 mph -- was left in a vapor trail among the cattle ranches and groves by Johnson. Johnson and de Quesada met formally for the first time a while later at the track.

"We got a good laugh out of that one," Johnson bellowed.

Though his goals have heightened incrementally as he and DeFoor have pared down lap times under the guidance of their professional teammates, Johnson remains aware of his limitations, joking with DeFoor that perhaps a cross warning should be etched on their rear bumper. But still, they feel a top-five finish is plausible in a 12-team field in the fastest class.

"First of all we were thinking, well, if we can just finish and have a bit of fun, but it's starting to change now," Johnson admitted, sheepishly. "It really is starting to change. ... We've come leaps and bounds. We've knocked about 10 seconds off our time in a day. That's pretty cool. Now it starts to get a steep learning curve, to get that last three to four seconds. We'll never be professionals. We know that. Professional boys go around so fast and make it look so easy ... The last thing they said was don't try to follow them. Don't do that monkey-see, monkey-do s--- or you'll go straight off. These guys know what they're doing. So we're trying not to be heroes and just be sensible and get round the best we can."

But if he errs somewhere in the middle of the night with an innocent little mistake in a curve or out in the fog, he knows his adventure will be dismissed as some metal god's bucket list item gone awry, which would be missing the point. The headlines, though, would be glorious:

For Those About To Wreck, We Salute You?

Shot Down In Flames?

Whole Lotta Slow-sie?

Johnson's cheeks widened at the thought, appreciating the potential humor in his sublime attempt.

"You might yet get to use that one," he cackled. "We're old, but we're spirited."